Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women (22 page)

Read Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mahon

Tags: #General, #History, #Women, #Social Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women's Studies

During her lifetime, Ida constantly struggled between her militancy and her need to be perceived as a “lady.” Her inability to work successfully with groups meant that she was alienated from movements she founded and she failed to get appropriate credit for her work during her lifetime. For decades after her death, her achievements went largely unsung. It is only in the last forty years that she has gotten the recognition she deserves. In 1990, a U.S. postage stamp was issued, and her work is now studied and taught in high schools and colleges. In 2005, her work was lauded on the floor of the U.S. Congress.

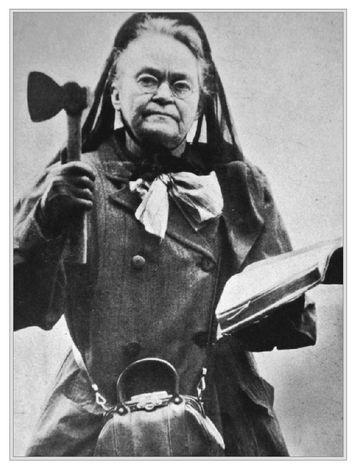

Truly does the saloon make a woman bare of all things.

—CARRY NATION

Both repellent and fascinating, this hatchet-swinging, Bible-thumping, God-appointed vigilante swung through Midwestern saloons, smashing glass with shrieks of triumph, like an early-twentieth-century “Dirty Harriet.” This self-proclaimed “bull-dog running along at the feet of Jesus” objected not just to drink but also to smoking, the Masons, risqué art, and ostentatious fashion. She took particular delight in assailing people and institutions; not even the office of the President was safe from Carry Nation. Her detractors considered her to be a puritanical killjoy, while her supporters considered her to be a second John Brown. “Savage” and “unsexed” were just some of the words used to describe this grandmotherly woman who stood almost six feet tall. But for Carry Nation, the crusade was intensely personal. She’d seen up close the damage that drink could do.

Carry was born Carrie Amelia Moore in 1846 in Kentucky to a prosperous family. Her mother, frequently ill from constant pregnancies and the strain of taking care of her four older stepchildren, alternated between violent antipathy toward her and smothering her with affection. As a child Carry slept in the slave quarters rather than in the big house with her parents. It was there she found the affection that was lacking from her mother. Young Carry was fascinated by the slaves’ attitude toward religion, their songs and shoutings, and their belief in spirit possession. She kept the secret of their slave meetings, and they rarely tattled on her for her childhood indiscretions.

Carry was a semi-invalid through most of her childhood, suffering from chlorosis, an iron deficiency that manifested a greenish skin color. Biographer Fran Grace believes that Carry’s invalidism might also have been her way of rebelling against being forced to give up her tomboyish ways to conform to society and her mother’s expectations of appropriate female behavior. Being sick kept her from having to assume any responsibility around the house.

The Moore fortunes declined and Carry and her family moved several times, from Kentucky to Missouri and then to Texas. When the Civil War broke out, they had to leave their slaves behind in Texas, while they moved to Independence, Missouri. With no slaves and her mother sick, Carry was forced to take over the household.

When she was eighteen, she met Dr. Charles Gloyd, a Civil War vet who was boarding with her family. Starved of affection, Carry was susceptible to his attentions. Totally innocent, when he kissed her for the first time, she thought she was ruined. But her parents disapproved; not only couldn’t he support her, but they also figured out he was a drunk. Forbidden to speak, Carry and he exchanged letters by hiding them in a volume of Shakespeare.

Eventually her parents relented. Even on their wedding day, the groom couldn’t stay sober, swaying at the altar as he said his vows.

