Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women (27 page)

Read Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mahon

Tags: #General, #History, #Women, #Social Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women's Studies

Horace moved Baby Doe into a lavish suite at the Clarendon Hotel. Local gossips called her “the hussy in a veil,” for her penchant for wearing one whenever she and Horace ventured out into public. Baby Doe knew their affair was wrong but she didn’t care. At last she’d found a real man, although grizzled around the edges. She knew it was just a matter of time before she was Mrs. Horace Tabor. Baby Doe was his confidante, listening to his troubles as he rested his head on her bosom. She encouraged his grandiose ambitions to turn Denver into “the Paris of the West.” Horace told her, “You’re so gay and laughing and yet you’re so brave. Augusta is damned brave too but she’s powerful disagreeable about it.” But after two years, Baby Doe wasn’t feeling so agreeable. She wanted to be made an honest woman. Finally she put her dainty foot down, informing Horace that as a good Irish Catholic girl she was risking her immortal soul by sleeping with a married man.

Augusta wasn’t prepared to let go of her husband without a fight. When he asked for a divorce, she refused. Instead she sued him for fifty thousand dollars for lack of support. Horace was sneaky, though. With Baby Doe’s encouragement, he decided to file for divorce in Durango, where he owned a mine. He managed to obtain the divorce from an unscrupulous judge who owed him a favor. The happy couple celebrated by getting secretly hitched in St. Louis. Baby Doe wasn’t happy about keeping it a secret but at least she had a marriage certificate. Finally, Augusta finally agreed to an official divorce but as she told the judge, “Not willingly, oh God, not willingly.” She made out okay, receiving $250,000, the mansion in Denver, an apartment block, and mining stock.

Horace’s actions cost him a chance to replace the retiring senator who had been appointed to President Chester A. Arthur’s cabinet.

22

Instead, as a consolation prize, he was allowed to serve out the final thirty days until a new senator was appointed. Horace accepted. He and Baby Doe headed to Washington, where he gave her a wedding that was talked about for decades. Sparing no expense to make his darling happy, the wedding took place at the Willard Hotel in March 1883. Baby Doe wore a seven-thousand-dollar white satin brocaded gown trimmed with marabou, a seventy-five-thousand-dollar diamond necklace around her neck. The decorations included a massive wedding bell made of white roses, topped with a floral cupid’s bow made of violets, and a canopy of flowers covered the ceiling. Although the wedding guests included the president, senators, congressmen, and cabinet members, their wives shunned the ceremony out of sympathy for Tabor’s ex-wife.

22

Instead, as a consolation prize, he was allowed to serve out the final thirty days until a new senator was appointed. Horace accepted. He and Baby Doe headed to Washington, where he gave her a wedding that was talked about for decades. Sparing no expense to make his darling happy, the wedding took place at the Willard Hotel in March 1883. Baby Doe wore a seven-thousand-dollar white satin brocaded gown trimmed with marabou, a seventy-five-thousand-dollar diamond necklace around her neck. The decorations included a massive wedding bell made of white roses, topped with a floral cupid’s bow made of violets, and a canopy of flowers covered the ceiling. Although the wedding guests included the president, senators, congressmen, and cabinet members, their wives shunned the ceremony out of sympathy for Tabor’s ex-wife.

Before the ink was dry on the marriage certificate, the Catholic priest who married them was furious to find out that he’d been duped into marrying a divorced couple. And the revelation of their earlier secret wedding hit the headlines. Baby Doe would never win the acceptance she craved from Denver society matrons, who refused to accept the former mistress of a married man as one of them. She wasn’t even repentant; she just turned her dainty nose in the air. To save face, she once told a newspaper reporter that although she had been “flooded with invitations from the very best people to attend all sorts of affairs, I have decided not to accept them so as not to create jealousy among the society leaders of Denver.”

One respectable and esteemed lady did pay a social call on Baby Doe: her husband’s ex-wife, Augusta. Although she claimed that she hoped for Horace’s sake that if she called, Denver society would follow, her later comments to the newspapers showed that her visit was anything but altruistic. “She is blonde and paints her face,” she told a Denver reporter months later. No doubt she just wanted to get an up close look at the woman who had taken her place.

Horace built Baby Doe a pretentious fifty-four-thousand-dollar Italianate mansion that occupied a whole block as a consolation prize. Set on three acres, it had the finest furnishings and art, including five paintings of Baby Doe, a staff of five, and a hundred peacocks, but few people ever set foot inside their showplace. While Denverites acknowledged Baby Doe when she appeared in public—in a series of carriages that matched her outfits—they still shunned her socially. Instead, Baby Doe spent her days cutting inspirational articles out of newspapers and magazines. Despite this, Baby Doe kept her sense of humor. When neighbors criticized the naked statues in the Tabors’ yard, she ordered her dressmaker to drape them in chiffon and satin costumes. And she defiantly breast-fed her children while driving through the streets of Denver.

