Shark Trouble (8 page)

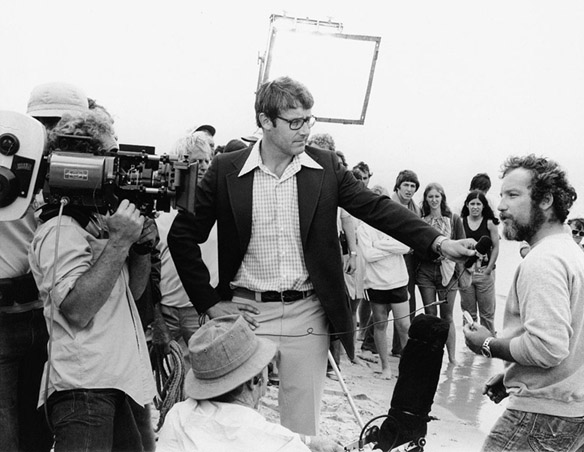

On the beach set of

Jaws

in the cold spring of 1974. Left to right, my wife, Wendy; PB; Roy Scheider (Chief Brody in the movie); and, in front of me, our five-year-old son, Clayton.

© UNIVERSAL PICTURES

Steven Spielberg preparing me for my scene as the television reporter on the beach on the Fourth of July.

© UNIVERSAL PICTURES

The intrepid reporter interviewing Richard Dreyfuss (Hooper) during the Fourth of July beach scene in

Jaws

.

© UNIVERSAL PICTURES

On the set of

The Deep

in Bermuda, 1976. Nick Nolte (

left

) had starred in the TV miniseries

Rich Man, Poor Man,

but this was his first leading role in a major feature film. The leather-covered cigarette lighters hanging around our necks, each stamped with the name of the movie, were gifts to cast and crew from the gutsy, game, and gorgeous Jacqueline Bisset (

right

).

© COLUMBIA TRISTAR

Two of the most memorable shows (for me) from ABC's

The American Sportsman

. As yet unaware that I'm leaking blood from a wound in my ankle, I've become an object of desire for an oceanic whitetip. My celebrated broomstick is about to meet its end.

© ABC SPORTS

Riding a giant manta ray in the Sea of Cortez. A second after he took this picture, Stan Waterman had his face mask knocked off and his nose bloodied by one of the manta's wings.

© STAN WATERMAN

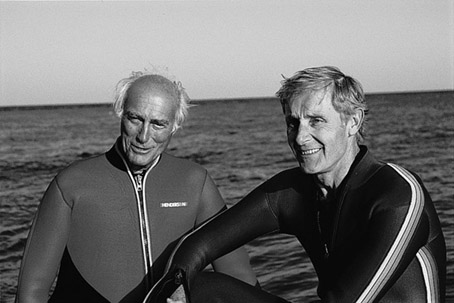

Stan Waterman,

left,

one of America's pioneer divers and underwater filmmakers, a gentle man of consummate charm and grace.

© HOWARD HALL/HOWARDHALL.COM

Stan greetingâwhile attempting to filmâa whale shark, the biggest fish in the sea.

© MARJORIE BANK

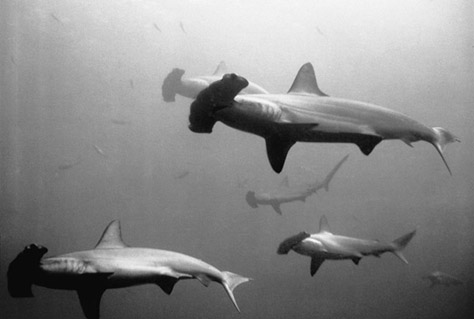

An armada of scalloped hammerheads in the Sea of Cortez. No one knows for certain why they gather in such numbersâperhaps it's a ritual related to breedingâbut they seem to have no interest whatsoever in human beings.

© HOWARD HALL/HOWARDHALL.COM

A silvertip in the South Pacific, one of the “sharkiest-looking” of all shark species.

© JENNIFER HAYES

One of several species of bull sharkâunpredictable and dangerous.

