Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women (30 page)

Read Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mahon

Tags: #General, #History, #Women, #Social Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women's Studies

She was born in San Francisco when Venus was in the ascendant, blessing her with beauty and charm, according to astrological interpretation. Her father, Joseph Duncan, was a poet, journalist, and deadbeat dad who left his family soon after Isadora was born. After the divorce her mother, Dora, gave piano lessons to make ends meet. They moved from lodgings to lodgings, leaving debts behind, a pattern Isadora would repeat her entire life. Despite the lack of material goods, Isadora’s mother instilled in her children a love of art, reading to them from Shakespeare, Byron, and Isadora’s personal hero, Walt Whitman. The children did whatever they pleased without worry of being disciplined.

Isadora always claimed that she absorbed her first impression of movement from the rhythms of ocean waves. By the time she was six, she was teaching the other children to wave their arms to music. By the time she was ten, she had dropped out of school, convinced that there was nothing that conventional education could teach her. While she had little formal training, she knew the popular dances of her day, and she studied the theories of François Delsarte, although she didn’t like to admit it. The French musician and teacher believed that natural movements were the most genuine and could be used to interpret music. Her dancing incorporated only those movements that were natural to the body, which led her to reject ballet, which she considered abnormal. Dance at the time wasn’t really considered an art. Isadora wanted to change that, to place dance alongside music, sculpture, and painting.

At eighteen, Isadora was convinced that San Francisco was too provincial to understand her art. The family moved to Chicago with only a small trunk, twenty-five dollars, and some jewelry. Isadora auditioned in her cute little white tunic for various producers but there were no takers. After months of no work, Isadora got an audition at the Masonic Temple Roof Garden. The manager, however, told her that she could perform her original dances if she also performed what they called a “skirt-dance” number. Isadora lasted three weeks before she quit, disgusted at having to “amuse the public with something which was against my ideals.”

Next stop was New York. If she could make it there, she could make it anywhere. After two years touring with Augustin Daly’s theater company, she met a young composer with whom she gave five solo concerts at Carnegie Hall. Things began to turn around when Isadora was taken up as a sort of pet by wealthy society matrons who invited her to dance in Newport and at their mansions on Fifth Avenue. High society applauded, but it didn’t pay the rent. The final straw for the family occurred when the hotel where they were living burned, along with all their possessions. It was time to make her mark in Europe, where she was convinced her art would be appreciated. With only three hundred dollars, the family had to cross the ocean on a cattle boat. Isadora’s mother cooked for the crew to help pay for their passage.

London and Paris proved to be more hospitable. She made her Paris debut, and audiences adored her. It was in Paris that Isadora developed the idea of dancing from the solar plexus, whereas classical ballet emphasized dancing from the spine. Soon she went off on a tour of Hungary and Germany; in Berlin, the audience mobbed the stage and refused to leave. Newspapers were filled with interviews with “Holy Isadora.” One night she improvised to Johann Strauss’s “Blue Danube” waltz, which was a huge hit. Wagner’s son invited her to dance at Bayreuth in

Tannhäuser

, but her new style clashed with the ballet dancers hired to dance the Bacchanal with her. In Greece, Isadora danced among the ruins.

Tannhäuser

, but her new style clashed with the ballet dancers hired to dance the Bacchanal with her. In Greece, Isadora danced among the ruins.

Isadora not only influenced the future and evolution of modern dance but also the first modern ballet company, the Ballets Russes. Both impresario Sergei Diaghilev and the choreographer Michel Fokine were taken by her on trips to St. Petersburg in 1905 and 1907. Diaghilev thought she gave an irreparable jolt to classical ballet in imperial Russia. Fokine wrote that “she reproduced in her dancing the whole range of human emotion.”