Their two daughters, Lillie and Silver, kept her busy. She spoiled them, lavishing them with expensive toys and clothes. For her christening, Lillie wore a fifteen-thousand-dollar lace and velvet gown and diamond-studded diaper pins. A sketch of the baby by Thomas Nast graced the cover of

Harper’s Bazaar

. She was also featured in articles with titles like “The Little Silver Dollar Princess” in magazines across the country and in Europe. Baby Doe was so devoted to her children that she refused to leave them to travel with Horace.

Harper’s Bazaar

. She was also featured in articles with titles like “The Little Silver Dollar Princess” in magazines across the country and in Europe. Baby Doe was so devoted to her children that she refused to leave them to travel with Horace.

Horace had opened the Tabor Grand Opera House in Denver in 1881, which cost eight hundred thousand dollars and rivaled the opera houses of Europe. It was the opera house performers who treated Baby with the respect and deference she craved. In gratitude, she threw them lavish dinners at the mansion. Excluded from the social clubs and associations in Denver, Baby Doe gave generously to Catholic charities and colleges. On Christmas Eve she distributed toys, food, and clothes in the Denver slums. She even set aside two offices, rent free, in the block that Tabor owned for the use of Colorado’s women’s suffrage leaders. Although excluded from Denver society, Horace and Baby Doe were still welcomed in the mining towns and in New York, where money had begun to matter more than pedigree.

But the high life didn’t last long. After about ten years Horace began hemorrhaging money when the government stopped using silver as the monetary standard. He’d also plowed a ton of cash into speculative ventures that hadn’t panned out. Horace had continued to rely on luck instead of applying himself to following the market. Baby fended off creditors as best she could while Horace was out of town in Mexico working on his mines there. But by 1896, the opera house and the mansion had been seized by creditors.

Many thought that Baby Doe would dump Horace for greener pastures now that he was broke. Even his ex-wife, Augusta, had prophesied that she would “hang onto him as long as he’s got a nickel.” But Baby Doe was no fair-weather wife, although plenty of men were lining up, eager to take Horace’s place. No, she stubbornly believed that Horace would make a comeback. Even when Horace, like her first husband, Harvey, had to take a job as a day laborer in a mine, Baby Doe followed him into cheap lodgings, doing all the domestic chores herself.

But the best Horace could do was a job as postmaster of Denver. It paid $3,500 a year, and he was able to rent them a comfortable suite at a hotel. It looked like things might be turning around but a little over a year later, Horace died of appendicitis, leaving Baby Doe and their two daughters destitute. Legend has it that his final words were, “Hold on to the Matchless Mine . . . it will make millions when silver comes back.”

Although still beautiful, Baby Doe was now forty-five years old. Instead of moving back to Wisconsin to her family, she moved her daughters into a tenement, begging money from Horace’s old business acquaintances to reopen the Matchless mine. Finally Baby Doe moved back to Leadville, which had become a ghost town, to work the Matchless mine herself. In 1902, her daughter Lillie moved to Chicago to live with relatives. Although she and her mother continued to write, they rarely saw each other over the years. As she became increasingly religious, Baby Doe considered it scandalous when Lillie married her first cousin, particularly when she discovered it was a shotgun wedding.

Silver, on the other hand, had a wild streak like her mother but not her strength. She worked for a time as a journalist in Denver and wrote an unsuccessful novel called

Star

of

Blood

. Telling her mother she was going to join a convent, she, too, moved to Chicago, where she worked as a stripper, ending up hooked on drugs and alcohol. She died in a flophouse in 1925 under suspicious circumstances. When reporters came to Baby Doe for a comment, she insisted that it wasn’t her daughter, that she was in a convent.

Star

of

Blood

. Telling her mother she was going to join a convent, she, too, moved to Chicago, where she worked as a stripper, ending up hooked on drugs and alcohol. She died in a flophouse in 1925 under suspicious circumstances. When reporters came to Baby Doe for a comment, she insisted that it wasn’t her daughter, that she was in a convent.

Increasingly religious, she seemed to be doing penance for her past sins. Baby Doe exchanged her low-cut dresses for miner’s boots, an old black dress, and a huge black crucifix. She wandered the hills carrying an old sack. When hungry, she lived on stale loaves of bread that she bought twelve at a time, and scraps of beef. When her shoes were worn, she wrapped her feet in gunnysacks tied with twine. When she was ill, she dosed herself with vinegar and turpentine. She refused to accept charity unless she believed it was sincerely meant. She would return baskets of food left at her front door.

