Saving Henry (14 page)

Authors: Laurie Strongin

As I repeated the conversation with my family and friends that night, it was, of course, not lost on any of us that the Dickey Amendmentâinduced delay that interrupted Dr. Hughes's work for nearly one year had denied us the time for at least three additional PGD attempts.

One of those just might have made all the difference.

⢠Going to Funland

⢠Cotton candy

⢠Winning stuffed animals

⢠Building drip castles

⢠Soft ice cream

⢠Getting buried in the sand

⢠Aunt Alice and Uncle Peter's beach house

F

UNLAND

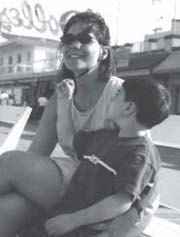

Henry tickles my chin with a magic feather on the boardwalk in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware

The Strongin Goldberg Family

T

he Paratrooper is one of eighteen rides at Funland, an amusement park on the boardwalk in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. The park is filled with music from a vintage carousel, mixed with the sounds of waves crashing, alarms signaling victory in Whac-A-Mole or Skee-Ball, and the laughter and cries of kids and parents overwhelmed with summertime joy. The air is filled with the salty ocean mist and the good, greasy smells of nearby popcorn and

Thrasher's french fries and vinegar. Ride tickets are sold individually for 25 cents, but $10 will buy a book of 54 tickets, and nearly every adult is seen with an abundance of them.

We were barefoot in Funland. It was sunny and warm. We'd had ice cream for lunch and cotton candy for dessert. It was a few days before we were scheduled to leave for Minneapolis, but that didn't matter. Nothing mattered except one sweet fact: Henry and I were on the Paratrooper.

I had ridden the Paratrooper with friends in grade school, boyfriends in college, and Allen as a newlywed. But nothing prepared me for a ride with Henry. It all started with that lookâthat Henry look where his eyes sparkled extra brightly and his double dimples were tempting me to gobble him up.

And then he said, “You know, Mom, if you want to go, I'll go with you.”

Of course I wanted to go. After Henry first made me a mom and I had time to think about all the stuff I wanted to do with him, one of the first things that occurred to me was I couldn't wait to take him to Funland, just like my parents had taken me when I was a kid. I couldn't wait to watch him ring the bell on the fire engine or to ride on the carousel, but most of all, I couldn't wait to ride the Paratrooper with my baby. Of course, with its height requirement, fear factor, and the threat of Fanconi anemia, it was unclear if we would ever get there.

So when he asked the question, I didn't even hesitate. We got lucky and the Paratrooper car that stopped right in front of us was Henry's favorite color: gold. The ride is like a Ferris wheel, but a lot more fun. The seats look like chairs, topped with a big umbrella. We kicked off our shoes and jumped on. The ride began to lift, going faster and faster, and we felt the wind rush through our bare toes and held each other's hands, fingers clasping fingers. As the ride peaked, we screamed as loud as we could. I looked out at

the ocean and breathed and screamed and cried, and wished it would go on forever.

When we neared the bottom, we waved frantically at Allen and Jack. Every time we started our descent, we screamed as if it would never end.

When the ride was over, our cheeks were flushed and Henry's smile was as big as I'd ever seen it. We collected our shoes, and Henry and Jack were off again; darting from ride to ride, stopping for their favorites: the ball pit, the helicopter, the carousel. The tickets in my pocket slowly disappeared.

Then it was time for the games. Henry and Jack picked the game where the main prize was a Pokémon stuffed animal. The object of the game was to throw a beach ball so it would land on the rim of a red or blue bucket, which were surrounded by far too many yellow buckets. One dollar and one try later, Henry won. Arms raised and fist-pumping in victory, Henry selected Charizard, of course. Jack had greater difficulty. The first ball bounced off a bucket and landed on the boardwalk. He tried and tried, to no avail.

“You can do it, Jackie-boy!” Henry yelled while patting Jack's back.

Each loss was met with encouragement by all of us and greater frustration for Jack. Henry asked for another turn and tossed the ball right into the red bucket. Instead of choosing Pikachu or another character, he asked for Blastoise, Jack's favorite. He smiled his Henry smile and handed it to Jack. From the look on Jack's face, that was at least as good as winning it himself.

