Setting (23 page)

Authors: Jack M Bickham

Once the interview begins, strive to be cool and confident. You needn't apologize for being there. Remember that it's your interview, and you can quietly control the situation.

It may be intimidating to walk into an interview with a revered local historian, for example, or with a famous doctor. The impulse may be to start apologizing for being so uninformed in the expert's field. But what you have to remember is that your subject may be an expert in her field, but you are the expert in yours. I have often told a subject something like, "I don't know a lot about quasars, but I'm a professional in my field just as you are in yours. If we work together, we can make it possible for laymen to get a much better appreciation for all this."

This is not an egotistical attitude, but simply a realistic one. You will be far superior to most of your interviewees in communication skills. They respect that, if your attitude and demeanor demonstrate that you are.

A professional attitude and conduct during an interview, in other words, means that you will not be apologetic or sycophantic. You will be cool and friendly, as relaxed as you can be, properly respectful, and organized. You will ask your questions, get your information, say thank you kindly, and use no more of the subject's valuable time than necessary.

Should you ask to tape an interview? Yes. But some sources will say no, or be so nervous about the machine that they watch it instead of you, and never get into the interview. In such situations, the recorder has to be shut off and put back in your attache case. In any event, the recorder is no substitute for your notebook; it is at best a fall-back device used to clarify some point in your notes, or double-check the accuracy of a quote you've written down. You can't present a sound recording in your story; you have to transcribe information and recast it for story use. Notes taken at the time will show your instant reading of what's most important about the things being said. They will have none of the "hums" and "hahs" and background noise of the tape recording.

It is not necessary to know shorthand or speed writing to take good interview notes. You will be looking for information and can condense your notes. Often you will quickly jot down fragmentary facts, which are all you need for your setting.

Finally, when the interview is over —when you have the needed information or your allotted time is up—close the session promptly, express gratitude, and be on your way. It always helps to close with the suggestion that a later question might arise, and a request for permission to call or write back if such occurs.

Library sources

are not as dynamic as an interview, but often are extremely vital. Some of these are mentioned in various parts of the main text, but the most common ones should be mentioned here.

Whenever you visit the library, it goes without saying that you should be armed with notebooks and a couple of ballpoint pens or pencils. Many materials can't be checked out, and you will have to make notes in the library's reading area.

Much of the following will be old hat to you if you are a regular user of your local public library, but if you haven't visited the library very often, or are possibly intimidated by it, then it's probably time to get reacquainted.

Libraries of medium size or larger have long since been computerized. For a person unfamiliar with such systems, walking into the lobby and being confronted by video display terminals rather than the old, familiar card catalogs, can be off-putting. But cards and computers work similarly, usually being cross-indexed by subject matter, titles and authors' names. A few minutes' work with either system will set you at ease. And librarians usually are most eager to be of assistance.

Travel guides, atlases and local or regional histories can be found in even smaller libraries. These are always worth checking into. You may find specialized materials such as genealogical collections which sometimes contain rare old photographs. (Some libraries have collections of old photos that can give you priceless insights into an area's history.) Encyclopedias may provide good general information and old newspaper files may be most helpful. Larger libraries will contain extensive microfilm collections of many older archives and collections. The Draper collection, for example, is a massive collection of documents and written interviews pertaining to the early history of Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin and Indiana; filling hundreds of rolls of microfilm, its home is at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Wisconsin. But copies are available in numerous other libraries. Your librarian may be the easiest source for information about such materials.

Don't overlook the periodicals room in your library; it may contain local or regional magazines with just the information you want. There will also probably be a subject cross-index to more recent magazines if it's a larger library, and this might quickly send you to a magazine article that you did not know about.

When checking any library source, of course, carefully study the footnotes and bibliographies; these can often lead you to the titles of other source materials. And if some of these are not available locally, ask about getting them through an interli-brary loan.

If you check a book or periodical out of the library, remember that it is still incumbent upon you to make notes on information you may wish to use in constructing your story setting. Taking a book to the local copy shop and duplicating many pages is in violation of federal copyright law, and even if you find an unscrupulous copy shop that will do it for you, you should resist the temptation. Writers, of all people, should be keenly aware that unauthorized copying of printed material is not only illegal, but grossly unethical. Information from a publication can be used, but such use without giving credit to the source is unethical. Copying someone's exact literary style violates copyright.

If you are planning a major piece of fiction in a certain setting which requires that considerable research material be used over a considerable period of time, you may not want to be restricted by the library's limited borrowing time. Or you may learn that there is an edition of a book published later than the copy in the library's possession. In such cases you may turn to other sources of information.

Commercial sources

is just a fancy phrase meaning your local bookstores. These stores will have sections devoted to broad categories such as history, travel, sociology, etc. By visiting a few of them you will quickly learn which one has the best specialized sections.

You may find books at the store which are not in your library. I will be surprised if you don't, as all libraries seem to be strapped for funds and behind in their acquisitions. If you buy books, be sure to keep your receipt for possible tax-deduction purposes. If you're like me, you'll buy only books that you can see will have long-term research value to you, but that won't keep you from buying quite a few as you begin to build your research library.