After her death, seventeen trunks were discovered in a Denver warehouse and also in the basement of St. Vincent Hospital in Leadville. In them were scrapbooks, a china tea set, bolts of expensive cloth, and the gold watch fob that Horace had been given by the citizens of Denver when the opera house opened. The items were auctioned off; most reside in the Colorado History Museum. Baby Doe and Horace are now buried together in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Denver.

Ironically, Baby Doe’s death brought her the acceptance that she had yearned for all her life. No longer was she the home-wrecking gold digger, but the noble widow who endured poverty and heartache, devoted to her husband’s last wishes. The

Denver Post

wrote, “Society, which had been quick to judge her as a frivolous coquette when she divorced her first husband and married Tabor, had learned in thirty-six years to wonder at and admire the quality of courage that held her to the old mine and its stark poverty.”

Denver Post

wrote, “Society, which had been quick to judge her as a frivolous coquette when she divorced her first husband and married Tabor, had learned in thirty-six years to wonder at and admire the quality of courage that held her to the old mine and its stark poverty.”

I don’t care what the newspapers say about me just so long as they say something.

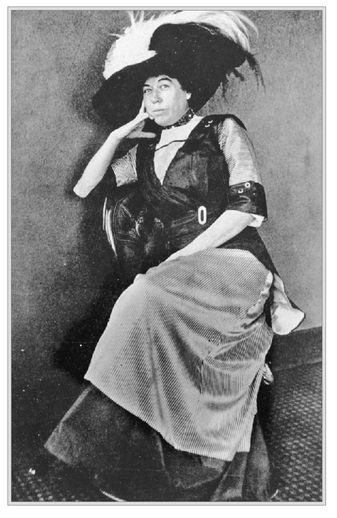

—MARGARET TOBIN BROWN

On her third night at sea Margaret Tobin Brown was settling down in her brass bed with a good book in her luxurious stateroom at the forward end of Deck B of the

Titanic

, when the massive ship experienced a jolt. Startled, Margaret decided to investigate. The engines of the luxury liner on its maiden voyage were eerily silent. “I saw a man whose face was blanched, his eyes protruding, wearing the look of a haunted creature,” she later wrote. “He was gasping for breath, and in an undertone he gasped, ‘Get your lifesaver!’” Rushing back to her room, she grabbed whatever warm clothing she could find: a black velvet two-piece suit, seven pairs of stockings, and a sable stole. Before she left her room, she grabbed five hundred dollars from the wall safe and strapped on her life jacket.

Titanic

, when the massive ship experienced a jolt. Startled, Margaret decided to investigate. The engines of the luxury liner on its maiden voyage were eerily silent. “I saw a man whose face was blanched, his eyes protruding, wearing the look of a haunted creature,” she later wrote. “He was gasping for breath, and in an undertone he gasped, ‘Get your lifesaver!’” Rushing back to her room, she grabbed whatever warm clothing she could find: a black velvet two-piece suit, seven pairs of stockings, and a sable stole. Before she left her room, she grabbed five hundred dollars from the wall safe and strapped on her life jacket.

Up on deck, Margaret calmly helped other women and children into the lifeboats, reassuring them that everything was going to be okay. She saw no reason to panic; she had dealt with the rough-and-tumble, male-dominated world of Leadville, Colorado, and not just survived but thrived. This was nothing in comparison. Suddenly she was picked up and unceremoniously dropped into a lifeboat along with two dozen other passengers. Quickly grabbing the oars at quartermaster Robert Hichens’s command, she helped to maneuver the lifeboat around just in time to see the ship break into two and sink into the ocean, disappearing under the ice-laden surface. It was an image that was seared on Margaret’s memory forever. She wanted to go back and look for survivors but Hichens ordered them to row. He thought they were doomed and said so repeatedly. Margaret admonished him, “Keep it to yourself if you feel that way. We have a smooth sea and a fighting chance!” Margaret encouraged the other passengers to help row. When she saw that one of the passengers in lifeboat sixteen, which was tethered to theirs, was only wearing pajamas, she wrapped her fur stole around his legs. She was later credited with keeping the passengers from freezing to death.

Other books

Degrees of Hope by Winchester, Catherine

The Wind From the East by Almudena Grandes

Odium II: The Dead Saga by Riley, Claire C.

Physical Touch by Hill, Sierra

In Too Deep by Stella Rhys

The Apocalypse Codex by Charles Stross

The House on Cold Hill by James, Peter

How to Marry a Cowboy (Cowboys & Brides) by Carolyn Brown

The Zucchini Warriors by Gordon Korman