I wanted this day to last forever, and I felt my disappointment growing as the day grew dark and Allen said it was nearing time to go. But not before we stopped at Kohr Bros. for chocolate-and-vanilla-twist soft ice cream with chocolate jimmies, which Henry and Jack ate while clutching their Pokémons, sitting on a bench overlooking the Atlantic Ocean.

“Can we go to Candy Kitchen?” asked Henry.

“I want LEGO candy and wax bottles!” exclaimed Jack.

“That's what I'm going to get,” Henry added.

As they ran toward the Candy Kitchen, I followed slowly behind, taking in the salt air and what was left of the warm summer sun. In my pocket I found two remaining tickets. I was about to call out to Henry, to ask him what we could get for two tickets, but at the last second, I changed my mind. Instead, I pulled out my wallet and tucked the tickets inside.

Although I knew the road we would travel would be far from easy, somehow I believed it would lead us back to Funland.

⢠Taking pictures

⢠Eskimo and butterfly kisses

⢠Flying kites

⢠Getting out of the hospital

⢠Playing Skee-Ball

⢠Playdates and parties with his cousins

⢠Meeting President Clinton

A

s we readied ourselves for the fight of our lives, my brother, my sister, and the Ladies of the Pines, most of whom I remained close to, were planning for the superhero sendoff party of the century. On the afternoon of June 11, the day after our last Funland trip, and three days before we were leaving for Minnesota, Allen, Henry, Jack, and I walked into Temple Sinai's social hall.

I had heard that there had been a lot of planning involved, but

when I pushed through the doors, I was overwhelmed. There were Batmans everywhere. Not only on the centerpieces and the cake (made especially by one of Henry's favorite people, Max, from our local ice-cream parlor) but standing along the walls, sitting on chairs, and twirling hula hoops on the dance floor. Everyone was dressed as a superhero. Our good friend Mike Rosenberg, a Washington attorney, was dressed as Batman. Michael Barr, who would later go on to work in the White House, was Robin. As soon as they saw Henry and Jack, who were themselves dressed as Batman, they ran to them, lifted them up high above their heads, and flew them around the room. The boys shrieked with excitement and the entire crowd whooped and hollered.

It was an amazing day. More than a hundred family, friends, neighbors, teachers, and doctors came dressed as superheroes as a tribute to Henry and his lifelong obsession. Of course, Bella was there. She didn't have to dress up as a princess to be one in Henry's eyes. Ari, Simon, and Jake came, as did all of Henry's cousins, aunts and uncles, grandparents, school friends, and soccer teammates. His pediatrician was there, as were his teachers Liane, Denis, and Elaine. Henry's classmates presented him with a special Batman pillowcase that they decorated and autographed. Jugglers, magicians, balloon twisters, and plate spinners entertained the kids as they posed for pictures with Batman and Robin, and celebrated the marvels of childhood.

There were gifts for Henry and big hugs all around. My favorite moment, perhaps, was when I saw my dad hand Henry a brand-new shiny silver-and-gold plastic sword. This wasn't just any sword. This was the sword that Henry would carry with him to Minneapolis, to every appointment and every procedure during his first week. I knew this was a big deal, not just for Henry, but for my dad. He is certainly not the type of guy who likes to shop. Rather, he leaves that to my mom, while he is out fishing, flying over Chesapeake

Bay, or relaxing by the fire with a good book. But he had gone alone to the local toy store and picked this one out himself. I knew that it was his way of letting Henry know that regardless of the distance between them, his Papa Sy would be there with him every day, prepared to fight alongside him, and totally ready for battle.

As the evening wound to a close and the younger, wide-awake superheroes were pulled reluctantly toward the parking lot by their older, tired superhero parents, I was filled with joy and gratitude. So many people knew, understood, and loved my son. My brother Andrew came to stand beside me. We watched Henry as he stood with Jack, Bella, Ari, Simon, Jake, and his cousins Michael, Rachel, and Emma, poring through the goodies that had been hidden inside the piñata. They showed one another what they had, and made a few exchanges. He looked so happyâand perfectly healthy. I knew that what was happening on the inside made what we were about to do essential, but that didn't make it any less difficult or confusing.

