Scribbling the Cat: Travels With an African Soldier (19 page)

Read Scribbling the Cat: Travels With an African Soldier Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Military, #General

K broke suddenly and he was sobbing hard. “I got a pot of sadza from inside. I told the guys to give me the sadza stick and I dipped it in the hot sadza and I dripped the sadza between her legs.

“I said, ‘Where are they?’ I said, ‘If you don’t tell me I’ll kill you.’

“Man, I could almost smell the fucking gooks.

“The other ous, they’re saying, ‘Hurry up, man.’

“Because, man, believe me, you don’t want to be in the middle of a fucking village when a fight breaks out. You’ll get scribbled one time. Plus you’ll scribble a hobo of women, children, babies on your way down. . . . It’s a train wreck. I wanted to get the info and get the hell out of there.

“So I reckon it’s either her—or it’s us, plus a whole village. I’m screaming at her, ‘Talk to me! If you don’t talk, I’ll dip this stick in the sadza and shove it into you.’

“She was crying, but she wouldn’t say anything.

“So I scooped up a whole spoon of hot sadza

.

. . . Oh shit! Oh shit! Why? Why did I have to do that? I had the knowledge and the skills and the ability to find the gooks. I could have

smelled

them out. All I had to do is walk out of that village and start walking in ever increasing circles and I would have found them. But I was . . . I was scared and I was so angry by then. We were all going to die because this bitch wouldn’t talk.

“That’s what I should have done. I should have walked away from her and so what? I would have been plugged. Those kids would have been slotted. Oh well. Better I die than . . .” K drew in a deep breath. “I took a spoonful of hot sadza and I shoved it into her . . . into her . . . you know? And I shoved and kept shoving and by now she was screaming, so I put more sadza in there. . . .” By now, K was talking in winded bursts.

“And she eventually spoke. She eventually told us where they were. They were close, they were hiding nearby. So we went in there, the four of us, and we killed twelve of them. Then the helicopters came and I was so busy with body bags and the adrenaline and taking care of the boys—my ous needed to get out of there, man. We were exhausted.

“And . . . and I forgot about her. I forgot about her. I had wanted to take her into hospital and get her fixed up, but I forgot. And she had run into the shateen to hide and after that we couldn’t find her.”

K’s voice was high and broken. He said, “She died two weeks after from her injuries, she had got an infection. . . .”

“Oh God,” I said, swallowing a surge of nausea.

“I didn’t need to do that to her. I was an animal. An absolute fucking savage. I had been fighting for so long by then, I had seen so much of what these guys did, I was exhausted. . . .”

And I thought, I

own

this now. This was

my

war too. I had been a small, smug white girl shouting, “We are all Rhodesians and we’ll fight through

thickanthin.

” I was every bit that woman’s murderer. Back then—during the war—I had waved encouragement at the troopies, a thin, childish arm high in the air in a salute of victory, when they dusted past us in their armored lorries with their guns to the ready.

I said, “I had no idea. . . .” But I did. I knew, without really being told out loud, what happened in the war and I knew it was as brutal and indefensible as what I had just heard from K. I just hadn’t wanted to know.

“So her family had me up on a manslaughter charge. The commanding officer said I needed to plead insanity. For three days, I had to talk to psychologists, and I have never lied so much in my life. That’s what the CO told me to do. He said I had to sound insane. So I told those stupid, waste-of-time shrinks that I needed to drink blood. That I was hungry for blood. I told them . . . lies. They’re such a bunch of wee-wees. They wrote in their books and they asked me questions.

“But they were so scared of me. They knew that if they had been in my position they might have done the same thing. They were so shit scared of being who I was.”

K wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. “Fuck,” he said softly. Then he said, almost with disgust, “It didn’t even go to trial. I got off.”

“What did they do to you then?”

“They sent me back to barracks for six months. They made me a training officer. I trained boys to be soldiers.”

Then K veered off the road and we lunged down a mild bank through the scrubby remains of goat-picked grass until the pickup rocked to a halt under the shade of a stink tree. K switched off the engine and the air sung with the sudden silence of where and who we were.

