Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women (25 page)

Read Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mahon

Tags: #General, #History, #Women, #Social Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women's Studies

Sarah hoped that another lecture tour of the East would not only help the Paiutes but restore her good name, which had been tarnished after the debacle with Schurz. In Boston, Sarah met Elizabeth Palmer Peabody and her sister Mary Peabody Mann, who became her most ardent supporters. Meeting them was the break Sarah needed. Elizabeth Peabody, considered the first woman publisher in the country, owned a bookstore frequented by the literati of Boston. The two women encouraged Sarah to write a book about the history of the Paiutes. The result was

Life Among the Paiutes: Their Wrongs and Claims

, the first book published by an Indian woman. A subscription was taken up to publish the book for six hundred dollars. An appendix with affidavits attesting to Sarah’s character was added to the book to counter attacks by Rinehart.

Life Among the Paiutes: Their Wrongs and Claims

, the first book published by an Indian woman. A subscription was taken up to publish the book for six hundred dollars. An appendix with affidavits attesting to Sarah’s character was added to the book to counter attacks by Rinehart.

With Elizabeth Peabody’s help, Sarah gave three hundred lectures from New York to Baltimore and Washington. Peabody was impressed by her protégée. Sarah didn’t use notes when she spoke, but somehow she never repeated or contradicted herself, trusting that the right words would come. The only fly in the ointment was her husband; apparently their joint bank account was a temptation that couldn’t be resisted. He not only gambled away her money but also passed bad checks. When Sarah found out, he skipped town, leaving her holding the bag. Sarah repaid the money from sales of her autobiography and her lecture fees, the money that she had earmarked to help her people. It was yet another stain on her reputation.

In 1884, Sarah spoke before the Senate Subcommittee on Indian Affairs. She proposed that Camp McDermit be established as a reservation for the Paiutes, and that the heads of family be allotted land of their own. More important, she requested that the goods and money be administered not by the Bureau of Indian Affairs but by the army. Although the House of Representatives passed the bill in 1884, the Senate refused to pass it as it currently stood. When the bill later passed, it affirmed Bureau of Indian Affairs control and condemned the Paiutes to Pyramid Lake, in Nevada.

When railroad magnate Leland Stanford gave her brother an undeveloped ranch in Lovelock, Nevada, Sarah opened a school for Indians called the Peabody Institute. She had long believed that education would make the difference, eradicating the distance between the two races. In an article in the

Daily Silver State

, she wrote, “It seems strange that the Government has not found out that education is the key to the Indian problem. Much money and precious lives would have been saved if the American people had fought my people with books instead of Power and lead.” Ill with rheumatism, she managed to run the school for three years until the money ran out. Although Mary Mann had left a small bequest to the school, it was not enough. The U.S. government denied Sarah additional funds, preferring to support schools like Carlisle in Pennsylvania that forced Indians to conform completely to white ways. In 1886, her estranged husband, Lewis Hopkins, died of tuberculosis. With the closing of the school, Sarah went to live with her sister Elma in Monida, Montana, where she died in 1891, possibly of tuberculosis, at the age of forty-six.

Daily Silver State

, she wrote, “It seems strange that the Government has not found out that education is the key to the Indian problem. Much money and precious lives would have been saved if the American people had fought my people with books instead of Power and lead.” Ill with rheumatism, she managed to run the school for three years until the money ran out. Although Mary Mann had left a small bequest to the school, it was not enough. The U.S. government denied Sarah additional funds, preferring to support schools like Carlisle in Pennsylvania that forced Indians to conform completely to white ways. In 1886, her estranged husband, Lewis Hopkins, died of tuberculosis. With the closing of the school, Sarah went to live with her sister Elma in Monida, Montana, where she died in 1891, possibly of tuberculosis, at the age of forty-six.

For most of her life Sarah was caught between two worlds, yet she worked tirelessly to preserve the traditions of her Indian culture. She fought against gigantic odds for the welfare of her people. While some saw her as a heroine, others considered her to be a sellout for advocating peace and for encouraging the Native tribes to try to understand whites. For her pains, she was distrusted at times by her own people and reviled and hated by those white men who were alarmed at the idea of an Indian woman challenging the establishment.

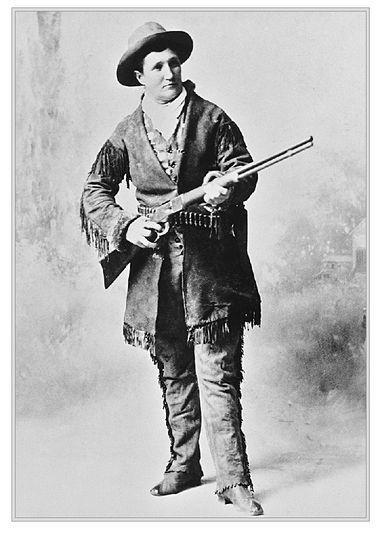

I’m Calamity Jane. Get to hell out of here and let me alone.

