Secrets at Sea (2 page)

Authors: Richard Peck

Â

WE ARE MICE, and as Mother used to say, we are among the very First Families of the land. We were here before the squirrels. The squirrels came for the acorns. We

sold

them the acorns.

sold

them the acorns.

And we were here ages before the Dutch came up this river. Ages. We made room for them, of course. They were well-known for their cheesesâEdam, Goudaâthese Dutch people. And they built good strong stone houses, gabled and stout to keep winter out.

We came indoors then, in through the Dutch doors. We came in from the cold and were field mice no more. We hardly needed our winter coats once we'd settled among the Dutchâbehind their walls, below their floors, beside the Dutch oven. There were crickets on their hearths. But we were not far behind, gray as the shadows, between one loose brick and another. Here we hollowed out our homes. Just a whisker away, only a nibble from the cheese in their traps.

We wear clothes only in our quarters, here within the walls.

When they were Dutch upstairs, we were Dutch down here. We learned their tongue. We are excellent at languages. Excellent. And we took their names. I had an ancestress with a long gray tail and eyes as beady as mine, and her name was Katinka Van Tassel. How Dutch can you get?

After the Dutch came the English. Yes, the English, and very high and mighty. They brought taxation without representation. Teaâoceans of teaâand a ridiculous nursery rhyme called “Hickory Dickory Dock.”

The English built a grander house around our Dutch cottage. And they cut the trees for a sunset view down to the river. Though water in any form is not a happy subject with us mice. The best reason for a river I can think of is for drowning cats.

But all of this was long ago, and our Upstairs humans are the Cranstons now, from Cleveland. And so we too are Cranstons, we mice, though of a longer tradition. We have the background they lack.

So there you have the history of our Hudson River Valley. A rodent view, naturally, and the short version.

Â

“THEN I'D HATE to hear the long version,” as my sister Louise always says. But that is Louise all over: snippy and skittery, though always first with the news, whether she understands a word of it or not.

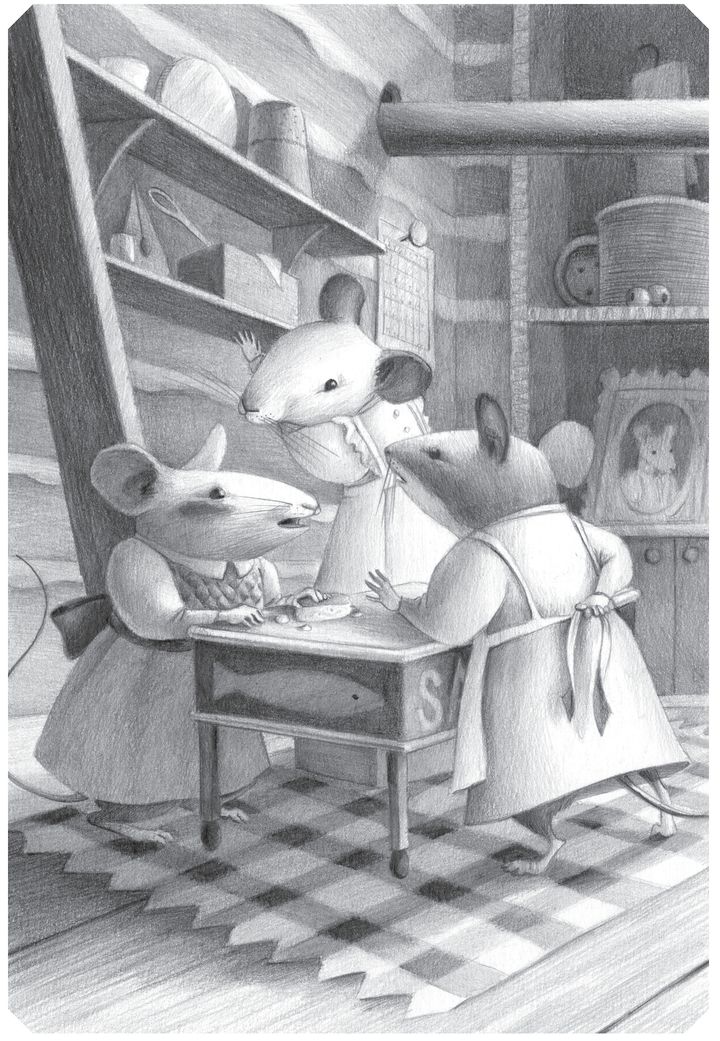

We three were still there around the crumbed table, dizzy with what she'd heard from Upstairs. Louise was fastening her skirt at the waist, though she has no waist. In the quiet you could hear something like thunder from high in the house.

