Self Condemned (3 page)

But it would be a mistake to confuse the novel with autobiography. René Harding, the main character, is not Wyndham Lewis. Nor is Hester Lewis’s wife, Froanna. The differences are crucial. In the novel, René Harding, a professor of modern history, decides to renounce his professorship and chooses intellectual and social isolation in Canada, rather than remain in Europe and watch the brutal spectacle of the Second World War. His self-imposed exile from Britain to Canada on the eve of war (engineered by him without Hester’s knowledge) is a form of “protest” against the ravening psychosis of history, of which the coming war figures as a prime example. Rather than become what he imagines as inevitable — an apologist for the collapse of imperialism — he gives up his teaching post, offers a condescending farewell to his mother and siblings, and thrusts himself and his wife into poverty.

The couple’s ultimately disastrous move to Momaco (the fictional double for Toronto) accelerates the process by which René’s sense of agency shrinks to that of a small room. In this respect, the novel is a fascinating example of the kind of externalized psychology Lewis believed in. That is to say, he wasn’t a believer in psychoanalysis or any interior notion of consciousness; mind and body are locked in combat with each other, but the field of battle is always an external one. Lewis tended to regard people (himself included) as having what one might call an exoskeletal psychology; relationships were about the external play and clash of shells, carapaces, pelts, rather than the internal conflicts of different souls or psyches. The novel is a compelling anatomization of Harding’s psychic collapse, whose overweening intellectual arrogance and seemingly limitless capacity for denial lead him and his wife into a domestic inferno.

Wyndham Lewis and his wife, Gladys, aboard the

Empress of Britain

,

bound for North America in September 1939.

This dualism, which recalls that of Descartes (Lewis gave Harding the name René with good reason), is projected both onto the Hardings’ marriage and onto the room they are forced to inhabit. These projections become the occasion for one of the most sustained metaphors in the novel. Part Two of the story, entitled “The Room,” is an extended meditation on the emotional effects of co-existing in a hotel room extending only twenty-five feet by twelve. The Hardings’ relationship becomes a study in paranoia as the Room begins to take on the status of a separate consciousness, as if a mind were something which “could be entered through a door and sat down in” (

Self Condemned

, 214). As their idea of themselves as independent people continues to crumble, bodies become estranged from their voices. The voice, an important symbol of one’s individuality, begins to attach itself to the Room, and not necessarily to René or Hester.

In another sense, their marriage, descending as it does into depression, suspicion, and mutual accusation, is a microcosm of the global conflict raging outside the walls of their cell. The Hardings’ confinement is, the novel suggests, a phenomenon that ranges over the whole continent “like the Chinese toy of box within box within box. And these boxes were all of a piece, all cut out of the same stuff. They were part of the same organism, this new North American organism. Their cells would have the same response to a given stimulus” (

Self Condemned

, 226). Hotel Blundell can be hived off from these containers as a “microcosm” of the world outside (

Self Condemned

, 227) — a “highly unstable box” that contains and is contained by psychosis. The hotel is a site of constant violence; they overhear brutal domestic abuse, a beloved worker in the hotel, Affie, is murdered, and René himself is slugged in a tavern. This cramped space at first permits René to give vent to an increasingly misogynistic attitude to his wife. He casts himself in the role of mind, and she in the role of body; his frankly ugly fantasies that her only worth is as a sexual object slowly recedes to yield a new insight — “In the other world, Hester, I treated you as you did not at all deserve. I cut a poor figure as I look back at myself ” (

Self Condemned

, 281).

On the surface, René’s acknowledgment of his former brutality seems admirable, even romantic, as he concedes that “This tête-à-tête of ours over three years has made us as one person.... It is only when years of misery have caused you to grow into another person in this way that you can really know them.... I am talking to myself and we are one” (

Self Condemned

, 281). But this rather banal declaration of love and vulnerability has a sinister undertone. The oneness he feels is simply another version of the egoism that drove them from England in the first place. As he begins the slow process of resuscitating his intellectual career, René’s smug sense of superiority revives along with it. In effect, their relationship is a tragic allegory of the global catastrophe from which they seek refuge. The disaster ends in marking the hotel itself; one blazingly cold winter night it goes up in flames, and in the aftermath of fighting the flames, the building is encased in a hollow shell of thick ice.

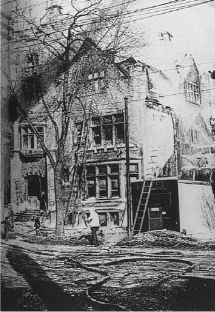

The Tudor Hotel, the

real-life Hotel Blundell, in

Toronto after the fire on

February 15, 1943.