He said, “I have to go for a walk.”

“Okay.” I stared out the window at the undulating innocent land. It spread out like a stain; earth and sun and huts as far as I could see, interrupted with the odd kopje. It was a land dotted with goats intent on forage, on cattle intent on water, on birds trying to evade the cruelest part of the hot day. The bones of some long-ago-eaten cow had been left here by the side of the road and had lent a pink outline against the red soil, a barely pressed reminder of an entire beast.

We both got out of the car. K came around to me. He looked as if he had been crying with his whole body. His army green shirt was soaked down the front, his face glistened, his eyes were splintered with thin red veins. He stretched out his arms toward me and I noticed that his hands were shaking. I walked into his arms.

He put his face on my neck and breathed deeply, as if trying to breathe me into himself. I closed my eyes, and I let him rock me. Under the pungent warm shade of that deep green, leafy stink tree, I was inhaled in the embrace of a man whose anger had once spilled into something so hateful and so uncontrollable that it had killed a woman too young to have been as brave and upright and courageous as she was. She was a martyr and K and I were free. More or less free. Never free. Not if we thought about what we had done.

And then K left me, walking up into the shadow of a nearby kopje. I watched him leave and it seemed to me that the heat and fumes of his hatred danced after him. I slung down the way I had been taught as a child, African style, so that haunches hang between spread knees. It’s a stance that can be sustained for waiting-hours at a time. I pressed my back into the shade of the tree. My mouth was salty and dry. I pushed the palms of my hands into my eyes until I saw dots, but I could not erase the woman from my mind. And then I cried for a long time, until I was a film of sweat and my mouth was stringy with tears and my throat ached.

“Madam?”

I looked up.

Two children had materialized out of the sun-danced road and sidled up to the pickup. They stared at me shyly, their bellies pressed out at me in greeting.

I wiped my face and said, “Masikatii?”

“Taswera, maswerawo?” they asked.

“Taswera zvedu,” I lied.

And we all grunted in recognition of one another.

“Where are you going?” asked the taller child after a respectable pause had allowed us a decent amount of time to stare at one another.

“Mozambique,” I said, blowing my nose.

“You are one?”

“No,” I said, “we are two.” I lit a cigarette and waved it at the flies that had come to feast on my tears and sweat.

The older boy fished at his feet for a dry stalk of grass, which he put to his lips and pretended to light, in imitation of my cigarette. He eyed me sideways, hungrily, and waved his pretend cigarette blade of grass at me. “Fodya? Madam? One stick?”

I shook my head. “You’re not enough years. How old are you?”

“Ah come, mummy!” The boy laughed. “I am many years.” He pointed to his younger companion, of whom he was obviously guardian.

“No cigarettes.”

“Ah, mama.”

I stood up. “Okay. I’ll give you something to eat. I think there’s something for you.” I dug into the back of the black tin trunk. K’s green peppers, nuts, and wild mushrooms had fermented into a bubbling brown-green stew. The potato chips and beer had survived.

“Hurrah.” I emerged victorious. “Here,” I said, handing the children four packets of chips.

Then I sat with the children and they tried to pretend that they were not half starved and I tried to pretend that I could not see that this was the first food that had passed their lips for some time. I lit another cigarette. The children finished the chips and licked the packet. Then the older child lifted his eyes to mine and smiled crookedly, and he didn’t need to say anything.

I sighed. “Okay,” I said, “just quit before it kills you.” I handed him a cigarette from the packet and my own cigarette with which to light it.

The child sucked the smoke deep into his lungs and shut his eyes, a transformed smile on his lips.

The smaller child grinned up at me winningly, his lips greased with chips.

“No,” I said. “I’m certainly not giving you a bloody cigarette. So don’t even try.”

I hoped no one was at home feeding chips and cigarettes to

my

children.

WHEN K FINALLY BATTLED his way back through the bush to the car, the children had fallen in a gentle half doze next to the car and I was drinking warm beer.

I asked, “Are you okay?”

He nodded, but I could see from his jumping jaw that he was tense.