It must have been Olive and Camilla and Mrs. Cranston running into each other as they tried on all their hats. It was the thunder before the skies opened to wash our old lives away.

Then our brother, Lamont, stormed into this thoughtful moment. Lamontâhome in the middle of the day! Our hearts sank. Lamontâunderfoot and everywhere you turned. His lashing tail swept two or three items off the shelves and the cheeseboard off the table.

Being a boy, he sowed the seeds of destruction wherever he was. And he was home now, hungry for his lunch because mouse school had closed at noon and all the scholars sent home. A cat had been sighted in the vicinity.

CHAPTER TWO

Skitter and Jitter

A

LL MICE HAVE sisters, and you have met mine. I am Helena, the oldest. But I was once the mouse in the middle when it came to sisters. There were two older: Vicky and Alice. But they are no longer with us and can play no part in the great adventure coming in our lives.

LL MICE HAVE sisters, and you have met mine. I am Helena, the oldest. But I was once the mouse in the middle when it came to sisters. There were two older: Vicky and Alice. But they are no longer with us and can play no part in the great adventure coming in our lives.

Theirs is a painful story that we need not go into just yet. Mother is no longer with us either, which is part of the same sad story. As you may imagine, it involves water.

But now we needed to settle Lamont to his lunch, or he'd pester us to death. Yesterday was baking day for the Cranstons' cook, Mrs. Flint. She has a heavy hand for pastry, but she bakes a passable corn bread. And a simple farmhouse cheese is not beyond her.

We lived in the kitchen wall, and our back door was a crack in the plaster nobody had noticed since the days of the Dutch. It opened behind the big black iron stove, just to the left of the mousetrap.

Mrs. Flint was an indifferent cook, but there were two good things about her. Her eyesight was poor, and she did not live in. Either she couldn't see us or she wasn't there. So we were pretty free to browse her kitchen for our meals.

And you may take my word for it: We had every right to our share. We were here first. Besides, mice can come in very handy to humans. Times come when mice more than pay their way. Just such a time was coming. Read on.

But now it was time to feed Lamont his lunch of corn bread crumbled into a thimble of milk. We tied a napkin around his neck, for all the good it will do.

“Do not bolt your food, Lamont.” I stood over him. Somebody has to. “Those teeth are for chewing. Think of the many mice who must forage for their food, Lamont. Mice who would be glad to be sitting at your place.”

Lamont's stomach grumbled unpleasantly as he tore into his corn bread. His stomach is a bottomless pit.

Then this bothersome boy looked up, twitched his whiskers at us, and said, “Will they be taking Mrs. Flint with them when they sail for Europe? The Upstairs Cranstons?”

I slumped. Louise stared. At school Lamont learned everything but his lessons. How provoking that he'd heard the news as soon as we had. Maybe before.

“Sail?

Sail?

” Beatrice clutched her throat. “Is Europe across water?”

Sail?

” Beatrice clutched her throat. “Is Europe across water?”

We were in a tizzy then until Lamont escaped out into his free afternoon. We barely got the napkin off him. He'd dropped down to all fours and scampered for the front door. He was half wild, was Lamont. Boys are.

“Keep one eye on the sky, Lamont,” Louise called after him. Because any number of things can swoop down on a mouse. Things with wings and talons. Beaks. Especially upon a mouse who does not think. “And remember who lives in the barn!”

“And in the haystack,” I added. Louise and I exchanged glances. What lived in the haystack didn't bear thinking about.

“Water?” Beatrice said in a strangled voice. “Europe is across water?”

