Secrets at Sea (8 page)

Authors: Richard Peck

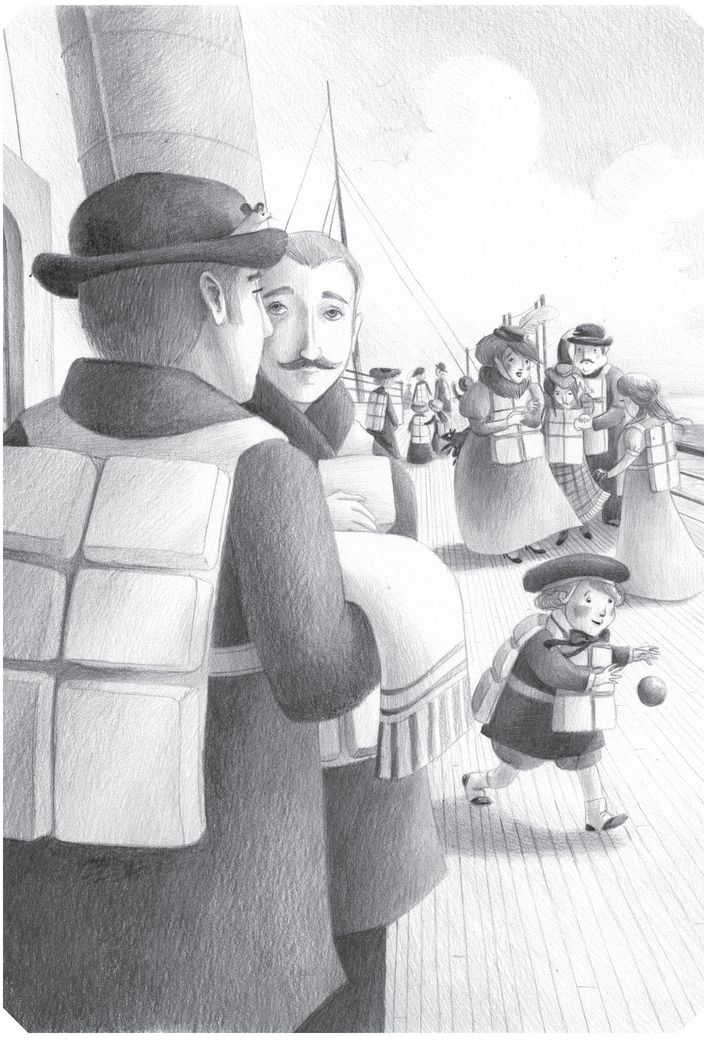

Mice rarely laugh, but I was tempted. Over their heaviest outdoor clothes they wore great, bulky, bulging things strapped around them. Mr. Cranston, a large, shapeless man anyway, in a bowler hat and his windowpane plaid greatcoat under his life preserver. Mrs. Cranston, bigger than he, in a gigantic feathered hat, her squirrel-skin cloak, and over that her life preserver, stretched to its limits.

“She'd sink like a stone,” Louise muttered in my ear. “That life preserver wouldn't float her

hat.

”

hat.

”

Olive looked wretched. She'd anchored her hat with a pea-green veil that matched her face. She swayed sickeningly. Camilla looked the best of them as she always did. But a life preserver is flattering on nobody. Law of the Sea indeed. They looked ridiculous.

Mrs. Cranston fussed over them all in that way she has, but they were heading off along the corridor to the open deck. I was just ready to duck back inside the cabin when I got a shock more surprising than I can tell you. Beatrice and I were cheek by jowl under the door when out of the blue she blurted, “Well, I for one am not going to be left behind! The Upstairs Cranstons are heading for the lifeboat! I'm going too. We are their mice. Our fates are intertwined with theirs!”

I was so stunned by this outburst I could hardly utter. “Beatrice, it's only a lifeboat drill. An

exercise.

”

exercise.

”

“You don't know that,” Beatrice babbled right in my ear. “It could be the real thing! Besides, I bet ships have sunk before during lifeboat drills. You know nothing about it. You don't know everything, Helena.”

She was hysterical. I would have slapped her, but there wasn't room. “Beatrice, they are making for the open deck,” I explained. “It will be miles and miles of ocean in every direction. You'll be petrified. It's

water,

Beatrice.”

water,

Beatrice.”

“I don't care,” she said. “I want to see that lifeboat with my own eyes. You never know if we might need it!”

And with that, she squirmed under the door and shot off down the corridor before Louise or I could think.

We watched round-eyed as she bore down upon the dawdling Upstairs Cranstons. There's nothing wrong with our eyesight, and we saw her take a flying leap at the dangling tails of Mrs. Cranston's squirrel cape. She was swallowed up by squirrel tails and distance.

We were shocked witless. Our chins would have been on the floor except they already were. Then into my other ear Louise muttered, “She might have a point.”

“What?”

“She might. I wouldn't mind knowing where the lifeboat is. Besides, it didn't take Beatrice long to infest Mrs. Cranston's fur cape. What will she get up to next, do you suppose?”