Andrew put his arm around me. “You know what I think, Laurie?”

“What's that?”

“Batman should wear a

Henry

shirt.”

Â

T

he next morning, Henry announced that he wanted to see Bella one more time before we left for Minnesota. I called Liane and secured a date. Within hours, Bella arrived. She was dressed in a matching flowered tank top and shorts. Henry wore the new Batman Beyond T-shirt that Bella had given him at the superhero celebration the day before. Bella brought a camera with her, which she put to immediate use.

It was hot and sunny, a perfect afternoon for soccer on our front lawn. Bella and Henry teamed up against Jack and his friend Noah.

“Henry, are you the MVP on your soccer team?” Liane asked

after Henry dribbled right by Jack and Noah and scored the first of many goals.

“Yeah, because I eat a lot of food,” Henry replied as he passed the ball to Bella, who dribbled it onto our neighbor's yard and into the bushes for another goal.

Jack and Noah were no match for Henry and Bella, who continued to score on each drive down the eight-foot-long field.

After the game ended, Bella went inside to get her camera. Henry put on his Batman cape for a few final shots.

I gave Liane our address in the hospital's bone-marrow-transplant unit so Bella could keep in touch. As they were preparing to leave, Bella reached into her mom's bag and pulled out a card that she had made for Henry that simply said “Luv, Bella.” Inside the card were two small, soft M&M's figures, one blue, the other green. Compliments of two small pieces of velcro, they were holding hands.

“Look, Mom! Look what Bella gave me!” Henry exclaimed. He ran over to me and whispered something in my ear. It was important.

“I want to give Bella a hug,” he explained.

“I think she'd like that,” I whispered back.

He inched away from me and toward her. Liane saw what was going on and gently pushed Bella Henry's way.

Henry and Bella embraced. For the last time that year.

Â

T

he night before we left for Minneapolis, Henry and Jack became taken with fireflies. Their interest was sudden and overwhelming, and they spent a great deal of time running around our front yard, catching one firefly after another. Each catch was a victory for my sons, though not for the bugs, many of whom gave their lives in the clumsy, innocent hands of my three- and four-year-old boys.

As I was watching them that evening from the swing on our front porch, I let my mind drift to thoughts of my own childhood, of the

curiosity and wonder about the world that defines a child's dreams. When I shook myself from my reverie, I noticed that Henry had disappeared inside the house. Inside, I didn't see him on the first floor, and so I went upstairs. I slowly opened his bedroom door.

“Mom, come in quick,” I heard in an insistent whisper. “Close the door.”

The room was dark. And then I saw them: dozens of pinpricks of warm, yellow light, flashing and floating above Henry's head. He had carried the fireflies upstairs, one by one, cupped in his hands. Then he set them free.

“It looks like the sky,” he whispered, reaching over to take my hand. He was the picture of joy, lying on his back, watching the fireflies light up his room.

It was this image of Henry that would carry me through some of the darker moments during our time in Minneapolis.

Â

T

he next day, Allen, Henry, and Jack were in the car. The trunk was packed, the ignition was on, and they were waiting. I was still inside. I had turned off the lights, closed the blinds, and checked, yet again, to be sure all the appliances were unplugged. Flipping off the last light, I stepped onto the porch and began to pull the door closed. But instead, I paused. I went back inside, back upstairs, and stood in front of the door to Henry's bedroom.

HENRY

.

I traced the letters on the door, the ones that had been there since he'd moved into this room, this house, our lives. I opened the door and walked in and, in the quiet, I looked around. In the closet, his costumes: Batman, Buzz Lightyear, Peter Pan, an astronaut. Under the bed: a couple of stray Batman toys, typical kid stuff. I could find nothing among his toys, his soccer cleats, or his books that justified our trip to Minneapolis. I could still see nothing in his face or smile

or boundless energy that convinced me that we were doing what needed to be done. For that, I would have to study the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund's scientific updates predicting improved bone-marrow-transplant outcomes, read through our thick file of the results of his blood tests, and look at my still-bruised thighs.