Â

CALM FINALLY SETTLED as we drew up chairs for

our

lunch, and a spot of coffee afterward. Mrs. Flint always left a pan of breakfast coffee at the back of the stove. We had a cunning little dipper we could send down into the pan on a length of picture wire.

our

lunch, and a spot of coffee afterward. Mrs. Flint always left a pan of breakfast coffee at the back of the stove. We had a cunning little dipper we could send down into the pan on a length of picture wire.

We lingered over our coffee as the kitchen clocks struck, and then again. We are not good about time, we mice. For us, time always seems to be running out.

Then the front doorbell sounded through the house. We jumped.

Hardly anybody ever came to call. Mrs. Cranston and Camilla and Olive sat through long afternoons in their second-best clothes. They sat sideways on the settee because of their bustles, waiting for visitors who never came. They sat through whole dreary afternoons, corseted and alone.

The doorbell rang again.

“I'll go,” said Louise, out of her chair, and her skirt. She could never wait to stick her nose into whatever might be happening.

“Curiosity killed the cat,” I called out to her. This is one of my favorite sayings. Beatrice would have scurried after her if I hadn't given her one of my looks.

We sat on at the table, Beatrice and I. Mice hear better than humans. We should, with these ears. But only mere mumbling murmured down the house along the ancient trail in the walls blazed by mice before our time. We are a very old family, as I have said.

I kept Beatrice busy. Idle hands are the devil's workshop. Yes, we have hands. There is talk of paws and claws, but look closer. We have hands, very skilled. I can thread a needle while you're looking for the eye. I sew a fine seam, and Beatrice was learning. I tried to teach her what she'd need to know.

The kitchen clock struck another afternoon hour away. Which hour I do not know. We are not good with time. Through the wall Mrs. Flint's kettle sang. She was putting cups on a tray to send upstairs. I was beginning to wonder where Lamont was. I am the oldest, and so the worries reach me first.

But at long last a sound of skittering came from far up our front passage. Then nearer skittering and gasping mouse breath. We set aside our needlework, Beatrice and I, as Louise burst in upon us. Somehow it seemed that Louise was either just coming or just going. It was hard for her to settle.

“You'll never guessâ”

“Skirt, Louise,” I said. Beatrice handed it to her.

Louise stepped into her skirt. “Is there any of that coffee left? I'm dry as aâ”

“You're keyed up enough without more coffee, Louise. Just watching you makes us jittery,” I said. “You skitter and we jitter. Sit down and tell us what we will never guess.”

She drew up a chair. “Where shall I start?”

“Who came to call?”

“Oh yes. A Mrs. Minturn.” Louise made big eyes at us.

“Not a local family,” I said.

“No, indeed. She came up from the city.” Louise tapped the table. “On the

train.

”

train.

”

“Ah, if she is from New York City, she must be selling something,” I said. “Everything is for sale in New York City.”

“They showed her their hats, and she said they wouldn't do,” Louise said.

“Was she selling hats?” Beatrice wondered.

“I'm not sure,” Louise said. “She was wearing an awful old shovel bonnet herself. It was rusty with age, and so was she. And, oh my, her veils were torn.”

“You seemed to get a good view of her, Louise,” I remarked.

