Scarface (18 page)

Authors: Andre Norton

It took a full long minute for them to understand that, for their attention to swing from Cheap to the boy under Cocklyn’s hand—while

he

looked dumbly not at the others but at Cheap who now stood dominating them all.

“Aye, your son! Look well upon my handiwork, Robert Scarlett! Potboy, scarface, renegade pirate, thief and murderer, condemned to hang with the dawn—there is your only son. And so at long last are we two quits at this world’s gaming table. Because all your days you will have a sweet memory to hold by you—you helped to hang your only son!”

“This is true?” The Governor’s voice was very controlled and yet it cut through the other’s fine ranting like a ship’s prow through the waves.

“True? Aye, have up Creagh or Peter; they’ll answer you straight enough. You know them both of old. But you know that I speak the truth, Robert Scarlett, you know that very well.”

Scarlett bowed his head. “You do—God help me—you do!”

Cheap’s smile was that of a victor. “You will excuse me

now,” he said to them all. “I have only a few hours left to me and I am fain to sleep since I would go fresh to my hanging. You give me leave to go?”

“Not yet, Captain Cheap,” Scarlett returned almost briskly. He made a sign and Cocklyn produced from a pocket a package wrapped in a bit of stained cloth. He pulled off the cloth and gave to the Governor a small gourd which still contained a sticky black paste.

“As you perceive by this we have already had speech with Ghost Peter. In fact it was upon that affair that we had come hither. I believe you know of this—a sovereign remedy for the coast fever, is it not?” He paused courteously for the answer which Cheap did not make. The wild elation was gone out of the Captain; he was wary now, on guard against a new danger.

“Only it is a remedy which no sane doctor will use—because it plays strange tricks with men’s minds. However, being no doctor, you were willing to take that risk, weren’t you, Jonathan? Why—? Because you did not want to lose your weapon against me? Was that it, Cheap? And would it have been even more amusing if the drug had worked as it sometimes does and you could have shown me a drooling idiot as my son—would it?”

Cheap’s mouth was a beast’s snarl of rage.

“How you must hate me, Jonathan Cheap. Almost as much as I hate you!”

“Only I’ve won,” spat the Captain. “Your pirate son will swing with me.”

“Will he? You underrate our justice, Cheap. You see, I thought his bearing at the trial was odd and there were

points in Francis Hynde’s story which gave me to think so strongly that I came here tonight with witnesses. Peter talked, he had no reason not to, because he looks upon his drug as an honest one and his cure something to boast of. He talked very well, did Peter. And now you yourself have supplied the missing evidence. No, Jonathan Cheap, I do not think that my son will hang tomorrow. But I know that you will!”

“Do not think that you shall keep him from the gallows because he bears your name!” shouted the Captain. “Even a governor cannot do that!”

Justice Acton spoke then. “On fresh evidence the prisoner has been remanded. I assure you it is very legal, Captain Cheap. Even Her Majesty will find no fault with the Courts of Barbados.”

“Keep the whelp then! And I wish you the full joy of him! Since I have had the fashioning of him from his birthing he will bring no pride to you. And the day will come, Robert Scarlett, when you shall wish that you had let well enough alone and left him to dance on air. You see, I know well my Scarface.”

Chapter Eighteen

OUT OF THE SEA, INTO THE SEA

“DO YOU?” mused Sir Robert. “I wonder. I mind me of many times in the past when you were wrong. You have ever been plagued by too great estimate of your own powers.” He yawned. “Now it’s a little late to settle these matters and, since we all have an important engagement on the morrow—” He arose with the air of one speeding parting guests.

“May the Devil blast you—Robert Scarlett,” breathed Cheap and his face was a gargoyle mask of red hate.

Scarlett laughed and that jeering answer seemed to bring Cheap to his senses again, so that he was his own man once more as he made a sketchy bow to the company.

“Laugh while you may, Your Excellency, but he who enjoys the jest most, laughs last. You may find that the dog still has some fangs in his jaws.”

With that he was gone, shouldering aside the guard at the door so that the fellow needs must haste to catch up with his prisoner.

“That is Cheap for you,” observed Sir Robert. “He must ever have the last word or he deems himself robbed by fate.”

“You do not think that there is aught in what he said?” ventured Cocklyn.

“He has said many things here tonight, and most of them surprising. Which statement do you question now, Humphrey? The one that Blade is my son? No, in that Cheap speaks the truth.”

“How do you know?” Scarface got it out at last, that protest against this last trick Cheap had played him.

They all turned to him. Acton was frowning, Cocklyn surprised, but a quirk of a smile lifted Sir Robert’s long upper lip. And of the three, Scarface liked that smile the least.

“Is it so hard a fate to face?” asked the Governor with all his old biting mockery. “Faith, my reputation as a man-hunter must be a grim one. But at the cost of setting all your worst fears alert I must say that, aye, you are my son. I will accept Cheap’s word in this matter because I know the man, and such a trick is well like his contriving. Then too, were it not for that scar, you might be thought

twin to Godfrey Chalmers of Jamaica who was my lady’s younger brother. ’Twas that likeness which I noted from my first meeting with you. You are, in spite of all your hopes, Justin Scarlett.”