© HOWARD HALL/HOWARDHALL.COM

Prey's-eye view of a great white ambushing from behind and below. Many professional shark wranglers believe that if you're under water and a great white shows an aggressive interest in you, the smartest thing to do is ascertain that the shark

knows

you've seen it. Great whites depend so much on the element of surprise for a successful attack, says this theory, that if they know you've seen them, more often than not they'll abandon the attack on you and go instead in search of easier prey.

© JENNIFER HAYES

10

What to Do When Good Dives Go Bad

Â

Usually, when you're divingâbe it for sight-seeing, sport, or businessâyou don't want to see sharks, any more than you want to meet up with a bear while you're walking in the woods or with a pack of wolves while you're cross-country skiing.

Apex predatorsâthe creatures at the top of the food chain that, generally, have no natural enemies except others of their own species (and, of course, man)âhave a way of spoiling your whole day, even if they don't chase you down and tear you to bits in an aberrant fit of madness or hunger.

If you've had good training and/or a lot of experience as a diver, you know how to cope with equipment failures, symptoms of the several afflictions that can befall you under water, and other routine emergencies. (“Routine emergencies” is not an oxymoron, by the way, not when referring to the underwater world. Running out of air is a routine emergency: there are ways to deal with the problem, and often it is preceded by warning signs. Nonroutine emergencies strike from nowhere, are impossible to prepare for, and can cascade with unbelievable speed into disaster.)

No matter how experienced or well trained you are, however, you can never be completely prepared for the sudden appearance of one or more aggressive sharks. The reason? Here it comes again:

no matter how much we think we know, the truth is, none of us knows for certain what any shark will or won't do in a given situation.

Always remember that the shark is on its home range, and you are the intruder. Think of yourself as a trespasser in a yard posted with signs warning

BEWARE OF SHARKS

.

And if you see a shark, or sharks, try to keep it in view while you decide what to do next.

There are some cardinal rules for divers, but none of them is a guarantee. Here are some that, to me, make the most practical sense:

Rule #1: If you're diving on a reef and you see a shark, any shark, and it begins to behave erraticallyâshaking its head, hunching its back, lowering its pectoral finsâyou're probably being shown a territorial threat display, a warning to

scram

. Take it seriously. Slowly and calmly retreat. Get out of the water if possible, but at least get away from the area and to a part of the reef where you can find shelter on one or two sides. In my experience, all but the largest sharks will avoid a direct, head-on, frontal assault on a scuba diver.

Rule #2: If you're diving with a group, stay together and tighten up your formation. As a group you demonstrate size, strength, and confidence (never mind that it's a fraud; the shark doesn't know that). Don't stray alone out into open water, where you broadcast vulnerability.

Rule #3: If you're a photographer, you're carrying a camera, perhaps one housed in a hard, rugged case, which can be an effective defensive weapon. Usually, a shark that bites down on a camera housing will conclude that the entire entity associated with itâthat is, youâis unpalatable.

Rule #4: If you're not a photographer, make it a habit to dive with something in your hand that can be used to fend off a nosy predator: a sawed-off ski pole, maybe, an actual shark billyclub, or something like my broomstick. Nine times out of ten, a shark that comes too close or becomes too curious for comfort can be discouraged by a tap or two on the head or body. If that doesn't do the job, a vigorous jab often will.

Rule #5: Don't dive with dolphins. They can be an irresistible temptation. Dolphins look, sound, and act friendly, and they usually are. But oftentimes they also compete with sharks for the same prey, and to an excited shark a human being can appear to be a weak or wounded dolphin.

Rule #6: Some supposed experts insist that a diver should immediately exit the water at the first sight of any large shark, particularly a tiger, hammerhead, bull, mako, or great white. To me, the generalization is too general. Every encounter between diver and shark develops a situational dynamic of its own. (I do agree, however, that a diver who can't identify the particular species of shark that has appearedâand several species closely resemble othersâshould err on the side of caution and head for safety.)

The tiger sharks I dove with in Australia were interested in nothing but the bait laid out for them. Luckily for me, they dismissed humansâ

these

humans, at leastâas of no interest.

