Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality (10 page)

Read Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality Online

Authors: Christopher Ryan,Cacilda Jethá

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social Science; Science; Psychology & Psychiatry, #History

“Extended receptivity” is just a scientific way of saying that women can be sexually active throughout their menstrual cycle, whereas most mammals have sex only when it

“matters”—that is, when pregnancy can occur.

If we accept the assumption that women are not particularly interested in sex, other than as a way to manipulate men into sharing resources, why would human females have evolved this unusually abundant sexual capacity? Why not reserve sex for those few days in the cycle when pregnancy is most probable, as does practically every other mammal?

Two principal theories have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, and they couldn’t be more different. What anthropologist Helen Fisher has called “the classic explanation” goes like this: both concealed ovulation and extended (or, more accurately, constant) sexual receptivity evolved among early human females as a way of developing and cementing the pair bond by holding the attention of a constantly horny male mate. This capacity supposedly worked in two ways. First, because she was always available for sex, even when not ovulating, there was no reason for him to seek other females for sexual pleasure. Second, because her fertility was hidden, he would be motivated to stick around all the time to maximize his own probability of impregnating her and to ensure that no other males mated with her at any time—not just during a brief estrus phase. Fisher says, “Silent ovulation kept a special friend in constant close proximity, providing protection and food the female prized.”18 Known as

“mate guarding behavior” to scientists, contemporary women might call it “that insecure pest who never leaves me alone.” Anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy offers a different explanation for the unusual sexual capacity of the human female. She suggests that concealed ovulation and extended receptivity in early hominids may have evolved not to

reassure

males, but to

confuse

them. Having noted the tendency of newly enthroned alpha male baboons to kill all the babies of the previous patriarch, Hrdy hypothesized that this aspect of female sexuality may have developed as a way of confusing paternity among various males. The female would have sex with several males so that none of them could be certain of paternity, thus reducing the likelihood that the next alpha male would kill offspring who could be his.

So we’ve got Fisher’s “classic theory” proposing that women evolved their special sexiness as a way of keeping one man’s interest, and Hrdy saying it’s all about keeping several guys guessing. Fisher’s theory fits better with the standard model, in which females trade sex for food, protection, and so forth.

But this explanation works only if we believe that males—including our “primitive” ancestors—were interested in sex all the time with

just one female.

This contradicts the premise that males are hell-bent on spreading their seed far and wide, while simultaneously protecting their investment in their primary mate/family.

Hrdy’s “seeds of confusion” theory posits that concealed ovulation and constant receptivity would benefit a female who had multiple male partners—by preventing them from killing her offspring and inducing them to defend or otherwise aid her children. Hrdy’s vision of human sexual evolution puts females directly at odds with males, who would presumably view fertile females as “individually recognizable and potentially defensible resource packets” too valuable to share.

Either way, as depicted in the standard narrative, human sexual

prehistory

was

characterized

by

deceit,

disappointment, and despair. According to this view, both males and females are, by nature, liars, whores, and cheats. At our most basic levels, we’re told, heterosexual men and women have evolved to trick one another while selfishly pursuing

zero-sum,

mutually

antagonistic

genetic

agendas—even though this demands the betrayal of the people we claim to love most sincerely.

Original sin indeed.

* But who would argue the gourmand takes

less

pleasure in her food than the glutton?

* We examine the nature of sexual j’ealousy in more detail in Chapter 9.

CHAPTER FOUR

The Ape in the Mirror

Why should our nastiness be the baggage of an apish past

and our kindness uniquely human? Why should we not seek

continuity with other animals for our ‘noble’ traits as well?

STEPHEN JAY GOULD

‘Tis from the resemblance of the external actions of animals

to those we ourselves perform, that we judge their internal

likewise to resemble ours; and the same principle of

reasoning, carry’d one step farther, will make us conclude

that since our internal actions resemble each other, the

causes, from which they are deriv’d, must also be resembling.

When any hypothesis, therefore, is advanc’d to explain a

mental operation, which is common to men and beasts, we

must apply the same hypothesis to both.

DAVID HUME,

A Treatise of Human Nature

(1739–1740) Genetically, the chimps and bonobos at the zoo are far closer to you and the other paying customers than they are to the gorillas, orangutans, monkeys, or anything else in a cage. Our DNA differs from that of chimps and bonobos by roughly 1.6

percent, making us closer to them than a dog is to a fox, a white-handed gibbon to a white-cheeked crested gibbon, an Indian elephant to an African elephant or, for any bird-watchers who may be tuning in, a red-eyed vireo to a white-eyed vireo.

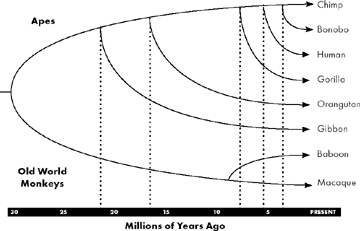

The ancestral line leading to chimps and bonobos splits off from that leading to humans just five to six million years ago (though interbreeding probably continued for a million or so years after the split), with the chimp and bonobo lines separating somewhere between 3 million and 860,000 years ago.1 Beyond these two close cousins, the familial distances to other primates grow much larger: the gorilla peeled away from the common line around nine million years ago, orangutans 16 million, and gibbons, the only monogamous ape, took an early exit about 22 million years ago. DNA evidence indicates that the last common ancestor for apes and monkeys lived about 30 million years ago. If you picture this relative genetic distance from humans geographically, with a mile representing about 100,000 years since we last shared a common ancestor, it might look something like this:

•

Homo sapiens sapiens:

New York, New York.