—CALAMITY JANE

By the time Calamity Jane came riding into Deadwood, South Dakota, at the side of Wild Bill Hickok in 1876, she was already well on her way to becoming notorious in the West. Barely out of her teens, she had acquired a reputation as a wild woman who drank and shagged with abandon. By the time of her death at the age of forty-seven she’d added gun-toting hellion who rode with Custer, Indian Scout, Pony Express mail carrier, and lover of Wild Bill Hickok to her list of accomplishments. The only trouble is that none of the above is true. Even over a hundred years after her death, it is still hard to separate fact from fiction. How did a foulmouthed, illiterate, drunken camp follower and dance hall girl become an icon of the Old West?

Born Martha Canary in 1856 in Princeton, Missouri, she was the oldest of Robert and Charlotte Canary’s children.

17

While her father was remembered as an inept farmer, her mother, Charlotte, was as notorious in Princeton as her daughter was in the boomtowns of the Old West. Her unconventional behavior marked her as different from the other frontier wives. Red-haired Charlotte wore eye-catching clothes in bright colors, swore in public, smoked cigars, and drank. Rumor had it that she met Robert in a bawdy house. Like mother, like daughter, as a child, Martha’s misbehavior and swearing got her into trouble. Although she went to school, none of it seemed to have stuck, since she was barely literate.

17

While her father was remembered as an inept farmer, her mother, Charlotte, was as notorious in Princeton as her daughter was in the boomtowns of the Old West. Her unconventional behavior marked her as different from the other frontier wives. Red-haired Charlotte wore eye-catching clothes in bright colors, swore in public, smoked cigars, and drank. Rumor had it that she met Robert in a bawdy house. Like mother, like daughter, as a child, Martha’s misbehavior and swearing got her into trouble. Although she went to school, none of it seemed to have stuck, since she was barely literate.

In 1862, the family left Princeton under a cloud, moving to Virginia City, Montana, where her father hoped to try his luck mining, but times were tough. An expert rider, Martha later claimed to have spent much of the trip “at all times with the men when there was excitement and adventures to be had.” But by the time Martha was twelve, both her parents were dead. Martha’s siblings were taken in by Mormon families in Salt Lake City, but Martha’s unruly behavior forced her out on her own. Orphaned, adrift, without the civilizing influence of a female role model, Martha added two years to her age and headed to Fort Bridger in Wyoming. She got a job tending children for a time but she soon began drinking and hanging out with the soldiers, which got her canned. Before long she was working as a dance hall girl and prostitute.

No one knows for sure how she acquired her nickname Calamity Jane.

18

In her colorful but inaccurate memoirs she claims that during the Nez Perce outbreak in 1873, she rescued Captain James Egan when he was wounded by ambushing Indians. When he recovered, Egan gave her the name “Calamity Jane, the heroine of the plains.”

18

In her colorful but inaccurate memoirs she claims that during the Nez Perce outbreak in 1873, she rescued Captain James Egan when he was wounded by ambushing Indians. When he recovered, Egan gave her the name “Calamity Jane, the heroine of the plains.”

Although she claimed in her memoirs to have been an Indian scout for Custer in Arizona, Calamity was little more than a camp follower. Crazy for adventure, dressed in an army uniform, she would join the troops as they went scouting. She generally seems to have joined them when they were far enough from civilization that it would have been cruel to send her back. The men liked her, treating her like a mascot. Calamity enjoyed the camaraderie of the men, who accepted her at face value. She cooked for them, nursed them when they were ill, and darned their clothes.

Calamity often ended up in the paper for her exploits, and not the heroic kind, such as the time she was arrested for stealing the clothes of two local women. She pleaded not guilty and was jailed in Cheyenne. When she was acquitted, Calamity paraded down the street wearing a dress lent to her by the wife of one of the sheriff’s staff. Continuing her celebration, she got drunk and then rented a wagon to drive the thirty miles to Fort Russell, only she was so out of it that she misjudged the distance and ended up passing it and arriving at Fort Laramie instead, which was ninety miles away.

Calamity owes her reputation as an icon to two men, Horatio N. Maguire and Edward L.Wheeler. Calamity’s local notoriety had captured the attention of Maguire, who was writing a promotional pamphlet on the Black Hills. A largely fictional portrait, he first introduced the idea that Calamity had been a scout in an Indian campaign. His fanciful description of her was picked up by several newspapers in the East where it came to the attention of Edward L. Wheeler.

