Saving Henry (15 page)

Authors: Laurie Strongin

⢠The Mall of America

⢠Camp Snoopy

⢠Rock climbing

⢠His shiny silver Nike sneakers

⢠Roller coasters

⢠Collecting marbles

⢠Sleeping in hotels

W

e had spent four years raising money for the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund, organizing bone-marrow drives that attracted hundreds of willing donors, and waiting for science to produce better drugs, better treatment protocols, improved bone-marrow-transplant success rates, and gene therapy advances. While our previous searches of the National Bone Marrow Registry initially produced eleven perfect matches to Henry, more in-depth testing

showed that, of those, the best we had was merely one five-out-of-six HLA mismatched, unrelated donor.

In all likelihood, Henry's donor, like so many others on the registry, had responded to a friend's or neighbor's call for help. Ironically, in the early 1990s, long before I was pregnant with Henry, I had heard about a local woman named Allison Atlas and her need for a bone-marrow donor to cure her leukemia. When I went to get tested, a woman came up to me and said that my resemblance to Allison was striking, and that I was sure to be the perfect match. How I hoped it would be so. Sadly, I wasn't a match for Allison, who died tragically young, despite the more than 90,000 donors the organization Friends of Allison has added to the registry.

Having been told by child life specialists that it would be a good idea to talk with Henry about the purpose of our trip to Minnesota a few days before we arrived, I took the opportunity to do so when we stopped in suburban Cleveland to visit our friends Karen and Chip Chaikin along the way. I walked along as Henry, Jack, and their friend Sam Chaikin enthusiastically chased wild rabbits up and down the block. As was usually the case, Henry was the last to tire, so, when the others had had enough, he ran to my side and begged me to join him. I saw a chance to have the difficult, but necessary, talk.

I was holding his hand, searching for bunnies. “Henry,” I said, “you know how we're going to Minneapolis to see the doctor?”

He nodded.

“We're going because your blood isn't working right so we are going to get you new blood.”

“I know. We already talked about that,” he said.

I continued, “We have to give you a bunch of medicine that might make you feel sick. Your hair might even fall out, and you are going to have to wear a mask for a long time. It will kind of be like Michael Jordan and Batman combined.” I paused, trying to sense if

the information I was sharing was scaring him. “All of the medicine will help the new blood find a good home in your body. It will make you all better so you can go back home and play soccer with the Dolphins and see Bella more, and the doctors a lot less.” Henry listened. I stopped walking and kneeled down in front of him. “Henry, do you want to talk about anything? Do you have any questions?”

“Yeah, Mom,” he said, his eyes searching the surrounding front lawns. “Where do you think that bunny went?”

Â

W

hen I look at photographs from our trip to Minnesota, we resembled a family heading out for spring break, having a great time. There are pictures of us at the Nike store in downtown Chicago, where Henry acquired his favorite Michael Jordan number 23 Chicago Bulls basketball jersey and sweatsuit, and in the process, ran into our own DC United soccer team. There's us having lunch and playing soccer on the shores of Lake Mendota at the University of Wisconsin. While the kids slept in the backseat, Allen and I didn't talk about the things underneathâour fears, our desperation. Instead, we talked about the things we always talked about when we took road trips: where it would be fun to stop along the way, music and musicians we liked, our family and friends, current events.

Within an hour of arriving in Minneapolis, we checked into our temporary housing, a hotel that served as overflow for the far more desirable Ronald McDonald House, which had more sick kids and families than it could hold. For years, I had been dropping extra change into the Ronald McDonald House collection box by the McDonald's cash registers in the hope that in some small way it would help those sick children get better. It was nearly impossible to fathom that my son would be one of those sick kids and that my family would benefit from the $3.49 Happy Meal that left 51 cents to help out people like us. We joined the Ronald McDonald House

waiting list, hoping that someone would get better and get to go home so we could move in. At the time it didn't occur to me that sometimes families check out never to see their child again. Ever.

Henry and Jack loved staying in hotels: playing video games on the TVs, ordering room service, pushing all the buttons on the elevators. If there is a game room, forget it. They would be lost for hours. But this hotel was different. For one, we were on the ground floor, so there were no buttons to press to get to our room. There was no room service. No games on the TV or anywhere else. Our view was a parking lot. Our destination: a children's hospital.