We are doing the right thing.

I repeated these words silently to myself as I walked back downstairs. Moving forward with Henry's bone-marrow transplant while he was still strong gave him a better chance of returning to his room and his life than waiting longer or not having a transplant at all, which on all accounts would be met with certain death.

We are doing the right thing.

I stepped onto the porch and locked the door. I had done this a million times, of course, but this time was different. I was unsure if Henry would ever step foot in the house again, or if I would ever want to. I climbed into the front seat next to Allen and turned around to Henry and Jack. “You ready for this adventure?” I asked.

“Yeah!” said Jack.

“Yeah,” repeated Henry. “Off we go!”

As we began the eighteen-hour trip to Minneapolis, driving east on Calvert Street, north on Wisconsin Avenue, and out of DC, Allen took a CD from the stack:

Henry's Mix

. He slipped it into the CD player and with each new song, my mind was flooded with memories.

When Henry was three, we bought him his first boxed set, the four-volume

Nutshell Library

by Maurice Sendak, and the CD that accompanied it, Carole King's

Really Rosie

. Bedtime featured “Pierre” Henry's favorite from the set. It was also, therefore, song one on

Henry's Mix

. Allen and I would lie in Henry's bed, singing the story with Henry as he turned the pages. We would all yell, “I don't care!” as loud as we could along with Pierre and Carole. Long after we hugged him good night, exchanged butterfly kisses with a flutter of our eyelashes on one another's cheeks, and left his room,

we would hear Henry shouting, “I don't care!” until there was silence. As I recalled that wonderful bedtime ritual, on cue, Henry and Jack yelled from the backseat: “I don't care!” Their timing was perfect.

Tom Chapin's “Homemade Lemonade” was next. Henry's friend Simon introduced Henry to this song on the way home from a play date. It is an ode to the tasty superiority of the fresh squeezed, straight-from-trees variety and the financial return associated with one of childhood's biggest pleasures, the lemonade stand. I thought about Henry's first lemonade stand, which he managed with the help of Jack and his friend Jacob, and which featured a homemade lemonade blend and fresh-from-the-oven chocolate chip cookies. Advertised at 25 cents per cup and per cookie, the boys often got paid more. Over the years, I have noticed that there seems to be a correlation between the number of letters written backwards on lemonade-stand signs and overpayment for the product. The elder of the crowd and originator of the idea, four-year-old Henry manned the table while Jack and Jacob ran up and down our street recruiting customers. “Lemonade for twenty-five cents⦠or if you don't have any money, it's free!” yelled Jack. A couple of hours later, the kids had divided up all the money (Jack was not penalized for his socialist ways) and we celebrated their commercial success with ice-cream cones at Max's.

Next: Todd Snider's “Beer Run.” And yes, on a four-year-old's mix. We easily rationalized the content by the fact that it was also a spelling lesson, which clearly had worked. From the back seat, our two young sons loudly sang along with Allen and me: “B double-E double-R U-N beer run. B double-E double-R U-N beer run. All we need is a ten and fiver, a car and key and a sober driver. B double-E double-R U-N beer run.”

Henry's CD also featured songs like “Krusty Krab Pizza” and “Ripped Pants” featured on

SpongeBob Squarepants,

and “If I Had

a Million Dollars” by the Barenaked Ladies because Henry thought they were funny. He liked “Brick House” by the Commodores, “Out of Habit” by BR-549, and Smash Mouth's “All Star” because he could sing them while swinging his hips and dancing, which didn't work so well while he was belted into his car seat. He liked the songs written especially for him like “Henry, You're Our Superhero” by Caron Dale, the music teacher at his preschool because⦠well, they were about him.

While Jack and Henry sang along in the backseat, up front, I struggled to make sense of our recent experience. We gave it all we had. We worked with the world's best doctors. We hoped. We believed. We were brave. We persevered. And despite all that, it didn't work.

In the end, I am left with my belief system intact. I believe in love and science. Nothing more, nothing less.