Scribbling the Cat: Travels With an African Soldier (17 page)

Read Scribbling the Cat: Travels With an African Soldier Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Military, #General

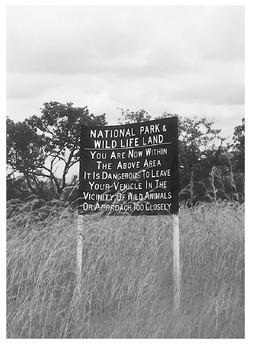

Road sign, Zimbabwe

K LOOKED AT ME SIDEWAYS. We were climbing out of the valley into which Lake Kariwa spills, gushing out of the gorges of the Pepani River and slamming to a standstill at the wall near a rock that the Tonga people call Kariwa—the trap. This escarpment was a road of memories for K. He moved here with his young wife a few years after the war and this was where his son was born, and died. He said, “I love this valley,” and his jaw bulged in a way that I now recognized as a prelude to something that made my heart grab at the edges of my ribs.

“The ex was such a . . . She’s tiny,” he said, “but very strong. She works out in the garden all day, like she’s . . . trying to run from something. Well, she is. She is trying to run from something.” He paused and said, matter-of-factly, “She’s possessed.”

I realized then that we had slipped—as periodically happened—off the edge of normal conversation into K’s mind, where he was at his most paranoid and angry.

“Possessed?”

“Ja. By demons. Ja.” His lips slapped shut with finality. It was a long time before he said, “You know, she never got over Luke. She can’t leave that poor boy to rest in peace. Luke’s room, all his clothes, everything, even his ashes. They’re all in his cupboard. Everything washed and folded and in his cupboard like he’s going to come home after lunch for his afternoon rest. She’s even left his toys where they were when he died. All his stuffed animals are on his bed. . . . It’s all there. And she spends hours sitting on his bed, like she is waiting for him. To this day, she’s there. Every day. She’ll never leave Zimbabwe. She’ll never leave that boy alone. If those ‘landless peasants’ come for the house, they’ll have to kill her or let her live there with them because they won’t get rid of her.”

I said, “I don’t think that’s being possessed. That’s grief.”

K shook his head. “No. You don’t understand. I actually saw the demons entering her. I woke up one night and I watched the demons fighting for her soul. If I hadn’t woken up . . . I pulled the sheets up around her and I told them to fuck off and they went back out the window. The demons—well, there was one in particular, like a cat’s head floating there, black and with bright green eyes, that was trying to get into her. But I chased it out. I used the power of the Almighty to chase it out. But the ex has never believed, really. She used to say that she did, but she doesn’t. And since then, oh ja . . . she’s evil. She opened herself up as a house of Evil and they came. She’s possessed.”

I don’t underestimate the power of ghosts and spirits and, at that moment, I could feel K’s own demons. They were burning and noisy and hard-edged and they were churning about in the front of the car. The windows were open and the air was rushing around us, hot and black from the tarmac, but it couldn’t sweep the demons out of the car.

“When we were going through all our shit”—by which I assumed K meant the affair that he said his ex-wife had had—“I knew she was possessed. What else would make a woman do what she did?”

I puffed hard on my cigarette and said nothing.

“About ten years ago, when we were still trying to work out our marriage, I prayed to the Almighty, what should I do? I read that the answer to my problem could only be resolved by prayer and fasting. For twenty-five days I prayed and fasted and then I waited for God to tell me what to do next. Nothing. I waited three days. On the third day, He told me to visit the ex. I was with Dingus at the time.

“I told him, ‘Dingus, the Almighty has sent me to her.’

“I was—I was so sure that God was going to send the demons out of her. I could feel His power all around me. Dingus dipped his finger in cooking oil and he drew a cross on the windscreen, right there”—K pressed his finger against the windshield and drew a cross on the glass—“right there.” K glanced over at me to make sure he had my attention, which he did. Every nerve was prickled. I felt as if I was sitting in a small chamber of ever advancing needles. “Dingus came with me. We drove to the ex’s house and I got out of the pickup. The gate was locked. I called for her, I hooted. I shouted some more. I knew she was in there. I could just

feel

she was in the house. When she came out, she had a gun with her.

“I asked her, ‘What’s the gun for?’

“She said, ‘Leave me alone.’

“I said, ‘I need to talk to you.’

“We went back and forth for quite a while like this, hey. Eventually, she let me in. We went into the house. I told her to put the gun down. I mean, I am the one that taught her how to shoot the blerry thing and she can shoot straight, that woman. I fixed the trigger on the pistol to make it less stiff for her. That’s when I did this.” K lifted his left leg and showed me the holes in his calf and ankle, which I had correctly assumed were bullet wounds. “See? Bullet went in here”—K pressed his calf—“and out here. I always used to wonder what it would feel like to get shot, and then I shot myself by accident and found out. It hurts like sterek

,

man. Shit, it hurts.

“Anyway, I told the ex, ‘The Almighty is my shield. Put the gun down.’

“She told me, ‘Your God is your God, and I respect that. But I don’t communicate with Him.’

“And I told her that she needed to get onto her knees and ask His forgiveness.

“She said, ‘No.’ Then she said, ‘Leave me alone.’

“I said, ‘Can I pray for you?’

“She said, ‘I want you to leave now.’

“I put my finger on her cheek and she screamed at me, ‘Don’t touch me.’

“I thought, I honestly thought, that I’d feel something. That God would give me the power to heal her. What I felt was”—K flicked the top of my arm—“like that, a small electric shock. That was all. Nothing else.”