19

Wheeler used Calamity as a character in a series of dime novels set in the Black Hills called

Deadwood Dick

. Deadwood Dick was sort of a Robin Hood of the Dakotas, with Calamity as his Maid Marian. Wheeler’s Calamity is beautiful, with flashing eyes, an able frontierswoman and strong horsewoman, comfortable wearing both buckskin and a dress. In the series, Calamity saves Dick’s life repeatedly while having improbable adventures.

19

Wheeler used Calamity as a character in a series of dime novels set in the Black Hills called

Deadwood Dick

. Deadwood Dick was sort of a Robin Hood of the Dakotas, with Calamity as his Maid Marian. Wheeler’s Calamity is beautiful, with flashing eyes, an able frontierswoman and strong horsewoman, comfortable wearing both buckskin and a dress. In the series, Calamity saves Dick’s life repeatedly while having improbable adventures.

The books sold thousands of copies, transforming plain Martha Canary to national heroine Calamity Jane. Because she was utilized as a character alongside such other larger-than-life heroes like Buffalo Bill Cody, Wild Bill Hickok, and Kit Carson, it was assumed that she had to be equally accomplished. A few months after Calamity’s appearance in Edward Wheeler’s dime novels, she was the central character in T. M. Newson’s play

Drama

of Life

in the Black Hills

. He, too, used the description of Calamity from Maguire’s pamphlet. In less than a year, she was a nationally known heroine. Calamity was in the right place at the right time. People back East were entranced with the romance of the West. During a five-year period from 1876 to 1881, from the massacre at Little Big Horn to the OK Corral shoot-out, the entire country couldn’t get enough of tales of the frontier.

Drama

of Life

in the Black Hills

. He, too, used the description of Calamity from Maguire’s pamphlet. In less than a year, she was a nationally known heroine. Calamity was in the right place at the right time. People back East were entranced with the romance of the West. During a five-year period from 1876 to 1881, from the massacre at Little Big Horn to the OK Corral shoot-out, the entire country couldn’t get enough of tales of the frontier.

Calamity’s life is a study in the fine art of mythmaking. Minor episodes in her life were blown up into epic adventures, and generic tales were tailored to fit her life until there was no semblance to reality. Take for example her relationship with Wild Bill. Calamity had only met him six weeks before they arrived together in Deadwood. She’d joined his expedition of gold seekers to the Black Hills, making herself useful as a cook and bushwhacker. Most eyewitnesses state that they were no more than casual friends, that Bill had no real use for Calamity although he loaned her twenty dollars to buy a dress. It wasn’t until later on that stories sprang up tying the two icons of Deadwood together, going so far as to claim that they were married.

Locals in Deadwood and other towns enjoyed repeating the tall tales of her exploits to gullible tourists. When it was reported that a woman was seen with a gang of outlaws, everyone claimed that it was Calamity. Stories were written that she had killed forty Indians and seventeen white men, that she had been with Custer at Little Big Horn. Others claimed that Calamity Jane tried to warn Custer of the danger he faced but she was held back by bad weather and pneumonia. While readers back East may have been entranced with the mythical Calamity Jane, journalists in the West were less sanguine. They seemed to delight in reporting her various drunken escapades and brushes with the law.

Calamity Jane became an icon not because of who she really was but because of what she represented. Both the mythical Calamity Jane and the real woman challenged society’s standards of behavior for women. By temperament, the real Calamity was easygoing, loyal to her friends, and full of sympathy for those who were sick or in trouble. In 1876, a smallpox epidemic swept through Deadwood. Hundreds of people fell ill, and most of the town was afraid to help because the disease was highly contagious. Dr. Babcock, the only doctor in town, recalled that Calamity risked her life to care for the dying miners.

Calamity just didn’t conform to the image of Victorian womanhood. She did what she wanted when she wanted. She smoked in public, wore men’s clothes, cussed, and drank in saloons where no respectable woman would dare be seen. “Lots of us knew the better side of Calamity,” remembered a man named Charles Haas. “She would go to these bawdy houses and dance halls, and it was ‘whoopee’ and soon she was drunk and then, well things sort of went haywire with old Calamity!” Local journalists recorded her comings and goings with barely disguised glee. But the realities of Calamity’s actual life, the drunkenness, the poverty, set her apart from her fictional counterpart.

Other books

The Giants and the Joneses by Julia Donaldson

The Constantine Affliction by T. Aaron Payton

Long Way Down by Paul Carr

Exodus: Book Two: Last Days Trilogy by Jacqueline Druga

Grail Quest by D. Sallen

The Sinner by C.J. Archer

The Dawn: The Bombs Fall (A Dystopian Science Fiction Series) by Muckley, Michelle

Action Figures - Issue One: Secret Origins by Michael Bailey

Dark Run by Mike Brooks

Sins Brothers [1] Forgotten Sins by Rebecca Zanetti