In the Sea of Cortez I dove with vast schools of scalloped hammerheadsâso many that, seen from beneath, they blocked out the sunâand not once did a single one of them express anything more than idle curiosity about us.

In deep water off Rangiroa, an atoll in the Tuamotu chain of islands in French Polynesia, photographer David Doubilet and I pursuedâto dicey depths between 150 and 200 feetâfive enormous great hammerheads. Great hammerheads are a species unto themselves, manifestly different from the schooling scalloped hammerheads, and these five were hefty, robust females, all fifteen feet or longer. Any one of them could have consumed either of us in two bites, but not one would pause long enough for David to take a photograph.

Rangiroa is also home to a small but healthy population of silky sharks, a particularly “sharky”-looking type of shark with a supersleek body and a perfect shark profile. Silkies are considered dangerous to man, but I've dived with the ones around Rangiroa half a dozen times or more, and I've never had trouble with any of them. Once, through a misunderstanding of signals between David and meâI thought he was signaling me to get closer to the shark, while what he was, in fact, signaling was that he was ill and about to vomit into his regulatorâI let a large silky come so close to my head that I could count the pores on its snout and see the texture of its yellowish eyeball. When at last I realized what was happening, I shrugged one of my shoulders, nudging the silky in the jaw, and it sped away.

Nor have I had trouble with any of the various kinds of bull sharks, though I know that many peopleâdivers as well as swimmersâhave. If I see a bull shark under water, I never take my eyes off it. In early September 2001, I noticed that some respected journalists and scientists were declaring that bull sharks actually

do

target human beings as food. I think the conclusion is rash and no more provable than other sweeping generalizations about any species of shark. On the other hand, I am convinced that bull sharks

are

dangerous to human beings, and they merit a greater measure of fear than most other species.

I'm just as wary of makos, though they're so fast that keeping them in sight is nearly impossible. Not only are makos the fastest sharks in the sea, and armed with a mouth full of scraggly knives, but they have a reputation for crankiness.

I've been in the water with a mako only once. It appeared as if by magic, and paused in front of cinematographer Stan Waterman, no more than two feet away. Before Stan could focus his camera, his safety diverâwhose sole job is to protect the back of the cameramanâpanicked and whacked the mako with his “bang stick,” a steel tube fitted on one end with a twelve-gauge shotgun-shell blank and a detonating mechanism. The explosion of the gases inside the cartridge blew a hole the size of a silver dollar in the mako's head, killing it instantly, and we watched the beautiful metallic blue body swirl away into the darkness of the deep.

Stan was furious; he had discerned no danger; he had had the mako in sight at all times, and it hadn't threatened him once. The gorgeous animal had died for nothing. Stan's safety diver was abashed and apologetic.

And then, finally, there is the shark for which no amount of instruction, training, warning, or anticipation can prepare a diver: the great white. Yes, there are a few helpful things to know, such as that you can reduce the creature's advantage by letting it know that

you

know that it sees you. Great whites are ambushers by trade, preferring to attack prey from below and behind. Theoretically, if you face down a great white, you may convince it that you're too much trouble to bother with. Theoretically.

I know an individual in South Africa who snorkels and scuba dives with great whites in the open (that is, with no cage), and he sometimes carries for protection a weighted piece of wood painted to resemble an enormous great white's head in “full gape”âmouth yawning open, upper jaw down and out in bite position. He claims that his bluff has several times deceived great whites and discouraged them from attacking him.

Still, nothing in the world can prepare the average scuba diverâor, for that matter, the average

shark

diverâfor an unplanned encounter with whitey. I know it to be true, for it happened to me several years ago.

The great Bermudian polymath Teddy Tucker was asked to journey to Walker's Cay in the Bahamas, to assess a pile of ancient cannons that had been discovered on the sandy bottom. The finder of the cannons wanted Teddy's opinion as to whether the guns were signs of a shipwreck in the immediate vicinityâin which case, if the wreck appeared to be from a significant era, he might finance an archeological expedition to preserve its remainsâor were merely a “dump,” cannons tossed overboard centuries ago from a storm-wracked ship trying to lighten itself enough to pass over the many reefs and shoals among which it had found itself trapped. Teddy would scour the rocks and coral nearby for alluvial stones that might have been used as ballast, and he would search for bits of wood or metal and for coralline overgrowth that could signal iron, bronze, silver, or sections of a ship's skeleton concealed beneath.