“Your Excellency,” Acton protested, “the law must have better proof before accepting such a wild tale—the word of a condemned rogue—”

Sir Robert’s eyebrows rose. “Must it? Then we shall contrive to give it some. But let us adjourn this discussion, gentlemen. As I observed before, the hour grows late and I have a fatiguing task awaiting me tomorrow. You will excuse us? Come, Justin—”

Unwilling, but not daring to disobey that order, Scarface followed the Governor out of the room at a pace which he tried to make as slow as possible. But only too soon were they out in the street where a detachment of the guard waited them with the coach and so rode in state back up the hill.

Once inside the palace, Justin would have crept away to what had been his own quarters, but the hoped-for dismissal from Sir Robert’s presence did not come. Instead he was ushered into the Governor’s own chamber where a waiting slave hurriedly set candles ablaze and then was waved out of the room. The boy moved his feet and glanced longingly at the door but Scarlett had no pity on him.

“Here’s a pretty to-do.” Sir Robert threw himself into a wing chair. He might either have been addressing Justin or thinking aloud. “What am I going to do with you now?”

“If it please you, sir,” Justin broke in eagerly, “I’d as leave go—I make no claim on you—truly, Your Excellency—”

“So Cheap hit near the truth after all. D’you hate me as much as all that, lad?”

“Hate you?” Justin was honestly bewildered. “I have no reason to hate you, sir. This night you saved my life—”

“Having first thrust your neck well into the noose. Aye. But then by just naming a man ‘son’ you cannot fully win him. However, we’ve all time before us to know each other better. Faith, by the look of you now, the fever’s still in your bones. Take the far chamber there and get you to bed. On the morrow we’ll have the doctor in to you. But there’ll be no more devil’s potions down your throat—that I promise.”

Justin mumbled his thanks and went into the room Sir Robert had indicated. Pulling off his clothes he crawled between the fine sheets of the curtained bed and was asleep from sheer exhaustion almost before his head was centered on the pillow. Nor were any dreams able to break his rest. But in the other room the dawn light struck full across time-yellowed papers over which His Excellency had been busy the night through.

There was a pattern of sunlight on the wall, dappled by the shadows of leaves. Justin blinked once or twice at it and then sat upright in the wide bed. As if that sudden move had pulled a bell cord a slave arose quickly from the floor and grinned wide-toothed at him, then vanished through the door to reappear at the head of a small procession of his fellows bearing a wooden tub, cans of water, towels and other aids to a gentleman’s toilet.

So did Justin for the first time in his life fall into the hands of a trained body servant and find himself after a

somewhat breathless half hour well bathed, shaved and clad, ready to face the most critical society. He ate of the food they brought him, and it was only after they had taken away the empty dishes, that he began to wonder why he had seen or heard nothing of Sir Robert. When he ventured to ask one of the slaves, the fellow only shook his head and said something about “duties.”

“So there you are!” piped a very familiar voice from without the long window. Then, without waiting on an invitation which might not be given at all, Francis Hynde swung a leg over the sill and pulled himself in.

“Didn’t he let you go either?” he demanded, full of some personal slight. “My Uncle Humphrey locked me in—did Sir Robert lock you?”

“Lock me—why?”

“So you wouldn’t go to see the pirates hung? That’s where all the island is now—down watching the hanging. But Uncle Humphrey brought me here and locked me in so I couldn’t go. I climbed out the window but I can’t get over the wall, not unless someone gives me a hand up—” He regarded Justin hopefully. “You could climb it, I think,” he added coaxingly.

Justin shook his head. “No. Haven’t you had enough of running away, Francis? Next time your good luck may not hold.”

“But I’m not running away,” clamored the Baronet. “I but want to see the hanging. Don’t you?”

“There is nothing I would care for less,” returned the older boy truthfully.

“But you aren’t going to be hung, Justin—I heard my

uncle say so to

my mother this very morning. Why, you’re Sir Robert’s son!” His eyes were wide with wonder at that thought. “I’ll wager that you could tell the sentries at the gate to let us through and they would obey you. Please do so, Justin. This is the finest hanging they have ever had in Bridgetown and we shall miss it all!” Sir Francis looked dangerously near the tear line.

Justin, badgered almost beyond control, flared back. “Stop your whining! I have no wish to go to the hanging, and if your uncle does not want you to go, then you will not either! You’re long out of petticoats, Francis; stop playing the silly child. Cheap was passing kind to you—do you wish to see him choked out of life!”

Francis shrank away from him, his head shaking from side to side. “Please, Justin,” he began almost timidly, “do not be angered with me. But it is so dull here—let us go to feed the birds anyway. Please—?”

Because he had nothing better to do, Justin followed the younger boy out into the garden and watched him take a small bag of grain from the chest in the covered way which led to the stables. But he did not go inside the bird sanctuary with Francis. The talk of hanging made him think of the future—his future—and that was not the most pleasant thing to dwell upon. Nor was the past either! What if Sir Robert had not marked those discrepancies in Francis’ testimony, what if he had not investigated Ghost Peter’s part in the story, then—then at this very hour— He half consciously raised his hands to his throat, touching the fine linen of neckcloth rather than a hempen circlet which might have been there. At this very hour—!