K frowned at the pickup. His look made me feel as if I should have been doing something useful with myself in his absence—as if he, in the same circumstances, would have had the vehicle gleaming inside and out by the time of my return. All I had to show for three quarters of an hour of free time was a few cigarette stompies, empty chip packets, a drained beer bottle, and two starving children.

“My friends,” I said, pointing a toe at the children.

He nodded.

I said, “Your mushrooms, green peppers, and nuts turned into mushrooms-green-pepper-and-nut wine. The kids ate all the chips.”

He said, “I’m not hungry.” He walked around the pickup and kicked the tires, and then he said, “We need petrol.”

So together we lifted a container of petrol off the back of the pickup. We made a siphon out of a used water bottle, holding it open into the lip of the tank with a licked-open penknife. I held the cut-lipped water bottle and K poured; the liquid throated down into the belly of the pickup. A great wash of the fuel splashed up my wrists and dried in an itchy, oily film.

“Sorry,” said K.

“It’s okay.”

The children roused themselves and offered to pour petrol for us. Their stringy arms would not have held anything much heavier than a very slim dream aloft for long. K’s unexpected smile surfaced. He said something in Shona and gave the children a few dollars each and they dissolved back into the bush. He picked up another twenty-liter container and began to pour that into the tank.

“I should just swallow this,” he said, watching the last of the pink stream of fuel spill down the throat of the homemade filter. “Then there’d be one less asshole in the world.”

Beware of Land Mines and Speed Guns

Nyamapanda

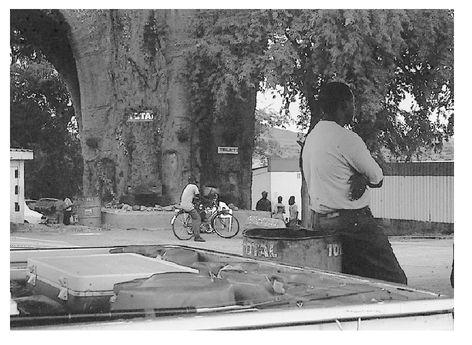

THE NYAMAPANDA BORDER post was as poetic by name as it was in real life. There was, after the feeling of stagnation that seems to have struck the rest of Zimbabwe, a sense of life and activity and vibrancy here. Bougainvillea wobbled bright blossoms over the dust-rutted road. Small vegetable gardens surged out from the tiniest and least likely patches of spare ground. Cyclists laden with bales of goods pedaled down the road. Cross-border traders, balancing loads of maize meal and soybeans and cooking oil on their heads, haggled loudly in the streets. A herd of schoolchildren in tatty blue uniforms came tripping past, barefoot and exuberant, kicking up dust as they walked.

The fuel station (the only place in the whole of Zimbabwe where we were able to find petrol) held a TOTAL sign in the wrinkled, pink-gray skin of an elephantine baobab tree. Next to that sign, also nailed to the enormous tree, was a marker advertising TOILETS, although, when I investigated, it seemed that the long drops intended to serve that purpose had long since received all the human waste they were designed to contain. I went back to the pickup.

While we filled up our empty containers with petrol, a very old blind woman (she had shrunk to the size of a child and her hair had turned vivid yellow) was led up to the car by her helper (a young, bored-looking boy). Without any difficulty, she extracted money from K, who said, “The Almighty is very specific about this.” He added, “Zambian kwacha too.”

We had to bribe our way out of Zimbabwe because of the extra fuel we were carrying. Zimbabwe’s fuel crisis had become a national emergency, so it was illegal to carry more than a full tank of fuel out of the country’s borders—in this area of vast distances and few amenities, it was not only inconvenient but potentially dangerous to have only one tank of petrol at hand. While K negotiated with the customs official (who was threatening to send us back to Harare for police clearance), I sat on the back of the pickup and kept a wary eye on our belongings.

A lorry carrying a load of fertilizer was parked at the border gate, which opened into no-man’s-land and from there into Mozambique. I watched as a group of six or seven young men unhurriedly pulled back the tarpaulin that covered the load, sliced several bags, and filled buckets with the spilling white product.