By now we were beyond the road that snakes out of the Pepani Valley and that describes the long eastern border between Zambia and Zimbabwe which surfaces at Mkuti. Here, the Pepani Escarpment gathers to a long, undulating ridge as far as the eye can see; a quivering headdress of spring-red msasa leaves and lichen-covered branches. A gray cloud swung its belly over the brush at the summit and fat drops of rain burst on the windscreen and splattered into the car and dotted up and down my arms. I hung out of the car and let the rain fall on my face.

K said, “When I drove home, the cross that Dingus had made on the windscreen with cooking oil, it nearly drove me benzi, I tell you. I kept staring at it and I wanted to wipe it off the windscreen. It hadn’t bothered me when I was driving out to the house, but coming back, it was making me crazy. What does that tell you?”

I brushed the rain off my forearm and pressed myself against the door. “Maybe the light hit it differently,” I said. Since K kept his car, like everything else in his life, meticulously washed and clean, I was not surprised to hear that he found a smudge of oil on his windscreen annoying.

“No,” said K, “it tells me that I had Satan within me. And when I got home to Dingus’s house, he made some tea and I took the cup from him and I found my hand was shaking so much I couldn’t get the cup to my lips.” K took his hand off the steering wheel to demonstrate how much his hands had been shaking. His hand fluttered in my face, like a bird trapped indoors. “Just like that. And the next thing I knew I was on the ground and this . . . scream . . . It wasn’t me. It wasn’t my voice. It was something else. This powerful scream came out of my throat. A roar, I guess. It was like a lion and it felt like my neck was going to burst.” Looking at K’s neck now, I had the same concern. “And this great yell. And then I blacked out.”

He gave me a long, significant look. He said, “That was the power of the Almighty. That was the Almighty fighting Evil.”

Anyone who has, involuntarily or voluntarily, starved in the course of her life knows the light-headed, almost hallucinatory effect of an extensive fast. I said, very quietly, “You don’t think you just needed a square meal in your tummy?”

“You think I’m benzi, don’t you?”

“No,” I said. And then, “Well, yes. A bit.”

“Do you believe in love?”

“What?”

“Love,” insisted K urgently. “Do you believe in it?”

“I don’t understand.”

“Can you see love?” K persisted but before I could reply K shook his head. “No,” he said. “No, you can’t.” He let this sink in before saying, “The ex made me go to a shrink after that. She also thought I was benzi.”

“Yes.”

“The shrink told me God wasn’t real. She told me that I couldn’t see God or demons. That I was hallucinating or imagining stuff.” K was sweating. Under the spice of his aftershave, he exuded wood smoke, the singe of charcoal-ironed clothes, and an aroma like a freshly turned field. “So I asked her, ‘Do you believe in love?’

“She said, ‘Yes.’

“So I said, ‘But you can’t see it, can you?’

“She said, ‘No.’ ”

K started to laugh humorlessly. “It’s the same with God. You can believe in Him without seeing Him. He’s there! He’s there!” He slammed his fist into the dashboard twice to emphasize his point.

I said, “Steady on. Remember what happened to the taxi.”

K glanced at me and his look was so purple with fury that I choked back my words and lit another cigarette. Then I looked out of the window at the way the bush uncurled a more vivid shade of green as the black clouds rolled on. The tree trunks were like charcoal-blackened posts in the painted red soil. Suddenly, a man emerged out of the bush with an enamel basin full of wild wood mushrooms. He had a yellow plastic fertilizer bag over the top of his head against the spitting rain. He sprang forward at the sight of our lonely car, almost into the path of our tires, and I caught the edge of his high voice, “Boss! Mushrooooms! Boss! Madam!”

I said, “Oh look, someone selling mushrooms. Should we buy some?”

Barely pausing, K hauled the car around in the road, peeled out a U-turn on the wet tarmac, and bore down on the little mushroom man. As K climbed out of the car, the man pressed back in response. K has that effect on people—a sort of don’t-even-think-about-

thinking

-about-messing-with-me look about his shoulders. But when K spoke, the neck-aching fury of late had left his voice. He sounded almost gentle and cheerful. He spoke Shona quickly, too fluently for me to follow entirely, but I understood enough to know that he asked about the man’s business and asked how things were these days.

Yes, things were hard with this government, the man agreed.

K wanted to know, How was the man’s family.

The man looked away. The smallest child had died. The mother of his children was in Malawi with her people. No, times were very hard.

And K tutted under his breath and asked the man whether he preferred Zimbabwean dollars or Zambian kwacha for his mushrooms. K pulled out a plastic bag in which we were carrying cash for our trip: a wad of Zambian kwacha, a stack of Zimbabwean dollars, and a pile of Mozambican meticals. K waved the alternatives at the man. The man responded, “Kwacha, boss. Please, boss. Zim dollar is buggered.” So K gave him the money and he didn’t haggle about the price of the mushrooms and then he put a hundred-dollar bill in the man’s shirt pocket and said, “Bonsella.”

K put the mushrooms into the tin trunk with the beer and chips and nuts and green peppers. “Tatenda, eh.”

“Tatenda, boss.”

As we were about to leave, the mushroom seller leaned into the car and pressed another bag of mushrooms onto K’s lap. “For you, boss. God go with you.”

I slumped back into my seat and closed my eyes.

I don’t think we have all the words in a single vocabulary to explain what we are or why we are. I don’t think we have the range of emotion to fully feel what someone else is feeling. I don’t think any of us can sit in judgment of another human being. We’re incomplete creatures, barely scraping by. Is it possible—from the perspective of this quickly spinning Earth and our speedy journey from crib to coffin—to know the difference between right, wrong, good, and evil? I don’t know if it’s even useful to try.

“God go with you!” the mushroom man had said, and I was grateful to him.

Because if anyone was going to be with us on this journey, it might as well be God. Especially if the alternatives were K’s demons, those loud little creatures with their party hats and whistles and tap-dancing shoes that caught in the front of the pickup and sucked up all the air.

Cow Bones II