Many colleges and universities have presses which specialize in certain areas of information. The University of Oklahoma Press, for example, has for years published many fine histories and biographies involving the western frontier, and not just Oklahoma-related items. Some of the best books currently in print about gold mining and outlawry in Montana have been published by Oklahoma. In like manner, the University of Nebraska Press has published many very fine books about Native

American history and lore. Most bookstores will either stock some of these specialized university press titles, or have access to their (as well as commercial publishers') catalogs. They'll also have a list of books currently in print, probably on microfiche, and can check specific titles and publishers for you.

Just browsing a good bookstore will sometimes reveal a magazine or a book you didn't know existed. Don't forget to browse the travel section, especially. Such books as the Fodors travel guides or the Michelin guides include detailed maps, brief histories and descriptions, and wonderful photos that can give a feel for a place.

Another commercial source, often overlooked, is your local travel agency. They're in the business of making reservations and selling tickets, so I wouldn't expect one of their busy (commission) agents to spend much time answering your questions, but most agencies have racks of tourist-luring brochures and maps free for the asking. Invariably such materials include an address where you can write for additional information.

Government sources

of information for story settings range from your local county or state agricultural agent to national and even international organizations. Your city hall or courthouse might be the place to start. Is there some kind of agricultural extension service available? You may not want to know much about farming, but maybe your story setting includes a backyard flower garden; extension service offices often have tremendous amounts of information available in pamphlet form for such activities as this, too. Almost surely there is a local Civil Defense office of some kind. There are dozens and dozens of CD brochures available on everything from drinking water to weather forecasting to nuclear radiation. There may be an extensive library of area legal documents somewhere, and these could provide setting information in the form of history that you could get no other way.

In larger cities you can call a United States Government number to order government pamphlets of all kinds. Some are free, none are expensive. There is even a document you can buy which lists all the other documents available. This is a valuable resource because a myriad of federal agencies are in the publishing business.

The United Nations is a gold mine of printed information on matters of industry, health and science around the world. The organization's materials can be mail-ordered out of New York. If you are looking for factual data to be used as part of the setting in a story set abroad, the UN may be your best source, and again the cost is reasonable.

Most government agencies of the kind we're talking about here have public information as a priority part of their agenda. (If you were head of a federal government agency dependent on taxpayer support for existence, you would want to tell the taxpayers all about your operations and expertise, wouldn't you?) A simple letter to an organization such as NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) or NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Adminstration, including what we once called the weather bureau) is likely to inundate you with information if you ask for it. The Department of Agriculture is another gold mine.

Computer research

is another possible avenue of setting information. A number of standard library-type sources such as encyclopedias are online with major computer database services such as CompuServe or Prodigy. If you are heavily into electronic communications via the computer, there are specialized databases of all kinds. You may also be interested in commercially available computer programs available on floppy disk (or on CD-ROM); these let you "dial up" deeply detailed information on various regions of the world, or even major cities. More of such material is coming onto the market all the time.

Correspondence

may go well beyond sending for brochures and pamphlets. If you locate the name of a company or individual that might have information useful for your setting work, it never hurts to write a letter asking specific questions or seeking an interview. I had a cordial response to such a routine letter of inquiry and enjoyed months of letters back and forth as I explored a topic in far greater detail than I ever imagined possible.

In a letter of this type, it's important to say who you are and how you're qualified (as a writer, not in their field!), generally and briefly what your project is, and to provide a sample specific question or two. Then sit back and see what returns. Sometimes it's a joyous surprise. (Once I got a thirty-pound box of materials from a scientist at NOAA, for example.)

Local experts

are another source of setting information not to be overlooked. It may be the old codger sitting on the park bench downtown who knows the town's history better than anyone. Or it might be a woman living nearby who has devoted half her life to learning all she can about a city and a lifestyle halfway around the planet. By all means ask your friends and associates if they know of anyone in the area you're researching. Ask at the library as well, as librarians often know such experts. Such a person will sometimes give you not only good factual information, but a sense of the feeling of a place or time, anecdotes, a loving look at something or someplace otherwise unavailable.

In all cases, whatever kind of research you do, keep good notes. Develop a standardized method of hanging onto them, be it file cards, file folders, computer disk, or whatever. Learn to honor research, and it will be your best companion now and for all your writing career.

APPENDIX 2

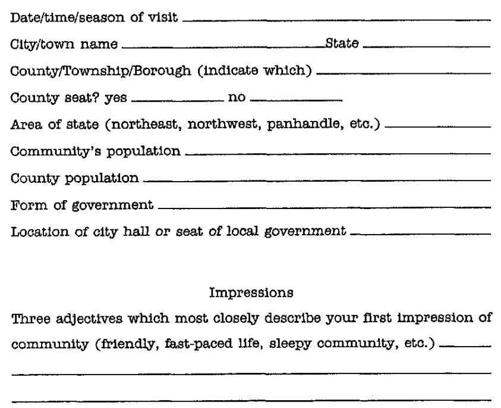

NANCY BERLAND'S SETTING RESEARCH FORM