The marriage was a failure; Gloyd preferred drinking with his buddies to spending time with his wife. Carry would often stand outside the Masonic Hall pleading for him to come home. After six months, Carry’s family persuaded her to leave Gloyd and come home. Carry begged Gloyd to sign the temperance pledge but he refused. Their daughter, Charlien, was born in the fall of 1868. When Carry came to retrieve her belongings, Gloyd begged her to stay, predicting his death if she didn’t. He drank himself to death a few months later. Carry was now a widow at twenty-two, with a baby to support. She regretted for the rest of her life that she had left him, believing that she could have saved him if she’d stayed.

Devastated, Carry decided to strike out on her own. She sold her husband’s books and medical equipment and moved to Holden, Missouri. There she lived with her child and mother-in-law. Earning a teaching certificate, she taught for four years until she got into a dispute with a school board official. With no way to support herself, Carry decided her only other option was to marry again. Her second choice was no better than her first. David Nation was an old acquaintance, a lawyer, journalist, and parttime preacher. He was also a recent widower nineteen years her senior with five children. They married three months after his first wife’s death. It was a marriage of convenience; his kids needed a mother, and she was jobless and broke. Three years after the marriage, they moved to Texas to grow cotton, with little success. While her husband struggled to establish himself, Carry became increasingly independent over the years, running two hotels and finally acquiring a degree in osteopathic medicine.

A deeply religious woman, Carry began to have visions and dreams during this period. She felt that she was baptized with the Holy Spirit. In church, she began to break in on the sermons, bursting into prayer or song, and she took to contradicting the preacher when he spoke. Like Anne Hutchinson, she came into conflict with church elders who were dismayed that a woman could suggest that it was possible to have a direct line to God. She was eventually expelled from the church. Although as a child she’d been baptized in the Christian church (Disciples of Christ), she no longer subscribed to one particular creed. Her religious fervor came from a grab bag of influences that she stitched together like a patchwork quilt. It encompassed slave religion, Roman Catholicism, and a few tenets from the Baptist and Methodist churches.

Living in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, Carry became active in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and served as a “jail evangelist” to drunks in jail to try to show them a new way. What stuck in her craw was that many saloons in Kansas sold liquor in violation of the state’s prohibition law,

15

and oftentimes legislators and law enforcement officers looked the other way or participated in the illegal activity themselves.

15

and oftentimes legislators and law enforcement officers looked the other way or participated in the illegal activity themselves.

In 1900, she became president of the county WCTU. Realizing that writing letters to legislators wasn’t doing any good in getting the prohibition law enforced, Carry decided to take matters into her own hands. Carry called on the governor’s mansion and reamed him out big-time for not enforcing the law in his own state. She prayed to God for direction and claimed a vision came to her that told her to go to the town of Kiowa. So she took her horse and buggy and headed to Kiowa, armed with bricks to destroy the saloons there. Soon she switched to a hatchet, which was more practical.

Alone or accompanied by hymn-singing women from the WCTU, she would march into a bar and, singing and praying, smash up the bar fixtures and stock. Early on, saloons hired plants and undercover policemen to try to infiltrate the meetings of the “Nation Brigade.” To get around this, brigade members used special code words for entry and wore white ribbons. Moving on to Wichita, she wrecked the bar at the Carey Hotel, one of the most luxurious in the Midwest, causing three thousand dollars’ worth of damages. She spent two weeks in jail but was undeterred. Soon Topeka and Kansas City also felt the fury of her hatchet.

Although Nation believed that her mission was from God, it was still dangerous. She was pushed down, threatened with a gun, beaten and whipped by prostitutes, pelted with rocks and raw eggs. One saloon owner’s wife punched her in the face. Over the course of her career, she was jailed over thirty times, from California to Maine. Even in jail, she was subject to abuse. In Wichita, the judge issued quarantine in the jail, and she was thrown into solitary confinement for days at a time. On more than one occasion, Nation was pursued by a lynch mob. Carry, however, was fully prepared to be a martyr to the cause. In 1901, the state temperance league awarded her a gold medal and the title of “bravest woman in Kansas.”