She founded her first school, in Grünwald, Germany, to teach not just dance but also what she called “the school of life.” “Let us teach little children to breathe, to vibrate, to feel and to become one with the general harmony and movement of nature. Let us first produce a beautiful human being, a dancing child.” While Isadora was inspirational, she wasn’t great at communicating her techniques. That was left to her sister Elizabeth, who taught at the school for years until it closed. It was the first of many schools that Isadora would found in her lifetime. The school gave rise to her most celebrated troupe of pupils, dubbed the Isadorables, who eventually took her surname and later performed both with Duncan and independently.

But artists cannot live by acclaim alone. Who would finally initiate her into the delights of Aphrodite? For such a free spirit, Isadora was still a virgin at twenty-five. In Hungary, she was finally introduced to the pleasures of the flesh when she met the actor Oscar Beregi, whom she immortalized as Romeo in her autobiography. They met at a party in her honor. Beregi was twenty-six, tall, dark, and handsome. Soon he was declaiming poetry from Ovid and Horace, backed by a chorus, in between her dances. Isadora was in love but Beregi expected her to give up her career to support his. Isadora was determined to stay free. Still, all her life she would be torn between love and her art.

The great love of her life was probably the stage designer Edward Gordon Craig. Gordon Craig was a creative genius as well as a misogynistic bastard. The father of eight, he’d already abandoned a wife and a mistress and was now living with his commonlaw wife. Introduced after one of Isadora’s shows, he soon invited her up to see his etchings and she stayed for four days. She fell madly in love with him. “A flame meets flame; we burned in one bright fire.” Isadora abandoned her art for a time, lost in passion. She bore him a child, Deirdre, in 1906. The relationship eventually crashed and burned over their fierce jealousies of each other.

The longest and most enduring relationship of her life was with Paris Singer, the sewing machine heir. Named after the city of his birth, Singer was tall, blond, bearded, and looked like a Nordic god. She called him Lohengrin in her biography, after Wagner’s hero, and later claimed that he was the only man she’d ever loved. He was rich, worldly, and a generous patron of the arts. He brought luxury and devotion into her life. Once again, her career took second place to her new love as she spent time sailing on his yacht or at his villa. “I had discovered that love might be a pastime as well as a tragedy. I gave myself to it with pagan innocence.” She gave birth to their son, Patrick, in 1911.

On April 19, 1913, Deirdre and Patrick drowned when the car they were riding in accidentally rolled into the Seine. Isadora’s life could now be divided into two parts: before and after the tragedy. She never spoke of her children again, and for years afterward the sight of a blond child moved her to tears. Following the accident she went to Corfu with her brother and sister to grieve and then sought solace with her friend Eleanora Duse at her villa in Viareggio, Italy. Isadora didn’t dance for two years. When she returned to the stage, Europe was at war, and Isadora infused her dancing with her grief, channeling the sorrows of the world. She added an impassioned rendition of “La Marseillaise” to her repertoire.

She broke with Singer, who was turned off by her habit of making public scenes. The final blowup came after he booked Madison Square Garden for a performance by her school. When Isadora heard the news, she sarcastically replied, “What do you think I am? A circus? I suppose you want me to advertise prize fights with my dancing?” Singer was livid; he got up and walked out. Isadora was sure that he would be back but it was over. He cut off her funds and refused to see or speak to her for a long time.

Professionally, Isadora’s pupils caused her both pride and anguish. The Isadorables were subject to ongoing hectoring from Duncan over their willingness to perform commercially. Where once she claimed not to be jealous of the dancers, she now considered them to be her rivals and envied their success. Only Irma Duncan (no relation) would be the most faithful of her acolytes, following her to Russia in 1921, where she taught in Moscow for seven years. Returning to the States, Irma continued to teach Duncan’s techniques until her death in 1977.

America had never embraced her with open arms the way Europe had. Her atheism, love affairs, illegitimate children, and lack of embarrassment were a little out-there for early-twentieth-century America. During the war, she moved herself and her students to safety in New York, where she hoped to open a school, but she was too outspoken about America intervening in World War I and about free love, and she flouted the puritanical codes of the country. Even her native city, San Francisco, gave her the cold shoulder. Isadora became convinced that Americans had little appreciation for art and beauty, or at least her version of them.