Soon after we arrived, we put our bags in the dark and dismal room and headed out in search of some fun. I needed an immediate escape from the fear that threatened my ability to enjoy our last day together, for who knew how many weeks. As good fortune would have it, the country's biggest, brightest, busiest, noisiest, happiest place was a mere fifteen minutes away. Mall of America boasts 4.2 million square feet of retail therapy, which for me and my family was a start.

Mall of America has something for everyone. Groups of elderly people in Easy Spirit shoes walk the half-mile-plus indoor linoleum “track” on each level for exercise. Couples tie the knot in the Chapel of Love. If you can't find what you want or need in the more than 520 stores, then it probably doesn't exist. We logged eight hours in that first trip to the mall.

Jack's first choice, and therefore one of our early destinations, was the Underwater Adventures Aquarium, the world's largest underground aquarium. Jack had always been fascinated by animals, particularly those that live underwater. By that time, he had already amassed a huge collection of plastic whales, which he would line up and categorize by tooth type (baleen vs. toothed) and then again by ocean habitat. (He would later, at age seven, be invited to teach a kindergarten class on whales and dolphins.) At the aquarium, Jack

darted from tank to tank, pointing out all the different types of fish. Henry chased after him. After seeing what seemed like thousands of sea creatures (4,500, if the advertisements are right), the boys arrived at the shark tank, where they had the opportunity to touch real live sharks and stingrays. As Jack explained the familial relationship between sharks and rays, Henry reached right in to touch a stingray. As Henry's hand hit the water, a shark reared its head, exposing its sharp teeth (at least this is how the boys tell it) and darted toward Henry. Jack saw it all happen, grabbed Henry, and pulled his arm out of the water. In that moment, the story about how Henry nearly got eaten by a sharkâand about how Jack saved himâwas born.

All that excitement made us hungry, so we headed to the Rain-forest Café. With its cute animals and very full and colorful gift shop, Henry was in his element. Up until the faux lightning and thunderstorm, Jack liked it too. But with the first clap of thunder, Jack bolted out of his seat and ran as fast as he could out of the restaurant. Allen ran after him, but could not convince Jack to return. Jack waited outside, far from the thunder, while Allen informed me that Jack had accepted his offer to go to the mall's LEGO store, but refused to come back in to finish his lunch. Henry and I finished up our meals and got Jack's pizza and Allen's burger to go. Thankfully, the LEGO Imagination Center was on the same level, so we met Allen and Jack, the latter of whom was busy constructing LEGO cars to send down the ramps. Jack could have spent hours checking out the huge LEGO dinosaurs, and building and racing LEGO cars in the build-it-yourself bins. And, over time, he did.

Amazingly, right in the middle of the mall is Camp Snoopy, a seven-acre amusement park with rides, games, and junk food (also known in our family as breakfast, lunch, and dinner). We rode the Li'l Shaver roller coaster many times, raced boats, and ate ice cream.

Without the Boardwalk and Atlantic Ocean, it was no competi

tion for Funland, but it was big and loud and fun and Henry-ish, nevertheless.

Â

I

had tried to prepare myself for the moment when we had to walk into University of Minnesota's pediatric bone-marrow-transplant clinic. But when the four of us finally pushed through the wooden doors at 8 a.m. the next day, and I saw the rows of chairs filled with little kids wearing baseball caps to cover bald heads, their faces swollen from steroids and absent of smiles, I had to fight the urge to grab Henry and Jack and run back to the car. We didn't belong here in the land of the sick, where how people were doing was so obvious it was pointless to ask.

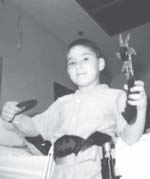

For the first five days, Allen and I had meetings: Henry's radiation therapists, his cardiologists, nuclear medicine technicians, social workers, infectious disease specialists, and, because radiation and chemo cause tooth decay, even dentists. Henry, meanwhile, endured numerous blood tests, IVs and anesthesia, a bone-marrow biopsy and aspiration, chest X-rays, an echocardiogram, kidney and liver ultra-sounds, chest and sinus CAT scans, and dental X-rays. He attended a radiation-therapy consultation, radiation simulation, and a bone-marrow-transplant class, where he was offered the opportunity to play with a bald doll with a central line in his chest. Needless to say, it was no competition for the Batman figurine he brought with him.

He remained upbeat throughout it all, carrying to each appointment the sword that Papa Sy had given him. As the nurses prepared to take yet another sample of blood or insert an IV, Henry would hold that sword tight, stick it high in the air, and exclaim, “Let's get it over with and get out of here!” The nurses would burst into giggles and have to take a moment to compose themselves before inserting the needle.