Then we were both squirming under the door and flying along the corridor. Our feet hardly grazed carpet. Louise was in the lead. I tried to keep up, but I'd had so little sleep. You try spending the night on a mattress of hatpins and pearls.

I could see Louise closing the gap between herself and the sweeping skirts of Camilla's coatâa gabardine duster.

And that's all I saw.

Just ahead of me a cabin door opened. Two gigantic human figures stepped outâmen. Right in my path. The whole world before me was a dark herringbone tweed. I tried to stop. I tried my best. I did a complete somersault and went whiskers over teacup, ending up on my back, facing the wrong way.

Now panic gripped me. I scrambled up. But I could see nothing of the Upstairs Cranstons or Louise. I could see nothing but gentlemen's boots and trouser legs. I leaped onto the trouser leg of the second man. Pure panic, and not a good place to be if he followed the other man off down the corridor.

But above me he spoke. “Oh, sir, I quite forgot your lap robe,” he said. “You may require it on the open deck.”

“Very well, Plunkett,” said the other man.

With that, heâPlunkettâturned back to the cabin door. He strode inside, and I swung like a bell from his trouser without the sense to drop off. Besides, he could have mashed me into the carpet

like that.

like that.

The cabin smelled of bay rum aftershave lotion. The lap robe was a blanket in the ship's colors, with fringe. He reached for it. I reached for the hem of his overcoat. Then I was traveling. You can get your nails into herringbone tweed.

I swarmed up him, over the life preserver, spongy with all its milkweed inside. Now I was on one of his tweedy shoulders. If he'd glanced sideways, we'd have been eye to eye. This was no place to tarry.

I was right by Plunkett's ear, in the shadow of his bowler hat. I looked up. A short leap and a little luck, and I could swing up into his hat brim. Panic propelled me. There are forces stronger than gravity.

Up I swung and lit in his brim. It was a curly trough around the crown of his hat. I settled in, very supple. Of course, I was six feet off the deck on the head of a humanâa perfect stranger and probably foreign. What a sudden place the world is.

Out in the corridor my human kept a step behind the other man. Now we were on stairs. Now a heavy door swung and a sharp gust of damp ocean air hit us. Plunkett's enormous human hand came up to grab the brim of the hat, trapping one of my whiskers.

I hadn't thought of this, of course. I hadn't thought at all. What if this bowler hat blew off his head? I lay in the trough of the brim, paralyzed. What did I fear more, those four fingers, big as giant sausages, gripping the brim and my whisker, or sailing off his head and out to sea?

It wasn't a long walk to our lifeboat. By now I'd figured out that I was in the hat brim of a servant. Ladies travel with their maids, as everybody knows. I supposed gentlemen traveled with their valets, or whatever persons like Plunkett were called.

Humans milled just below me. I hazarded a look over the brim. There upon the crowded deck was an ancient human in a flat cap and many lap robes. In his life preserver he looked like a beached walrus. He slumped in a wheelchair pushed by his valet. The Marquess of Tilbury, no doubt, who had to be fed by hand.

Then out of the milling throng came another pair of quite a different kind, though also English. Striding along the deck was a woman, treetop-tall with the face of a disapproving prune. On her head a starched cap, with veils flowing down her back. A very superior servant, no doubt. A nanny, in fact, because attached to one of her hands was a small boy, in a sailor cap with ribbons. Well, not small, but about five years old in human terms. He carried a rubber ball that he wouldn't be parted with even for boat drill. In fact, he looked like a rubber ball himself, wearing a life preserver.

His small blue eyes were nearly lost above his enormous pink cheeks. He wore a sailor suit to go with his cap. His shoes buttoned up his fat legs.

Here was undoubtedly little Lord Sandown, who would one day be the Earl of Clovelly. He looked like he might be a handful. But the nanny gave him a sharp jerk to keep him near her serge skirts.

I chanced a look beyond him, and there was . . . the sea. More water than I knew there was. Gray and choppy. A world of water. The deck rose and fell. The lifeboats swung from their davits. I hoped in my heart we'd never have to get in one of those things.

Whistles shrilled. Uniformed men tried their best to round up the humans to stand near their lifeboats and be counted. But it was like herding you-know-whats.

My two human gentlemen stood a little apart from the crowd. The other gentleman spoke. “I shall not be needing the lap robe, Plunkett, on such a pleasant day at sea.”

He was quite nice-looking for a human, and young in human years.

“Very good, Lord Peter,” said my humanâPlunkett.

I nearly forgot my fear, there in the brim, staring at sky and trailing smoke. Lord Peter? Could this be the Lord Peter Henslowe the Duchess of Cheddar Gorge had named at dinner last night? Twenty-four years old and good-looking and hard to catch?

What strange fate had brought me so near him, I wondered, in all this multitude of humans?

I chanced another look. Beyond Lord Peter's fine profile I saw all the Upstairs Cranstons in a clump. Sea breeze whipped Mrs. Cranston's hat into a frenzy of feathers. I scanned her for Beatrice. But no saucy, beady eyes appeared to peer out of her squirrel pelts. And while Louise must have been someplace on Camilla's person, I couldn't see where.