I accompanied Teddy as dogsbody, bat man, porter, and companion, not because he needed me but because I knew that a trip with Teddy was an adventure guaranteed, always fascinating, often exciting, and occasionally perilous. I had already written two novels based on or inspired by escapades with Teddy,

The Deep

and

The Island,

and more were to follow.

It took him only a few dives over a couple of days to conclude that the cannons were a dump. No ship had sunk with themâno ship big enough to carry this many guns, anyway, and none right here. Perhaps the ship had lightened up enough to clear the reefs and sail on to the safety of the open sea. Perhaps it had made a few hundred yards of headway and then come to grief on another reef. Perhaps the storm had broken the ship apart, sending different sections to float away to different destinations. Perhaps the ship had made it all the way home to England or Spain or France or Holland. The cannons were of English manufacture, but in an age when everyone pillaged and used everyone else's cannons and currencies (Spanish pieces of eight were legal tender in the United States, for example, until the middle of the nineteenth century), place of origin was proof of nothing further.

Unless and until the finder decided to spend the time and lavish sums of money to search naval archives and mount a proper underwater expedition, no one would ever know for certain the fate of the hapless ship.

One day, while Teddy was examining a stretch of reef, I returned to the cannons, intending to fan away the sand at the base of the heap of encrusted iron, in hopes of finding some small telltale sign of a wreck: an emerald ring, perhaps, or a gold chain. Something modest.

The water was clear and the visibility seemingly endless, so the cannons were in plain sight from the surface forty or fifty feet away. I remember the pile as being higher than I was tall and at least twenty-five or thirty feet long. A friend of ours was snorkeling on the surface, and he waved to me as I sank to the bottom and began to creep along the sand, fanning with my hand here and there to expose a crack or crevice that might be hiding what had, by now, become in my mind the Gem of Gems.

After a few pleasant but fruitless minutes of ambling and fanning, I heard a smacking sound from above. I looked up and saw that my snorkeling friend was slapping the surface and pointing down at meâor so it appeared. I looked at him for a moment, long enough to assure myself that he wasn't in trouble, then I waved to acknowledge him and continued on my way.

The slapping stopped, and now I heard the sound of swim fins churning through the water. I looked up and saw the snorkeler swimmingâno,

racing

âtoward the boat. He'd become bored, I assumed, or cold (though the water was soup warm). I kept going.

Not till much later did I learn that what he had been doing with all his noisy slapping was trying to save my life.

From his prospect high above, he had a clear and comprehensive view of the entire area: not just the cannons, but the sand plains that spread out from them on all sides. Seconds after I had begun to creep along the sand, he had seen, emerging from the gloom on the opposite side of the cannons, a great white shark. Not a big oneâten or twelve feet at most, probably a young maleâbut a great white shark nonetheless.

Anyone who has ever seen a great white in the water will never mistake it for any other species of shark. Seen from above, the great white has a unique profile. Its hefty, jumbo-jet fuselage is distinguished by what's called its caudal keel, a curved horizontal fin that protrudes just forward of the tail on both sides of its body. It resembles a diving plane on a submarine or a stabilizer on a ship, and it gives support to the tail, and streamlines the shark. Caudal keels exist in billfish and a few other species of sharks, but in none are they so pronounced. Seen from the side, a great white is thicker and more robust than, say, a silky; its snout is perfectly proportioned, not as sharp as a mako's, not as blunt as a tiger shark's. Seen head-on, it is broad-shouldered, neckless, its lower jaw slightly ajar and showing grabbing and tearing teeth, its upper lip looking sort of puckery, as if the upper jaw were toothless rather than home to row upon row of big, serrated triangular cutting teeth that lie relaxed, nearly horizontal, against the upper gums.

Seen from anywhere, it is a

big

shark, long and bulkyâa seventeen-foot female can weigh more than two tonsâand it moves with the ease and confidence of the toughest dude on the block.