• Chimps and bonobos are practically neighbors, living within thirty miles of each other in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and York-town Heights, New York.

Both just fifty miles from New York, they are well within commuting distance of humanity.

• Gorillas are enjoying cheese-steaks in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

• Orangutans are in Baltimore, Maryland, doing whatever it is people do in Baltimore.

• Gibbons are busily legislating monogamy in Washington, D.C.

• Old-world monkeys (baboons, macaques) are down around Roanoke, Virginia.

Carl Linnaeus, the first to make the taxonomic distinction between humans and chimps (in the mid-18th century), came to wish he hadn’t. This division (Pan and

Homo)

is now regarded as being without scientific justification, and many biologists advocate reclassifying humans, chimps, and bonobos together to reflect our striking similarities.

Nicolaes Tulp, a well-known Dutch anatomist immortalized in Rembrandt’s painting

The Anatomy Lesson,

produced the earliest accurate description of a nonhuman ape’s anatomy in 1641. The body Tulp dissected so closely resembled a human’s that he commented that “it would be hard to find one egg more like another.” Although Tulp called his specimen an Indian Satyr, and noted that local people called it an orangutan, contemporary primatologists who have studied Tulp’s notes believe it was a bonobo.2

Like us, chimps and bonobos are African great apes. Like all apes, they have no tail. They spend a good part of their lives on the ground and are both highly intelligent, intensely social creatures. For bonobos, a turbocharged sexuality utterly divorced from reproduction is a central feature of social interaction and group cohesion. Anthropologist Marvin Harris argues that bonobos get a “reproductive payoff that compensates them for their wasteful approach to hitting the ovulatory target.”The payoff is “a more intense form of social cooperation between males and females” leading to “a more intensely cooperative social group, a more secure milieu for rearing infants, and hence a higher degree of reproductive success for sexier males and females.”3 The bonobo’s promiscuity, in other words, confers significant evolutionary benefits on the apes.

The only monogamous ape, the gibbon, lives in Southeast Asia in small family units consisting of a male/female couple and their young—isolated in a territory of thirty to fifty square kilometers. They never leave the trees, have little to no interaction with other gibbon groups, not much advanced intelligence to speak of, and infrequent, reproduction-only copulation.

Monogamy is not found in any social, group-living primate except—if the standard narrative is to be believed—us.

Anthropologist Donald Symons is as amazed as we are at frequent attempts to argue that monogamous gibbons could serve as viable models for human sexuality, writing, “Talk of why (or whether) humans pair bond like gibbons strikes me as belonging to the same realm of discourse as talk of why the sea is boiling hot and whether pigs have wings.”4

Primates and Human Nature

If Thomas Hobbes had been offered the opportunity to design an animal that embodied his darkest convictions about human nature, he might have come up with something like a chimpanzee. This ape appears to confirm every dire Hobbesian assumption about the inherent nastiness of pre-state existence. Chimps are reported to be power-mad, jealous, quick to violence, devious, and aggressive. Murder, organized warfare between groups, rape, and infanticide are prominent in accounts of their behavior.

Once these chilling observations were published in the 1960s, theorists quickly proposed the “killer ape” theory of human origins. Primatologists Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson summarize this demonic theory in stark terms, finding in chimpanzee behavior evidence of ancient human blood-lust, writing, “Chimpanzee-like violence preceded and paved the way for human war, making modern humans the dazed survivors of a continuous, 5-million-year habit of lethal aggression.”5

Before the chimp came to be regarded as the best living model of ancestral human behavior, a much more distant relative, the savanna baboon, held that position. These ground-dwelling primates are adapted to the sort of ecological niche our ancestors likely occupied once they descended from the trees. The baboon model was abandoned when it became clear that they lack some fundamental human characteristics: cooperative hunting, tool use, organized warfare, and power struggles involving complex coalition-building. Meanwhile, Jane Goodall and others were observing these qualities in chimpanzee behavior. Neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky—an expert on baboon behavior—notes that “chimps are what baboons would love to be like if they had a shred of self-discipline.”6

Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that so many scientists have assumed that chimpanzees are what humans would be like with just a bit

less

self-discipline. The importance of the chimpanzee in late twentieth-century models of human nature cannot be overstated. The maps we devise (or inherit from previous explorers) predetermine where we explore and what we’ll find there. The cunning brutality displayed by chimpanzees, combined with the shameful cruelty that characterizes so much of human history, appears to confirm Hobbesian notions of human nature if left unrestrained by some greater force.

Table 1: Social Organization Among Apes7

Egalitarian and peaceful,

bonobo communities are maintained primarily through social

bonding

between females,

although females bond with Bonobo

males as well. Male status derives from the mother. Bonds between son and mother are lifelong.

Multimale-multifemale mating.

The bonds between males are strongest and lead Chimpanzee to constantly shifting

male coalitions.

Females move through overlapping ranges within

territory patrolled by males, but don’t form strong bonds with other females or any

particular male.

Multimale-multifemale

mating.

By far the most diverse social species among the primates, there is plentiful evidence of

all types

Human

of socio-sexual bonding, cooperation, and

competition

among contemporary humans.

Multimale-multifemale mating.*

Generally, a single dominant male (the so-called

“Silverback”) occupies a range for his family unit composed of several females and young.

Gorilla

Adolescent males are forced out of the group as they reach sexual maturity. Strongest social bonds are between the male and adult

females.

Polygynous mating.