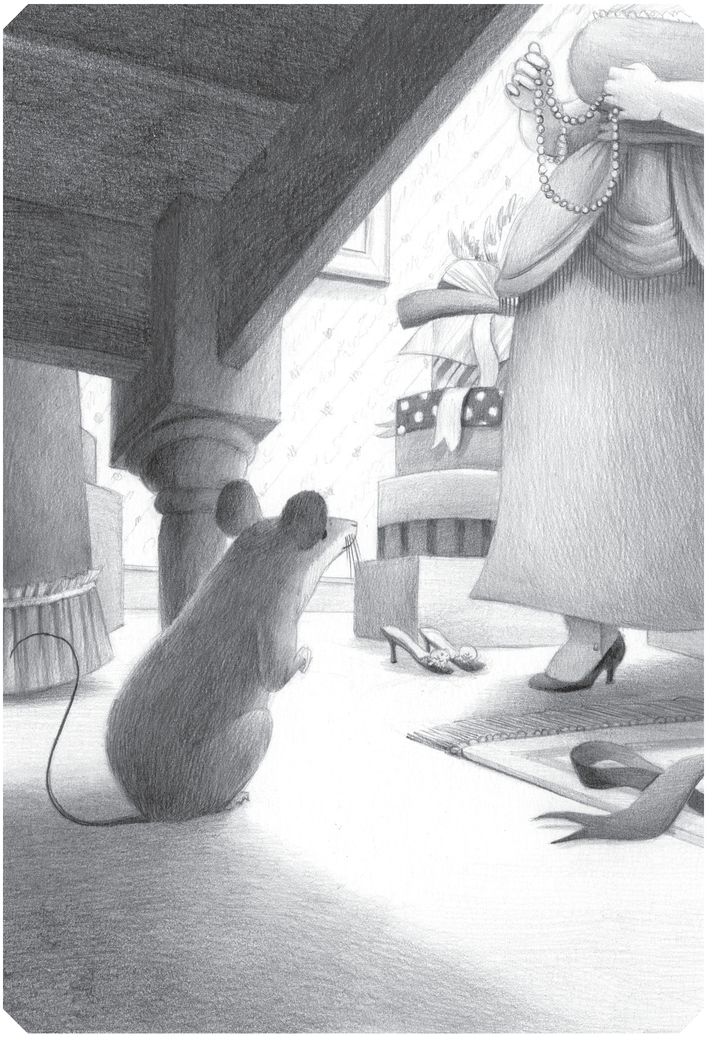

“I was under that marble-topped table by the horsehair settee, right at their feet. But they wouldn't have noticed me if I'd been sending up flâ”

“What was this woman's business, Louise? This sounds like business to me.”

“Well, she was very businesslike,” Louise said. “But I'm not sure. She told them how they better dress if they were going to Europe. She said that bustles are over. Bustles are completely over in Europe. Nobody even remembers bustles.”

“Then what?”

Louise pressed a finger to her cheek. “Oh yes, then she had Olive walk up and down the room. Up and down. Up and down.”

“What for?”

“To see how Olive moved,” Louise explained.

“How did Olive do?” Beatrice asked.

“Not very well. She ran into things and caught her toe in the rug. You know how Olive is around her mother. And Mrs. Cranston was jumpy as a cat. I was right there by one of her shoes, and she kept tapping it. She very nearly mashed me into the carpet. âWe must give Olive Her Chance,' she kept saying. Over and over like she does.”

“How did all this end, Louise?” I asked, because she was going on forever. “Put it in a nutshell.”

“I was right there by one of her shoes.”

“Money,” Louise said.

“Money?” said Beatrice.

Louise nodded. “Mrs. Minturn said it would take money to unlock the doors of Europe. Nobody in Europe is interested in poor Americans. No young man is. Evidently they have enough poor people of their own.”

We pondered all this. “Then what happened?” Beatrice said.

“Well, Mrs. Minturn just sat there with her hands in a bunch until Mrs. Cranston reached down for her reticule, which was just a whisker away from me. She handed her some money.”

“How much?” Beatrice inquired.

“Well, how would I know?” Louise said. “She didn't show it to

me.

But it was quite a wad. What do you think this all means, Helena?”

me.

But it was quite a wad. What do you think this all means, Helena?”

The four eyes of my sisters fell upon me. But I was spared answering. Lamont exploded out of the front passage and was all over us. Lamontâflinging himself on the floor, right there on the rag rug. His eyes rolled like a mad horse. His underbelly showed pale as paper through his fur.

Other books

If I Die by Rachel Vincent

Seven for a Secret by Mary Reed, Eric Mayer

Judgment Day -03 by Arthur Bradley

Dark Before the Rising Sun by Laurie McBain

Marco's Redemption by Lynda Chance

American Woman by Susan Choi

Sophie's World: A Novel About the History of Philosophy by Jostein Gaarder

Monkey Mayhem by Bindi Irwin

Granted: A Family for Baby by Grace, Carol