Carry’s antics, or “hatchetation,” as she liked to call it, made her a nationally known figure. Newspapers eagerly covered her day-to-day activities. Nation was soon receiving two hundred letters a week. Meanwhile her husband divorced her for cruelty and desertion. After the decree came through she said, “Had I married a man I could love, God could never have used me.” Although a divorce tarnished her reputation as a “defender of the home,” Nation now decided that social reform demanded that women see the world as their home. Along the lines of the Salvation Army, Nation organized the Home Defenders Army, creating hatchet brigades. She even tried to reach out to children and teenagers. Despite her reputation as a harridan with a hatchet, Carry was generous to a fault. She collected clothes for the poor and invited them to her house for Thanksgiving and Christmas.

In response to her crusade, saloon owners began to offer “Carry Nation” cocktails while the Senate Bar in Topeka, after reopening, offered a relic from its smashing with every drink. Business boomed so much that the bar had to hire four more bartenders. “All Nations Welcome but Carry” became a popular slogan in bars. After a merchant gave her some pewter hatchet pins left over from Washington’s birthday to sell to pay her legal fees, Nation had her own emblazoned with “Carry Nation Joint Smasher.” They became collector’s items; people who didn’t even believe in her crusade had to have one. Media savvy, she also hawked autographed photos, buttons, her autobiography, and even special water bottles.

In 1903, she had her name legally changed to Carry A. Nation since she believed that was what God had chosen her to do. Carry took her message to the state capitols, not waiting for an invitation to the legislatures of Kansas and California. She once caused the U.S. Senate to grind to a halt while she was forcibly removed from the public galleries for having shouted out her opinions. She started several short-lived magazines with catchy titles like

The Smasher’s Mail

and

The Hatchet

. All the money that she made went to serve her causes, the magazines, and homes for the families left behind in poverty by alcoholism.

The Smasher’s Mail

and

The Hatchet

. All the money that she made went to serve her causes, the magazines, and homes for the families left behind in poverty by alcoholism.

For the next several years until her death, Carry Nation traveled nationally and internationally, from lecture halls and college campuses to the vaudeville stage. Carry believed that God had called her to take her message to the stage, to reach the masses. “I am fishing. I go where the fish are, for they do not come to me. I found the theaters stocked with the boys of our country. They are not found in churches.”

People either liked her or didn’t but no one was indifferent to her. She made no apologies for her religious fervor, declaring, “I like to go just as far as the farthest. I like my religion like my oysters and beefsteak, piping hot.” Carry Nation appeared at the crossroads between the old world order and the new. She represented old-fashioned moral values of home, hearth, and religion as well as the emergence of the new woman who rejected traditional roles. She both threatened and reassured people at the same time. Even the WCTU both embraced her and kept its distance, applauding her successes yet deploring her methods.

By 1910, Carry had worn out her welcome. After one last speaking tour, she moved to Eureka Springs, Arkansas, buying several homes including one she called Hatchet Hall, a unique woman-centered community for the wives and children of alcoholics, like her daughter Charlien, whose husband turned out to be an emotionally and physically abusive alcoholic. In 1911, she collapsed giving a speech in Eureka Springs Park and was taken to a hospital in Leavenworth, Kansas. She died of a nervous seizure five months later on June 9 and was buried in Belton, Missouri, near her mother. The WCTU later erected a stone inscribed “Faithful to the Cause of Prohibition, She Hath Done What She Could.”

Other books

Domning, Denise by Winter's Heat

Stepping into the Sky: Jump When Ready, Book 3 by David Pandolfe

Flying Hero Class by Keneally, Thomas;

The Cure by Teyla Branton

Unlocking the Sky by Seth Shulman

Alistair (Tales From P.A.W.S. Book 1) by Kupfer, Debbie Manber

My Soul To Take by Madeline Sheehan

Wrath by Kristie Cook

Vesik 3 Winter's Demon by Eric Asher

State of Emergency by Marc Cameron