By the end of her life, Duncan’s performing career had dwindled and she became more notorious for her financial woes, and all-too-frequent public drunkenness, than for her dancing. There was an ill-fated attempt to start a school in Soviet Russia and a disastrous marriage to Sergei Esenin, a mentally unstable poet seventeen years her junior, which ended with his suicide. Her espousal of communism made her persona non grata in the United States. She had lived long enough to see her style and technique be considered old-fashioned and perhaps a little bit out of touch. Barefoot dancing was no longer new and innovative. She spent her final years moving between Paris and the Mediterranean, running up debts at hotels. By the time she sat down to write her autobiography, she hadn’t danced in three years. Her love of luxury eventually led to her death, in Nice. Settling into her seat as a passenger in the Bugatti she was thinking of buying, with a handsome French-Italian mechanic, her long, embroidered Chinese red scarf became entangled around one of the vehicle’s open-spoked wheels and rear axle. When the car sprang forward, the scarf tightened, snapping her neck. Her last words had been

“Adieu, mes amis, Je vais à la gloire.”

(“Good-bye, my friends, I go to glory.”)

“Adieu, mes amis, Je vais à la gloire.”

(“Good-bye, my friends, I go to glory.”)

After lying in state in Nice and Paris, her funeral was scheduled on what was the tenth anniversary of America’s entry into World War I. The American press, who had never understood her, wrote that her funeral cortege was barely noticed as the American Legion parade wended its way down the Champs-Élysées. There was no report of the ten thousand people who gathered at the cemetery or the one thousand who crowded the crematorium as her favorite music played. Her ashes were placed next to those of her beloved children at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

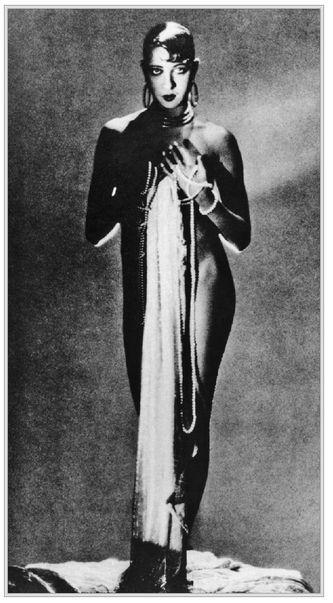

There is no film of Isadora dancing, which is perhaps as she would prefer. Isadora claimed that she preferred to be remembered as a legend. She died before the advent of sound recording, which would have allowed the cameras to capture her performance with the music that inspired it. One can only get a sense of the glory and passion of her art from still photos, the dancers that she inspired, and the reviews and memories of those who saw her dance. While her schools in Europe did not survive for long, her work can be felt in the many dancers and choreographers that she influenced.

What a wonderful Revenge for an Ugly Duckling!

—JOSEPHINE BAKER

On the night of October 2, 1925, audiences had no idea what to expect when the curtain rose at 9:30 p.m. at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, on a new show from America called La Revue Nègre. Then Josephine Baker burst onto the stage, letting rip with a fast and loose Charleston. At the end of the show, she reappeared naked except for beads and a belt of pink flamingo feathers between her legs, carried upside down in a split, by her partner, bringing a little bit of Africa to France. It was the event of the season. Critics in Paris thumbed through their thesauruses trying to outdo themselves with animal metaphors and exotic imagery to describe her performance.

Other books

White Jade (The PROJECT) by Lukeman, Alex

Hot Property (Kingston Bros.) by Larson, Tamara

Shattered Rose by Gray, T L

Instinct by Sherrilyn Kenyon

Criminal Intent (MIRA) by Laurie Breton

Seven Letters from Paris by Samantha Vérant

Dark Skye by Kresley Cole

Gambler's Folly (Bookstrand Publishing Romance) by Mellie E. Miller

Learning to Let Go by O'Neill, Cynthia P.

Killswitch by Victoria Buck