Self Condemned (2 page)

BY ALLAN PERO

W

yndham Lewis has always been a flashpoint of controversy. A Modernist Renaissance Man, he is as famous for his brisk, whiplash line as he is for his satirical, crackling prose. In addition to his achievements as a visual artist, he was a novelist, satirist, philosopher, polemicist, poet, and art critic. He was born in Canada at Amherst, Nova Scotia, on November 18, 1882 (the same year as two of his contemporaries, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf). His father, Charles Lewis, was a wealthy ne’er-do-well who fought on the Union side in the American Civil War. One of the interesting features of the Lewis family is that several of its branches extended from the United States into French Canada. Charles’s brother, William, was a Montreal wine merchant, for whom Charles worked for a time. Lewis’s mother, Anne, was British. Their marriage wasn’t a happy one. After a brief period spent in Canada, the Lewises moved to England, and their young son, then called Percy, attended Rugby (the British preparatory school), and later won a scholarship at the Slade School of Art. These funds came in handy, since Charles Lewis had spent much of the family’s money, having run off with the maid some years earlier. Anne Lewis had been left in straitened circumstances to raise the boy alone.

Lewis quit the Slade in 1902, and for about six years spent his time travelling, studying, and painting in France, Spain, and Germany. Fluent in French, he attended lectures at the Collège de France given by Henri Bergson, a French philosopher then very much in vogue. During this time, Lewis became fascinated by the various artistic modernisms then beginning to emerge — among them, Cubism and Futurism. When he returned to England, he began to publish some stories based on his Continental experiences, which were eventually collected under the title

The Wild Body

. Along with Ezra Pound, Lewis has the distinction of being the co-founder of Vorticism, the only avant-garde group Britain has ever produced. The Vorticist movement’s manifesto

BLAST

, which published, among others, T.S. Eliot, Ford Madox Ford, and Rebecca West, appeared a few months prior to the beginning of the First World War. Lewis was himself caught up in the conflict, first as a gunner and bombardier, and was later fortunate enough to receive a commission as an official war artist for the Canadian government in 1917. He narrowly escaped death several times; the devastation of the war prompted him to develop a larger conceptual framework for thinking about art, culture, and politics in what he several years earlier had called the “Melodrama of Modernity.” His first novel,

Tarr

, a sharp, Dostoevskian critique of the bourgeois-bohemian set in Paris, appeared in 1918.

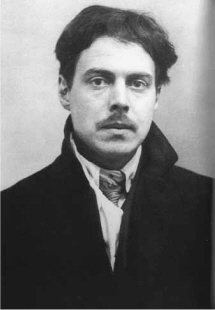

Wyndham Lewis as a

second lieutenant in the

British Army during the

First World War.

One of the results of the Great War was that it effectively killed the Vorticist movement. By 1922, Lewis’s own art production had begun to slow down as he became more engaged with the task of writing. He spent several years researching in the British Museum and started publishing, between 1926 and 1931, an astonishing number of prose texts:

The Wild Body

,

The

Art of Being Ruled

,

The Lion and the Fox

,

Time and Western Man

,

The Childermass

,

The Apes of God, Paleface

,

The Doom of Youth

, as well as the sledgehammer title

The Diabolical Principle and the

Dithyrambic Spectator

. Together these books come to several thousand daunting but fascinating pages. The imaginative scope of these volumes, comprising fiction, philosophy, political theory, and art and literary criticism, offers trenchant analyses of culture and everyday life. They are a testament not only to the range of his thinking and reading but also to his titanic energy. Lewis’s persona became that of the Enemy, who would suddenly appear on the scene, provoking critique, laughter, and acrimony. As you might surmise, though he counted people such as Pound, Eliot, Joyce, Augustus John, Rebecca West, Marshall McLuhan, A.Y. Jackson, the novelist Naomi Mitchison, and the “Queen of Bohemia,” London painter Nina Hamnett, among his friends, he also made several enemies — like Virginia Woolf, the artist and critic Roger Fry, Lytton Strachey, the Sitwells — but these antagonisms were sometimes taken more seriously by the public than by the participants (not that they didn’t feel the sting of one another’s barbs). Lewis once said of Edith Sitwell: “We are two good old enemies, Edith and I,

inseparables

in fact. I do not think I should be exaggerating if I described myself as Miss Edith Sitwell’s

favourite

enemy” (

Blasting and Bombardiering

, 91). He was right. She devoted an entire chapter to venting loving spleen about him in her autobiography,

Taken Care Of

, seven years after his death in March 1957.

Lewis’s reflections on the development of the Enemy persona surface in a brief 1932 article entitled “What It Feels Like to Be an Enemy.” His answer revolves upon the idea of intimacy: to be an Enemy is “Much the same as a Friend — a very

intimate

friend, who has forgotten why or how he ever came to begin the relationship” (

Wyndham Lewis on Art

, 266). In caricaturing his persona as the Enemy, Lewis ironically exploits the cultural and political implications of this confusion of the two terms, even as he acknowledges (with puncturing tongue-in-cheek) that his actions as the Enemy are also a self-mocking study in urban paranoia.

