Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality (15 page)

Read Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality Online

Authors: Christopher Ryan,Cacilda Jethá

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social Science; Science; Psychology & Psychiatry, #History

ring, whatever). Small writes, “The only consistent interest seen among the general primate population is an interest in novelty and variety…. In fact,” she reports, “the search for the unfamiliar is documented as a female preference more often than is any other characteristic our human eyes can perceive.”16

Frans de Waal could have been referring to any of the previously mentioned Amazonian societies when he wrote that the male “has no idea which copulations may result in conception and which may not. Almost any [child] growing up in the group could be his…. If one had to design a social system in which fatherhood remained obscure, one could hardly do a better job than Mother Nature did with [this]

society.”17 Though de Waal’s words are applicable to any of the many societies who engage in ritualized extra-pair sex, he was, in fact, writing of the bonobo, thus underscoring the sexual continuity linking the three most closely related apes: chimps, bonobos, and their conflicted human cousins.

In light of the hypersexuality of humans, chimps, and bonobos, one wonders why so many insist that female sexual exclusivity has been an integral part of human evolutionary development for over a million years. In addition to all the direct evidence presented here, the circumstantial case against the narrative is overwhelming.

For starters, recall that the total number of monogamous primate species that live in large social groups is precisely

zero

—unless you insist on counting humans as the one and only example of such a beast. The few monogamous primates that do exist (out of hundreds of species) all live in the treetops. Primates aside, only 3 percent of mammals and one in ten thousand invertebrate species can be considered sexually monogamous. Adultery has been documented in

every

ostensibly monogamous human society ever studied, and is a leading cause of divorce all over the world today. But even in the latest editions of his classic book

The Naked Ape,

the same Desmond Morris who observed soccer players happily sharing their lovers still insists that “among humans sexual behavior occurs almost exclusively in a pair-bonded state,” and that “adultery reflects an imperfection in the pair-bonding mechanism.”18

That’s a major minor “imperfection.”

As we write these words, CNN reports that six adulterers are being stoned to death in Iran. Before the hypocritical sinners throw the first stones, the male adulterers will be buried up to their waists. In a sickening gesture toward chivalry, the women will be buried to their necks, presumably to bring a quicker death to these women who dared consider their bodies their own. Such brutal execution of sexual transgressors is anything but an oddity, historically speaking.

“Judaism, Christianity, Islam and Hinduism each share a fundamental concern over the punishment for a woman’s sexual freedom,” says Eric Michael Johnson. “Whereas any

‘man that committeth adultery with another man’s wife [both]

the adulterer and the adulteress shall be put to death,’

(Leviticus 20:10) but any unmarried woman who has sexual relations with an unmarried man shall be brought ‘to the door of her father’s house, and the men of her city shall stone her with stones that she die’ (Deuteronomy 22:21).”19

Yet even after centuries of such barbaric punishment, adultery persists everywhere, without exception. As Alfred Kinsey noted back in the 1950s, “Even in cultures which most rigorously attempt to control the female’s extramarital coitus, it is perfectly clear that such activity does occur, and in many instances it occurs with considerable regularity.”20

Think about that.

No

group-living nonhuman primate is monogamous, and adultery has been documented in

every

human culture studied—including those in which fornicators are routinely stoned to death. In light of all this bloody retribution, it’s hard to see how monogamy comes “naturally” to our species. Why would so many risk their reputations, families, careers—even presidential legacies—for something that runs

against

human nature? Were monogamy an ancient, evolved trait characteristic of our species, as the standard narrative insists, these ubiquitous transgressions would be infrequent and such horrible enforcement unnecessary.

No creature needs to be threatened with death to act in accord with its own nature.

The Promise of Promiscuity

Modern men and women are obsessed with the sexual; it is

the only realm of primordial adventure still left to most of us.

Like apes in a zoo, we spend our energies on the one field of

play remaining; human lives otherwise are pretty well caged

in by the walls, bars, chains, and locked gates of our

industrial culture.

EDWARD ABBEY

As we consider alternate views of prehistoric human sexuality, keep in mind that the core logic of the standard narrative pivots on two interlocking assumptions:

• A prehistoric mother and child needed the meat and protection a man would provide.

• A woman would have had to offer her own sexual autonomy in exchange, thus assuring him that it was his child he was supporting.

The standard narrative is founded upon the belief that the exchange of protein and protection for assured paternity was the best way to increase the odds of a child’s survival to reproductive age. Survival of offspring is, after all, the primary engine of natural selection as described by Darwin and subsequent theorists. But what if risk to offspring were mitigated more effectively by behavior that encouraged the

opposite

arrangement? What if, rather than one man agreeing to share his meat, protection, and status with a particular woman and her child, sharing were generalized? What if group-wide sharing offered a more effective approach to the risks our ancestors encountered in the prehistoric world? And in light of these risks, what if paternity

uncertainty

were more beneficial to the child’s chances of survival, as more men would take an interest in him or her?

Again, we’re not suggesting a

nobler

social system, just one that might have been better suited to meeting the challenges of prehistoric conditions and more effective in helping people survive long enough to reproduce.

This sharing-based social life is far from uniquely human. For example, vampire bats in Central America feed on the blood of large mammals. But not every bat finds a meal each night.