Watching Henry approach these experiencesâeven a trip into the small, dark MRI machineâwith courage and a sense of humor not only made me appreciate my son for his ability to make everything better for everyone else, but it also provided Allen and me with the strength we needed to keep signing medical release forms. And checking yet another day off the calendar. Each afternoon when the assortment of tests and procedures was over, we left the hospital and headed for something, anything, that better resembled the life we had left behind at home.

One afternoon Allen took Henry and Jack to a party in the hospital courtyard so they could meet some of the Minnesota Vikings cheerleaders and cheer for their favorite turtles during the hospital's annual Turtle Derby. I stayed in the hospital clinic to talk with the child life specialist, hoping to better understand what to expect over the next days, weeks, and months. I had spent hours and hours on the Internet searching and re-searching the Centers for Disease Control, and every other website I could find, to help prepare Henry and our family for the transplant. While there was plenty of information on the stages of the transplant process and how Henry's body would react, I still didn't know much of the critical stuff. Whether Henry could bring the blanket my mom knit for him when he was a baby into his hospital isolation room. How many weeks or months Jack would have to wait to see him. Or whether I could kiss or hold Henry.

I longed for a rule book that we could follow to guarantee that Henry would survive, but none existed.

⢠Tae Kwon Do with Anthony, Vijay, and Mr. Kim

⢠The Magic Closet

⢠Walkie-talkies

⢠Wrestling with Jack

⢠Playing bingo

⢠Eating brownie batter

⢠Linus Van Pelt's sage advice, “Never jump into a pile of leaves with a wet sucker.”

I

t was hard being in Minneapolis, doing what we were doing, absent everything that provided comfort in our lifeâour friends and family, our school and jobs, our neighborhood. Our home. Everything was foreign. Initially, we spent lots of time trying to establish routines to create some semblance of normalcy. Allen and I had both secured leaves of absence from our jobs, thanks to the Family and Medical Leave Act, so we could focus every effort on

getting Jack and Henry settled in Minneapolis for a four-month stay, and on Henry's recovery. My mom stayed with us for nearly the entire time. I don't know if we asked her to come or if she offered, but we needed her to be with us, and she needed to be there. She sacrificed time with my father, my sister and brother, and her other grandchildren, not because she loved us more, but because she loved us. She saw agonizing things that no grandmother should see, but Henry loved that she was there every day. Having lost her own mother as a young girl of fifteen, my mom knew to appreciate the gift of time with someone you love.

Through a medical insurance benefit that provided a generous housing allowance, we were able to rent a lovely, newly refurbished, two-bedroom apartment in the historic Calhoun Beach Club on the north shore of Lake Calhoun, one of Minnesota's 10,000 lakes. I was initially hesitant to select an apartment that was nicer and more expensive than our home in DC, and in such stark contrast to the cheerless purpose for being there, but Allen and my sister Abby, who had flown in from Washington to help us get settled, convinced me that weâand Jack in particularâwould benefit from a private, comfortable, and peaceful place to live amidst the disorder of our lives. This home-away-from-home was just ten minutes from the hospital and provided easy access to parks, swimming pools, summer camp for Jack, and the peace and beauty of the lake.

In addition to my mom and Abby, so many members of our family flew to Minneapolis to be with us for welcomed stretches of time. Cousin Hannah, Aunt Jen, and Uncle Dan came, and accompanied Jack and Henry to the Children's Museum and on the Li'l Shaver roller coaster in Camp Snoopy. The boys fished at Lake Harriet with Papa Sy. They watched fireworks with cousins Emma and Sam, and Uncle Andrew and Aunt Tracey.

It helped so much having them with us, giving us all something to look forward to after finishing up Henry's medical appointments.

Each day of our first ten days in Minneapolisâwhen Henry was still an outpatient, and allowed to come home with us in the eveningsâwe checked additional medical tests off the list and learned a little more about how to balance Henry's medical needs with the fact that he was still the vibrant, funny boy he had been long before they affixed the

HENRY GOLDBERG

,

DOB

10/25/1995 plastic band to his wrist. Despite everything, Henry still didn't think of himself as being sick. He was always just getting better. Convinced of the connection between good attitudes and good outcomes, we were determined to keep it that way. We brought our own portable DVD player to the hospital waiting and treatment rooms so that the boys could stay entertainedâlaughing and reciting lines from their favorite moviesâright up until anesthesia was inserted into Henry's IV and he fell asleep. When he woke up, we resumed the movie or played his favorite music or walked to the vending machine armed with loads of quarters for Pringles and M&M's.