I chanced another look.

As I watched, Olive detached herself from the family and staggered on the slanting deck to the railing. There she was stupendously sick over the side of the ship. Oh my, she was sick. It went on forever. I hoped there were no people leaning on the rails of lower decks.

Her family rushed to her aid, to keep her from pitching over in that space between the rail and the lifeboat.

“Let me go!” Olive announced. “I'm dying anyway.” She threw her head over the railing yet again.

“Olive has not found her sea legs!” Mrs. Cranston boomed to the world. “Send for the doctor!”

“Plunkett,” Lord Peter said quietly, “give the young lady my lap robe.”

Plunkett and I surged forward. I cringed in his brim. Now Olive was sagging in Mr. Cranston's big fists. She hung there, pea-green, with her damp veils plastered against her preserver and her hat over one ear. She wasn't dying, but she was willing. And she looked her absolute worst.

“Sir, for the young lady,” said Plunkett, holding out the lap robe for Olive's heaving shoulders.

“Good of you,” Mr. Cranston rumbled. Mrs. Cranston loomed up to wrap Olive in the lap robe.

I should have seen this coming. I should have thought ahead. Why didn't I? In the presence of a lady, even Mrs. Cranston, Plunkett . . . reached up to take off his hat to her.

The giant sausage fingers appeared again, to grip the brim. Off came the hat. My world tipped and tilted. I skidded halfway round the trough. Then I was in the air, turning there above the sea and the lifeboat and the slanting deck. I seemed to soar somehow. I scudded like an autumn leaf, grappling with thin air. I lit directly on the ship's railing. We always land on our feet, but another inch in the other direction, and I'd have gone straight into the sea and fed myself to the fishes. Water is not a happy subject with us mice.

The air was knocked out of me. But I gripped the railing, fighting for breath, pulling myself together.

Honestly, what a day.

A murmur went up. I had appeared from nowhere. Now I was in plain sight where you never want to be. Dozens of humans were astonished to see me there. Scores of humans. I felt their eyes. “Eeeek,” said several.

“Floyd!” Mrs. Cranston clutched her husband and shrieked. “The rats are deserting the ship. We must be sinking!”

“Fiddlesticks, Flora,” roared Mr. Cranston. Olive still sagged in his hands. “It's only a mouse.”

“Oh, Mousie!” Camilla exclaimed.

It was time I made tracks. But the railing was slick with polish. The English spit and polish. I scrabbled and skidded. I slipped sideways. Sea breeze caught my ears. My tail was all over the place. I might yet pitch into the unforgiving sea. I looked in that direction, into the lifeboat.

I froze. There on a bench, sitting in orderly rows, were easily twenty mouse boys. Mouse Scouts. Standing over them was Nigel, taking roll. They too were having lifeboat drill. They all looked up in surprise at me, though nothing surprises Nigel.

I didn't pick out Lamont from among them. I simply didn't have the time. I ran for my life.

CHAPTER NINE

A Royal Command

P

URE PANIC HAD sped me out of Camilla's cabin. Instinct led me back. Now I lay panting under her bed, planning never to budge until we docked. Exhausted. My head rattled with all I'd been throughâthe tipping hat brim, the endless sea, all those humans. From the cabin next door came Olive's piteous moans and a deep voice. The doctor must have arrived.

URE PANIC HAD sped me out of Camilla's cabin. Instinct led me back. Now I lay panting under her bed, planning never to budge until we docked. Exhausted. My head rattled with all I'd been throughâthe tipping hat brim, the endless sea, all those humans. From the cabin next door came Olive's piteous moans and a deep voice. The doctor must have arrived.

Though I didn't mean to blink until Beatrice and Louise were back, I dozed off and dreamed that I'd missed the railing and was feeding myself to the fishes. A dream of time running out.

Voices brought me to the surface. “Oh for pity's sake, Helena. Napping in the middle of the day?”

Louise was back, and with her Beatrice. Beatrice sneezed.

“That squirrel cape of Mrs. Cranston's is disgusting,” she said. “It reeks of mothballs and camphor and . . . squirrel. I like to have suffocated.”

I gathered myself up and did something with my tail. I had hardly slept. “But what about the

sea,

Beatrice?” I said with my usual concern. “Weren't you terrified?”

sea,

Beatrice?” I said with my usual concern. “Weren't you terrified?”

“I never really saw it,” said the provoking girl. “I couldn't fight my way out of all those dead squirrels.” Beatrice pondered. “Oh, I did just manage one peek. I saw you on the railing, Helena. Honestly, what were you thinking?”

Other books

Owned by B.L. Wilde, Jo Matthews

The Battle by Barbero, Alessandro

El hijo de Tarzán by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Power of a Woman by Barbara Taylor Bradford

A Good Rake is Hard to Find by Manda Collins

Rimfire Bride by Sara Luck

Destined for Time by Stacie Simpson

The Romanov Legacy by Jenni Wiltz

Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick by Lawrence Sutin