When they return to their dens, those bats who have had a good night regurgitate blood into the mouths of bats who have not had as much luck. Recipients of such largess are likely to return the favor when the conditions have reversed themselves, but are less likely to give blood to bats who have denied them in the past. As one reviewer put it, “The key to this bit for bat process is the individual bat’s ability to remember the history of its relationships with all other bats living in its den. This mnemonic requirement has driven the evolution of vampire bat brains, which possess the largest neocortex of all known bat species.”21

We hope the thought of vampire bats coughing up (coughing down?) blood for their non-blood relatives is graphic enough to convince you that sharing isn’t innately “noble.” Some species, in some conditions, have simply found that generosity is the best way to reduce risk in an uncertain ecological context.

Homo sapiens

appears to have been such a species until relatively recent times.22

The near universality of fierce egalitarianism among foragers suggests there was really little choice for our prehistoric ancestors. Archaeologist Peter Bogucki writes, “For Ice Age mobile hunting societies, the band model of social organization, with its obligatory sharing of resources, was really the only way to live.”23 It makes perfect Darwinian sense to suppose that prehistoric humans would choose the path that offered the best chance of survival—even if that path required egalitarian sharing of resources rather than the self-interested hoarding of resources many contemporary Western societies insist is basic human nature. After all, Darwin himself believed a tribe of cooperative people would vanquish one composed of selfish individualists.

Are we preaching far-fetched flower-power silliness? Hardly.

Egalitarianism is found in nearly all simple hunter-gatherer societies that have been studied anywhere in the world—groups facing conditions most similar to those our ancestors confronted 50,000 or 100,000 years ago. They’ve followed an egalitarian path not because they are particularly noble, but

because it offers them the best chance of survival.

Indeed, under these conditions, egalitarianism may be the

only

way to live, as Bogucki concluded. Institutionalized sharing of resources and sexuality spreads and minimizes risk, assures food won’t be wasted in a world without refrigeration, eliminates the effects of male infertility, promotes the genetic health of individuals, and assures a more secure social environment for children and adults alike. Far from utopian romanticism, foragers insist on egalitarianism because it works on the most practical levels.

Bonobo Beginnings

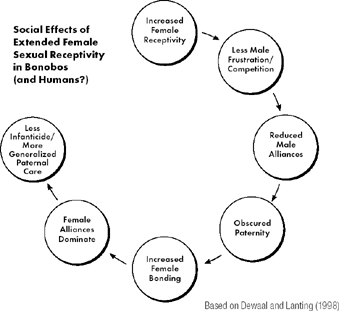

The effectiveness of sexual egalitarianism is confirmed by female bonobos, who share many otherwise unique traits with humans and no other species. These sexual characteristics have direct, predictable social consequences. De Waal’s research has demonstrated, for example, that the increased sexual receptivity of the female bonobo dramatically reduces male conflict, when compared with other primates whose females are significantly less sexually available. The abundance of sexual opportunity makes it less worthwhile for males to risk injury by fighting over any particular sexual opportunity. Since alliances among male chimps, for example, generally serve to keep competitors away from an ovulating female, or to attain the high status that brings more mating opportunities to a given male, the principal motivation for these unruly gangs evaporates in the relaxing heat of bonobos’ plentiful sexual opportunity.

These same dynamics apply to human groups. Aside from

“the social habits of man as he now exists,” why presume the monogamous pair-based model of human evolution currently favored would have been adaptive for early humans, but not for bonobos in the jungles of central Africa? Unconstrained by cultural restrictions, the so-called

continual responsiveness

of the human female would fulfill the same function: provide plentiful sexual opportunity for males, thereby reducing conflict and allowing larger group sizes, more extensive cooperation, and greater security for all. As anthropologist Chris Knight puts it, “Whereas the basic primate pattern is to deliver a periodic ‘yes’ signal against a background of continuous sexual ‘no’, humans [and bonobos] emit a

periodic ‘no’ signal against a background of continuous

‘yes’.”24Here we have the

same behavioral and physiological

adaptation,

unique to two very closely related primates, yet many theorists insist the adaptation must have completely different origins and functions in each.

Based on Dewaal and Lanting (1998)

This increased social cohesion is, in fact, probably the most common explanation for the potent combination of extended receptivity and hidden ovulation found

only

in humans and bonobos.25 But most scientists seem to see only half of this logical connection, as in this abstract: “Females who concealed ovulation were favored because the group in which they lived maintained a peaceful stability that facilitated monogamy, sharing and cooperation.”26 It’s clear how greater female sexual availability could increase sharing, cooperation, and peaceful stability, but why monogamy should be added to the list is a question that not only goes unanswered but is almost never asked.

Those anthropologists willing to acknowledge the realities of human sexuality see its social benefits clearly. Beckerman and Valentine point to the fact that partible paternity defuses potential conflicts between men, noting that such antagonisms tend to be unhelpful to a woman’s long-term reproductive interests.

Anthropologist

Thomas

Gregor

reported

eighty-eight ongoing affairs among the thirty-seven adults in the Mehinaku village he studied in Brazil. In his opinion, extramarital relationships “contribute to village cohesion,” by