For example, his use of modern technology (“the telephone is an important weapon in the armoury of an ‘Enemy’”) is central to his ludic reign of terror:

After breakfast, for instance (a little raw meat, a couple of blood-oranges, a stick of ginger, and a shot of Vodka — to make one see Red) I make a habit of springing ... to the telephone book. This I open quite at chance, and ring up the first number upon which my eye has lighted. When I am put through, I violently abuse for five minutes the man, or woman of course (there is no romantic nonsense about the sex of people with an Enemy worth his salt), who answers the call. This gets you into the proper mood for the day. [

Wyndham Lewis on Art

, 267]

These fictional telephonic ambushes reveal to us our uncanny relation to the telephone; we have installed, at our own expense, hailing devices that simultaneously preserve and compromise both our anonymity and our sense of identity. His telephone calls alert us to our subjection; the disembodied voice, booming with malevolence and mockery, performs the subversive role of conscience. In the role of caller, his is the alien voice that signals to us our own uncanny nature. Lewis’s pranks are meant to show us that the ringing telephone doesn’t necessarily ensure and reaffirm who we are, or that we’re important. Instead, he playfully takes us to task for our compliance, for our complacent pleasure in following the rituals of subjection that lurk behind phrases like “Sorry, I’ve got to take this.”

In this regard, it’s no wonder that his engagement with media and technology would influence the thought of Marshall McLuhan. Lewis and McLuhan met in Windsor in the 1940s (where Lewis had moved after his unhappy sojourn in Toronto), when the latter was then starting his career at St. Louis University. As an accomplished and ingenious lecturer at Assumption College (then part of the University of Western Ontario, and now the University of Windsor), Lewis played a role in securing McLuhan’s two-year appointment to the faculty. The impact of Lewis’s thought on McLuhan’s work is obvious: McLuhan’s books are peppered with quotes and references to Lewis’s works. Apart from his analyses of advertising, temporality, and visual media, Lewis’s book

America and Cosmic Man

contains the seed of one of McLuhan’s most famous concepts: the global village.

At thirty-seven years old,

Wyndham Lewis cut a

dashing figure.

But any discussion of Wyndham Lewis must always return to a particular problem — his notorious “flirtation” with fascism. Indeed, for many people, Lewis’s relationship to fascism was much more than mere flirtation — it was a fine romance. At least, a romance in the sense that it is assumed that Lewis was happily in love with fascism and never questioned it or its aims.Yet I would suggest the opposite; his relationship to fascism was informed by nothing

but

questions. Even a quick glance through his political books of the 1930s reveals maddeningly contradictory stances. Fascism is variously described in these works as a problem, a cult, an alternative, a pose, a nostalgic return to classical imperialism, a tool for peace, and a product of war. What do we make of this panoply of contradiction? Rather than look upon it as mere “inconsistency,” I contend that we should think about its implications. At several moments he seems to suggest a kind of approval of fascism, even as he elsewhere (often in the same text) criticizes and satirizes its politics. Suddenly, he will bizarrely declare himself on the political left, while at the same time inveigh against the brutalities of Stalinism in the Soviet Union (which in the 1930s was a very unpopular opinion among many leftists).

Lewis’s response to fascism assumed this trajectory: (1) a qualified, contradictory approval, followed by (2) a period of hectic activity in which he isn’t so much defending the “truth” of fascism as he is trying to contain (and explain) the increasing number of political fires set by it in Europe in the 1930s; (3) that in attempting to retain fascist Germany as part of Europe’s political landscape, he is working through his uncertain identification with Hitler by critiquing Europe’s failure to live up to its own egalitarian principles; (4) that as a veteran, he is genuinely horrified by the prospect of another world war; and (5) much of the last two decades of his creative and intellectual thought are devoted to the question: “Why did I not

see

what fascism is?” He would later dismiss his political writing of that period as “ill-judged, redundant, harmful of course to me personally, and of no value to anyone else” (

Rude Assignment

, 224). How many writers or political commentators would dare say such a thing about their own work? Not many.

After a series of trips to Europe in the 1930s, Lewis changed his political stance radically. Witnessing first-hand the effects of Adolf Hitler’s domestic policies, and the horrifying conditions Jewish people were forced to endure, Lewis confronted the important difference between the myopia of political abstraction and the brute clarity of political fact. The question of his political blindness (sometimes projected onto others) is putatively asked and answered in series of books, fiction and non-fiction alike:

The

Hitler Cult and How It Will End

,

Anglosaxony: A League That Works

,

Rude Assignment

,

The Writer and the Absolute

, and

Self Condemned

.

This reprint of

Self Condemned

is based upon the first edition published by Methuen in 1954, three years after Lewis went blind, and three years before his death (even then a period of enormous productivity in which he produced some of his best work).

Self Condemned

is in part based upon the experiences of Lewis and his wife, Gladys Anne (always called Froanna), who left for Canada the day before war was declared in September 1939. Although he had predicted (for once, rightly) in

The Hitler

Cult

(1939) that the Second World War would last six years, he never intended to remain in North America for the duration of the fighting. The trip was expected to be an opportunity to pick up portrait commissions from wealthy Americans and Canadians. Regrettably, very few actual commissions materialized, though he did paint Eleanor Martin, the mother of former Prime Minister Paul Martin. A recurring cycle of bad luck, debt, cash-flow problems, and social isolation all contributed to the Lewises’ largely unhappy stay in the long-gone Tudor Hotel on Sherbourne Street in Toronto — a dismal refuge that Lewis at the time generalized as his “Tudor period” (

Letters

, 311). Strangely, he took very little advantage of his family connections in Montreal, which was, of course, a lively cultural centre even in the 1940s. Indeed, some Montreal painters and writers — among them, Jori Smith, Marion Scott, John Lyman, and Prudence Heward — were readers of his work. Lewis made several notorious pronouncements about Canada and Toronto of the 1940s, which rankle or delight, depending on one’s sensibility. He referred to Canada as “a sanctimonious icebox,” and offered this diagnosis of Toronto the Good: “‘Methodism and Money’ in this city have produced a sort of hell of dullness” (

Letters

, 309, 327).