Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality (23 page)

Read Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality Online

Authors: Christopher Ryan,Cacilda Jethá

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social Science; Science; Psychology & Psychiatry, #History

“bellum omnium contra omnes”

(the war of all against all).

But the false view of prehistoric human life summed up in Hobbes’s pithy dictum “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” is still almost universally accepted.

Having established that prehistoric human life was highly social and decidedly

not

solitary, we now briefly address the other elements in Hobbes’s description in the following four chapters, before continuing with a more direct discussion of overtly sexual material. We hope readers primarily interested in sex will bear with us because what might at first seem a detour is in fact a shortcut to a clearer vision of the day-to-day lives of our ancestors, a vision that will help you make better sense of the material that follows, as well as of your own world.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

“The Wealth of Nature”

(Poor?)

The point is, ladies and gentleman, that greed, for lack of a

better word, is good. Greed is right, greed works. Greed

clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the

evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms … has marked

the upward surge of mankind.

“GORDON GEKKO,” in the film

Wall Street

What constitutes misuse of the universe? This question can be

answered in one word: greed…. Greed constitutes the most

grievous wrong.

LAURENTI MAGESA,

African Religion: The Moral Traditions of Abundant Life

Economics, “the dismal science,” was dismal right from the start.

On a late autumn afternoon in 1838, what may have been the brightest bolt of illumination ever to flash out of an overcast English sky struck Charles Darwin right upside the head, leaving him stunned by what Richard Dawkins has called “the most powerful idea that has ever occurred to a man.” At the very moment the great insight underlying natural selection came to him, Darwin was reading

An Essay on the Principle

of Population

by Thomas Malthus.1

If the measure of an idea is its endurance through time, Thomas Malthus deserves his spot as Wikipedia’s eightieth Most Influential Person in History. More than two centuries later, one would be hard pressed to find a single student of economics unfamiliar with the simple argument put forth by the world’s first professor of economics. You’ll recall that Malthus argued that each generation doubles geometrically (2, 4, 8, 16, 32 …), but farmers can only increase food supply arithmetically, as new fields are cleared and productive capacity is added in a linear fashion (2, 3, 4, 5, 6 …). From this crystalline reasoning follows Malthus’s brutal conclusion: chronic

overpopulation,

desperation,

and

widespread

starvation are intrinsic to human existence. Not a thing to be done about it. Helping the poor is like feeding London’s pigeons; they’ll just reproduce back to the brink of starvation anyway, so what’s the point? “The poverty and misery which prevail among the lower classes of society,” Malthus asserts,

“are absolutely irremediable.”

Malthus based his estimates of human reproductive rates on the recorded increase of (European) population in North America in the previous 150 years (1650–1800). He concluded that the colonial population had doubled every twenty-five years or so, which he took to be a reasonable estimate of the rates of human population growth in general.

In his autobiography, Darwin recalled that when he applied these dire Malthusian computations to the natural world, “it at once struck me that under these circumstances favorable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavorable ones

to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species. Here then I had at last got a theory by which to work …”2 Science writer Matt Ridley believes Malthus taught Darwin the “bleak lesson” that “overbreeding must end in pestilence, famine or violence,” convincing him that the secret of natural selection was embedded in the struggle for existence.

Thus was Darwin’s brilliance sparked by the darkest Malthusian gloom.3 Alfred Russel Wallace, who came up with

the

mechanism

underlying

natural

selection

independently of Darwin, experienced his own flash of insight while reading

the same essay

between bouts of fever in a hut on the banks of a malarial Malaysian river. Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw smelled the Malthusian morbidity underlying natural selection, lamenting, “When its whole significance dawns on you, your heart sinks into a heap of sand within you.” Shaw lamented natural selection’s

“hideous fatalism,” and complained of its “damnable reduction of beauty and intelligence, of strength and purpose, of honor and aspiration.”4

But while Darwin and Wallace made excellent use of the Malthus’s dire calculations, there’s a problem with them.

They don’t add up.

The tribes of hunters, like beasts of prey, whom they resemble

in their mode of subsistence, will… be thinly scattered over

the surface of the earth. Like beasts of prey, they must either

drive away or fly from every rival, and be engaged in

perpetual contests with each other…. The neighboring

nations live in a perpetual state of hostility with each other.

The very act of increasing in one tribe must be an act of

aggression against its neighbors, as a larger range of

territory will be necessary to support its increased

numbers…. The life of the victor depends on the death of the

enemy.