At the end of each day, we'd all gather back at the house for takeout dinners and games, or we'd go out for ice cream or to the movies. While the adults were, of course, well aware of what was at stake, none of us talked about it. What was the point? We had chosen the only real choice we had, and the only place to go was forward.

Â

D

ay 0.

This was how Henry's doctors referred to July 6, the day of the transplant: the day on which Henry's life would begin anew. Seven days prior to this, on June 29, Henry was admitted as an inpatient on the bone-marrow-transplant unit, and we passed the point of no return. Soon after Henry was settled into his new room, he was sent down for surgery, where a doctor inserted a central venous catheter into a large vein in Henry's chest just above his heart. This would enable doctors and nurses to administer drugs and blood products

painlessly, and to withdraw hundreds of blood samples without continuously inserting needles into Henry's arms or hands.

On Day minus 6, Henry, covered in temporary Pokémon tattoos, held his blanket and smiled as he was strapped to a table and submitted to total body irradiation while listening to and singing along with his favorite Disney music, including “Heigh-Ho,” “The Bare Necessities,” and “I Just Can't Wait to Be King.” The radiation therapist, intent on doing his very precise job, had to remind Henry to sit still and resist the urge to move to the beat of the music. Day minus 5, minus 4, minus 3, and minus 2 featured chemotherapy, which worked in concert with the radiation to destroy Henry's existing bone-marrow cells and to make room for the new marrow. Day minus 1 was a day off, and we watched movies in his room.

Allen and I, meanwhile, had enrolled in a total-immersion course in an entirely new language: cyclophosphamide, anti-thymocyte globulin, cyclosporine, heparin, and bilirubin. We went from signing consent forms for preschool field trips to the zoo to those allowing doctors to give Henry drugs that could cause nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, bleeding, liver damage, learning disabilities, infertility, and difficulty breathing. Most of these side effects are, unlike death, temporary and reversible, so we stayed focused on our ultimate goal and signed the forms.

The colorless, quiet, sanitized, isolated hospital room was a shocking difference from where we had been just two weeks earlier: school, Funland, a Dolphins soccer game, and a huge, crowded going-away superhero extravaganza. Instead of the sounds of kids laughing or screaming with delight, the only noise was the constant swishing and beeping of Henry's IV pump or the squeaking of the nurses' shoes. Instead of colorful classroom walls featuring kids' artwork or Henry's bedroom filled with soccer trophies and Pokémon posters, the hospital room walls were white and bare. Replacing the scent of fresh popcorn or cookies or cut grass was the

antiseptic smell of clean. We had traded everything for almost nothing at all.

Initially the really bad times were few and far between, and we did our best to create an upbeat environment for Henry in Room 5 of Unit 4A, where he would remain for a minimum of one month in nearly total isolationâan eternity to a four-year-old. One of the first things we did was to decorate the outside of his hospital room door with pictures of Henry in his Batman costume, Henry with Jack, Henry with Bella, and a photo of our family at the beach, to show the doctors, nurses, and technicians who was living on the other side. Inside, we managed to turn Henry's room into a playroom for one, featuring a blow-up Batman chair, basketball hoop, soccer goal taped to the door, and Pokémon and Michael Jordan posters.

On one of the first days, Henry received an urgent letter. It was from our neighbors in Washington, and it read, “Hey, Batman! Calvert Street misses you and needs your help! The evil villains Catwoman and the Joker have attacked our small neighborhood. We will try our best to hold them off while you undergo your top-secret transformation. We miss you and your trusty sidekick Robin, and hope you come back soon!”

Henry also received a letter from President Clinton, who wrote: “I recently heard that you are going through a difficult time, and I want you to know I'm thinking of you. I'm impressed by the courage you've shown in facing such a tough personal challenge.”

Though we were sure that Henry had what it took to win the battle, Allen decided to take one particular caution, just in case. On the second day there, Henry woke up to find a huge black-and-yellow Bat Signal painted on his window, letting his hero know that Henry could use some help.

“Wow!” Henry yelled as he carefully pulled the IV pump to which he was attached closer to the window to get a better look. “That's so cool!”