Increasingly frustrated by her isolation, Hester argues with René about the possibility of returning to England. He flatly refuses, obsessing over the self-imposed notion that “it was Momaco or nothing, and he began to know this hysterically, fanatically, almost insanely. For he knew quite well that it was a fearful thing to know” (

Self Condemned

, 361). His career, he now believes, is absolutely tied to North America, and that any other choice — namely, Hester’s choice, London — would be death. Work, his latest muse, takes her place. And with traumatic consequences. René’s abandonment leads to Hester’s suicide: she throws herself under a truck, severing her head and legs from her body. In a brilliantly written, gruesome scene of identification, René encounters the gaze of death:

Topmost was the bloodstained head of Hester, lying on its side. The poor hair was full of mud, which flattened it upon the skull. Her Eye protruded: it was strange it should have the strength to go on peering in the darkness. René took a step forward towards the exhibit, but he fell headlong, striking his forehead upon the edge of the marble slab.... As he fell it had been his object to seize the head and carry it away with him. [

Self Condemned

, 425]

How does one confront a scene like this? Hester continues to peer without seeing into the darkness. She looks at him, but she neither sees nor recognizes him. Just as he wouldn’t see her point of view in life, René must face that her perspective is now utterly closed to him. But why does he reach for her severed head? Why this grotesque gesture? It is as if he is trying, even after her death, to bring her gaze into line with his, as if they could again have the single perspective he fought so long to wrest from her. The desecration of her body is a radical form of denial — not just of the fact of her death but that he is in part responsible. In a variant ending to the novel, Lewis brings the Hardings back to London, by turns condemning René to working as an academic hack, and Hester to her suicide. But the important difference between the two endings (and the published one is superior, in my opinion) is that it focuses on René’s emotional collapse and the hollowing out of his psyche. In the published version, the inability to look upon his guilt produces a total dissociation from reality, which the novel calls “The White Silence.”

He falls into another kind of cell — an achromatic prison that cuts off all feeling and all perception, a blinding labyrinth in which “the mind began to dream of white rivers which led nowhere, which developed laterally, until they ended in a limitless white expanse” (

Self Condemned

, 428). When he slowly emerges from this psychosis, he finds himself haunted by his dead wife. He comes to dismiss these apparitions as “Hesteria,” effectively placing the blame for her death and his illness exclusively on her. And this gesture produces the final irony — it is in this moment that he is truly condemning himself; his academic career revives and flourishes, but at the price of his humanity. He is now, like the hotel that once housed him, a glacial, fiery husk of a man awaiting death. The chilling clarity with which Lewis is able to write such an agonizing, yet human novel is a testimony to his enduring power as a prose stylist. And the fact that he doesn’t flinch from telling us this story is an avowal of his confidence and respect for us, his readers.

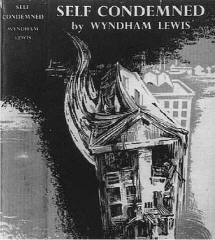

The original dust jacket, with

an illustration by Michael

Ayrton, of the first edition of

Self Condemned

, which was

first published in 1954.

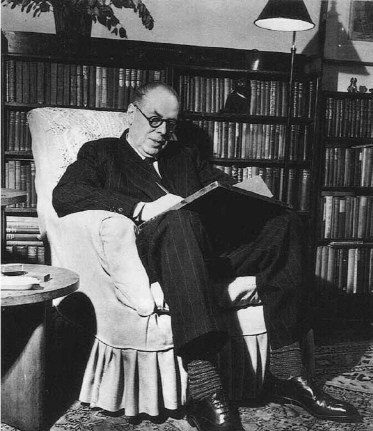

Wyndham Lewis continued to write even after becoming blind in 1951.Three

years later he published

Self Condemned

.

Some Books by Wyndham Lewis

America and Cosmic Man

. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1948.

America, I Presume

. New York: Howell, Soskin and Company, 1940.

The Apes of God

. Ed. Paul Edwards. Santa Barbara, CA: Black Sparrow Press, 1981.

The Art of Being Ruled

. Ed. Reed Way Dasenbrock. Santa Rosa, CA: Black Sparrow Press, 1989.

Blast

. 2 vols. Santa Barbara, CA: Black Sparrow Press, 1981.

Blasting and Bombardiering: An Autobiography (1914–1926)

. London: John Calder, 1982.

The Childermass

. London: Chatto and Windus, 1928.

The Complete Wild Body

. Ed. Bernard Lafourcade. Santa Barbara, CA: Black Sparrow Press, 1982.

The Hitler Cult, and How It Will End

. London: Dent, 1939.

The Jews — Are They Human?

London: George Allen and Unwin, 1939.

Malign Fiesta

. London: Methuen, 1955.

Monstre Gai

. London: Methuen, 1955.

Men Without Art

. Ed. Seamus Cooney. Santa Rosa, CA: Black Sparrow Press, 1987.

The Revenge for Love

. Ed. Reed Way Dasenbrock. Santa Rosa, CA: Black Sparrow Press, 1991.