THOMAS MALTHUS,

An Essay on the Principle of

Population

If his estimates of population growth were even

close

to correct, Malthus (and thus, Darwin) would have been right to assume that human societies had long been “necessarily confined in room,” resulting in “a perpetual state of hostility” with one another. In

Descent of Man,

Darwin revisits Malthus’s calculations, writing, “Civilised populations have been known under favourable conditions, as in the United States, to double their numbers in twenty-five years … [At this] rate, the present population of the United States (thirty millions), would in 657 years cover the whole terraqueous globe so thickly, that four men would have to stand on each square yard of surface.”5

If Malthus had been correct about prehistoric human population

doubling

every

twenty-five

years,

these

assumptions would indeed have been reasonable. But he wasn’t, and they weren’t. We now know that until the advent of agriculture, our ancestors’ overall population doubled not every twenty-five years, but every

250,000 years.

Malthus (and thus, Darwin after him) was off by a factor of 10,000.6

Malthus assumed the suffering he saw around him reflected the eternal, inescapable condition of human and animal life.

He didn’t understand that the teeming, desperate streets of London circa 1800 were far from a reflection of prehistoric conditions. A century and a half earlier, Thomas Hobbes had made the same mistake, extrapolating from his own personal experience to conjure a mistaken vision of prehistoric human life.

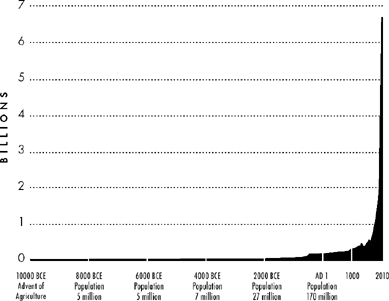

Estimated Global Population7

Thomas Hobbes was born to terror. His mother had gone into premature labor upon hearing that the Spanish Armada was about to attack England. “My mother,” Hobbes wrote many years later, “gave birth to twins: myself and fear.”

Leviathan,

the book in which he famously asserts that prehistoric life was

“solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” was composed in Paris, where he was hiding from enemies he’d made by supporting the Crown in the English Civil War. The book was nearly abandoned when he was taken with a near-fatal illness that left him at death’s door for six months. Upon publication of

Leviathan

in France, Hobbes’s life was now being threatened by his fellow exiles, who were offended by the anti-Catholicism expressed in the book. He fled back across the channel to England, begging the mercy of those he’d escaped eleven years earlier. Though he was permitted to stay, publication of his book was prohibited. The Church banned it. Oxford University banned it

and

burned it. Writing of Hobbes’s world, cultural historian Mark Lilla describes

“Christians addled by apocalyptic dreams [who] hunted and killed Christians with a maniacal fury they had once reserved for Muslims, Jews and heretics. It was madness.”8

Hobbes took the madness of his age, considered it “normal,” and projected it back into prehistoric epochs of which he knew next to nothing. What Hobbes called “human nature” was a projection of seventeenth-century Europe, where life for most was rough, to put it mildly. Though it has persisted for centuries, Hobbes’s dark fantasy of prehistoric human life is as valid as grand conclusions about Siberian wolves based on observations of stray dogs in Tijuana.

To be fair, Malthus, Hobbes, and Darwin were constrained by the lack of actual data. To his enormous credit, Darwin recognized this and tried hard to address it—spending his entire adult life collecting specimens, taking copious notes, and corresponding with anyone who could provide him with useful information. But it wasn’t enough. The necessary facts wouldn’t be revealed for many decades.

But now we have them. Scientists have learned to read ancient bones and teeth, to carbon-date the ash of Pleistocene fires, to trace the drift of the mitochondrial DNA of our ancestors.

And

the

information

they’ve

uncovered

resoundingly refutes the vision of prehistory Hobbes and Malthus conjured and Darwin swallowed whole.

Poor, Pitiful Me

We are enriched not by what we possess, but by what we can

do without.

IMMANUEL KANT

If George Orwell was correct that “those who control the past control the future,” what of those who control the distant past?

Prior to the population increases associated with agriculture, most of the world was a vast, empty place in terms of human population. But the desperate overcrowding imagined by Hobbes, Malthus, and Darwin is still deeply embedded in evolutionary theory and repeated like a mantra, facts be damned. For example, in his recent essay entitled “Why War?,” philosopher David Livingstone Smith projects the Malthusian