He could stand it no longer. Turning, he ran back into

the palace, hunting the way he had heard of but had never ventured to explore, that semi-private stairway which led to the Governor’s own railed walk on the roof, fashioned so that Sir Robert could view his ships.

Up there the sun was hot, beating on his uncovered head and bringing out the perspiration on his coated shoulders. But, even without the aid of the brass-bound glass which lay close to his hand in its box, he could see the sweep of the harbor and the boats clustered there about the point on which stood a raw new gallows where men had labored the night through to build a machine to take their fellows out of the world. By the number of small craft pulled up about the point, half the island must be assembled there, and the other was surely to be numbered in the dark mass along the shore. He was too late to witness the procession of the condemned. They were already at the place of execution. He reached for the glass quickly.

That was Creagh they were turning off now. The hangman was not clumsy, and knew his work well, for that thick neck must have been broken cleanly, to give the boatswain the quick death he had denied others. Strange to see Nat Creagh, who had come to mean to him all the lurking cruelty of the world, go so tamely to his end.

But now— Justin’s fingers tightened about the glass as he watched a slim, erect figure walk beneath the swinging feet of the boatswain. Even with the glass it was too far to see Cheap’s expression, but from his bearing he might still be on his own quarter-deck with a wide-open sea before him. Jonathan Cheap was no broken man. He was addressing the crowd, and Justin did not doubt that he was doing it well. And now the Captain mounted the ladder

only—only—something had gone wrong. Cheap turned, his arms free from his sides as if his bonds had fallen away. He gave a great leap out away from the reach of the guards who moved toward him seconds too late. There was a bobbing and milling in the crowd and Justin screwed the eyepiece of the glass half into his skull trying to make out what was happening. Had Cheap won free this time also?

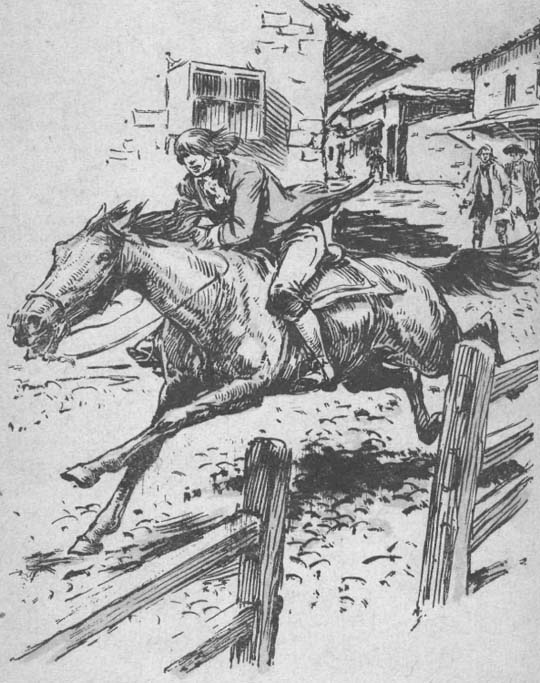

The boy dropped the Governor’s fine glass and pounded down the stairs. Half out the door he bethought himself that a man on foot could not win through that throng below—but a mounted man might have a chance—so he headed for the stables where, as luck would have it, a downcast groom was even then saddling a wire-legged roan.

Almost dancing with impatience Justin let him finish the business and then shoved the servant out of the way to swing rather clumsily up—since of horses he had not the knowledge that he had of ships. Before the surprised groom could raise a shout of protest, Justin had given the roan its head and was down the avenue. A sentry would have barred the gate, only at the last minute the man jumped aside, having no wish to play martyr to this mad rider who was drubbing his mount with spurless heels in order to urge an already wild horse to greater speed.

They took the cobbled street at a pace which a more prudent rider would have curbed, but the horse regained its sense and slowed its gallop as they came into the main town. It mouthed the bit angrily and gave no heed to Justin’s awkward guidance, being a settled animal of comfortable years.

So when they cut into the fringe of the crowd by the

. . .

at a pace which a more prudent rider would have curbed.

wharves, those disappointed of better places for the show, it was a walk, a slow enough pace for Justin to catch the first of the rumors.

“ ’Tis th’ truth as I do swear, neighbor,” gabbed a small man in the neat coat of a clerk. “Th’ pirates won free at th’ very gallows’ foot an’ are now come to murder us all. Evil day when this came upon us—”

“You ’ave th’ wrong o’ it!” protested another, held tight in the press some feet beyond him. “Th’ Governor it were, Sir Robert hisself. Th’ chief rogue did pistol ’im— before all th’ town! I did ‘ear that fisher cove say it an’ ’e were within a ’undred yards o’ th’ gallows when it ’appened. With ’is own eyes ’e seed it!”

“Be Sir Robert dead?” shrilled a woman and her cry was taken up by those about her.