Henry took everything in stride, managing, somehow, to find the cheer in his experience. When his hair fell out, he looked in the mirror, smiled, and exclaimed, “Awesome! I look like Michael Jordan.” It was far less easy for me. I had always taken solace in the fact that he looked so “normal” and healthy. That made Allen and me less scared about the idea that “underneath,” he was really sick. As I looked at him rubbing his bald head in the mirror, I smiled and told him he was right. He did look cool. And handsome. But inside, I was in knots. I'd rather have avoided that truth.

Thanks to my brother Andrew and his family, though, Henry quickly had a whole complement of cool hats and bandanas to wear. And thanks to Jason, the hospital unit's child life specialist, a bright blue-and-green Franklin punching bag with the word “Pow!” printed on it hung directly above Henry's bed. As yet another day's worth of chemotherapy dripped from the IV bag through the plastic tubing and into his body, Henry donned his two bright red boxing gloves, each of which repeated “Pow!” held one fist in the air, and exclaimed Muhammad Aliâstyle, “I am the Greatest!”

Â

T

he night before Henry's bone-marrow transplant, Day minus 1, I sat in his hospital room, unable to sleep, reading magazines that don't challenge the mind to do more than pass time. In one, I noticed Martha Stewart's calendar. Her job that day, Thursday, July 6, 2000, was to “clean freezer and refrigerator.” On Henry's calendar that day, the word “transplant” appeared. Just one word with so much potential. Somewhere in the world, our donor's calendar read something equally meaningful. How I longed to spend a day, even an hour, inspecting the “use-by” dates on the food in our refrigerator.

Transplant day was considered Day 0. The hope was that by Day 21, the new bone marrow would engraft (this is when the bone marrow starts to produce new, healthy white blood cells, red blood

cells and platelets), and Henry and his immune system would be on the road to recovery. Day 100âa critical milestone in the world of bone-marrow-transplant patientsâseemed like a lifetime and a dream away. On Day 100, if we were among the lucky few, I figured we would go into the hospital and the doctor would remove Henry's central line, discontinue all his medicines, and send us back home. It would mean that for the first time in his life, my son would be out of grave danger.

The stem cells for Henry's transplant came compliments of a total stranger, and they arrived in Henry's room shortly after eight p.m., nearly five hours ahead of schedule. Allen was at the apartment with Jack, and so the moment belonged to me, Henry, and the stem cells of a woman I didn't even know. I wondered where she lived, if she was Jewish, if she looked like me. All I knew was that the donor was a woman, a kind and generous woman somewhere in the world, who had the ability to undo the damage that Allen's and my genes had wreaked on Henry. Earlier that morning, I had been obsessively checking the weather conditions in Minneapolis and every major city in the country, terrified that the stem cells would be diverted or destroyed on a plane. But the doctors confidently assured me that they would arrive safely, something they knew to be true because, unbeknownst to us at the time, Henry's donor was a nurse from Minnesota. She was donating her stem cells for Henry in a room just down the hall. According to the rules of the National Marrow Donor Program, both her identity and Henry's would be kept confidential, although we couldâand didâcommunicate by letter through our donor-search coordinator. If both parties consented, we could meet following the one-year transplant anniversary.

From 8:15 to 8:30 p.m. Central Time, I lay down next to Henry in his hospital bed and held him, careful that my hug wouldn't interfere with the IV line pumping the stem cells, and a world of possibility, into him.

“Henry, remember how I told you about your new blood?”

“Yes.”

“Well this is it,” I told him.

“Great,” he said, opening a Nestlé chocolate Wonder Ball and reaching to the bedside table. “Want to have a Pokémon battle?”

He grabbed Charizard and I grabbed Pikachu.

“Charizard, I choose you,” said Henry.

“Pikachu, I choose you,” I replied on cue.

“And with a fire spin, a growl, and then the powerful flame thrower, Charizard wins the battle,” Henry said as the stem cells flowed into his body. From there, they had one single, critical purpose: to find their way to Henry's bone marrow, where they'd establish a home and start to produce new blood cells.

I had been told these fifteen minutes would be uneventful. They were anything but. As I lay there next to Henry, I thought, again, about the one thing that had been plaguing me since his diagnosis: We had given him Fanconi anemia. While I never

blamed

myself or Allen, or either of our mothers, who had passed it on to us, I believed that PGD would enable us to take it away. We tried everything to make that possible. But at the moment of the transplant, as I held my son while a stranger's stem cells dripped slowly into his body, I felt at peace. For the first time since I had heard the words “Fanconi anemia,” I relinquished control, accepting that it was now out of my and Allen's hands. I held Henry tightly to me, believing it would all work out. Knowing that Henry could survive.