Shark Trouble (7 page)

Drownproofing: A Survival Technique

Everyone who would swim in the sea should be compelled to learn an excellent survival technique called “drownproofing,” invented in the 1940s by a swimming coach named Fred Lanoue. Endorsed by the U.S. Public Health Service and taught at many schools, it's easy to learn and, as much as anything can be, idiotproof. (It is not, however, panicproof. Nothing is.)

The two premises of drownproofing are: (1) most people will float if their lungs are filled with air; and (2) it's much easier and less tiring to float vertically than horizontally. Most people's bodies

want

to float vertically, buoyed by the two big air sacs (the lungs) that stay near the surface, and with the heavy (bony and muscular) hips and legs dangling beneath.

Here's how to drownproof yourself:

Floating vertically, with your hands limp at your sides, take a deep breath, hold it, and let yourself hang there, with your face in the water and (optional but more relaxing) your eyes closed.

As soon as you feel that you'd like to take a breathâlong before that awful feeling when you know you

must

âexhale slowly through your nose. Raise your arms, and cross them in front of your face. Spread them as if you were parting curtains, and when your arms are extended, push your palms down toward your sides and tilt your head back. Your mouth will come out of the water. Take a breath, lower your head and arms, and let yourself bob in the water.

Every movement should be easy, deliberate, unhurried. You're not trying to go anywhere; there's no rush and no worry. When you hear your pulseâand you will, for the rhythms of your body become the focus of your mindâit should sound normal, not rapid. Fear and excitement waste energy and oxygen.

I can hear you muttering, “Easy for

you

to say.” But that's why you're practicing, so that if and when the time comes for you to save yourself, you'll be ready.

It won't take you long to feel at ease with the technique of drownproofing. When you do, leisurely lift your head out of the water, flutter-kick gently until your body is horizontal, and thenâon your back, with your hands paddling easily at your sidesâkick as often as is comfortable in the general direction of the shore.

If you tire, stop kicking, let your legs hang down again, and resume the drownproofing breathing until you feel you're ready to carry on. Remind yourself that you're not trying to “beat” the sea, nor is it trying to beat you.

We humans sometimes have an unfortunate tendency to anthropomorphize not only animals but the sea itself. We use words like

treacherous, savage,

and

killer

to describe natural phenomena like waves, currents, and storms. It is, I think, a symptom of our refusal to admit that we must coexist with nature, not compete with it or attempt to dominate it.

We

are

nature, and nature is us. We are of the sea and from the sea, and if we choose to venture into the sea, we must respect and appreciate it for what it is: an environment that is different but not hostile, accommodating to the educated and prepared, and fatal mostly to the foolhardy.

9

How to Avoid Shark Attack

Â

You've heard and read it a thousand times: the chances of your being killed by a shark are so tiny as to not be worth worrying about.

The odds against being

attacked

by a shark are nearly as long, but the issue here is as much semantic as statistical. Very, very few encounters between swimmers or snorkelers and sharks result in what could be considered an actual

attack

.

I think of an attack as what a grizzly bear does when she's protecting her cubs, or what wolves, bears, and even rats do when they're cornered or threatened. In general, sharks do not attack people; the exceptions happen mostly to scuba divers who unwittingly venture across an invisible line that a shark considers to be its territorial border and then either don't see, don't understand, or choose to ignore the obvious warnings issued by the shark.

When a shark feels threatened or crowded, or when it senses that its territory is being violated, its posture changes; its back hunches; its pectoral fins drop; sometimes it shakes its head back and forth; always it looks and acts agitated. It is sayingâbroadcasting,

shouting

â“Get out of here! This is

my

turf.” Fish get the message; they scatter and disappear into the reef. People sometimes don't, with the result that the shark attacks: it rushes in, bites, and, usually, retreats to wait and see if the intruder withdraws.

For the most part, what we're talking about when we use the words

shark attack

are really shark

bites,

one step in the shark's normal feeding pattern, motivated not by rage, fear, or frenzy but by curiosity, confusion, and hunger.

Semantics aside, the chances of your being bitten by a shark are ridiculously small. If you added up the shark-bite incidents reported around the world in a given year and divided the total by the number of man-hours spent in the water, you'd get some unfathomable figure like .000003, which would enlighten you not at all.

But if you swim in the sea, there does exist a tiny chance of your being bitten by a shark. The good news is that there are ways to reduce that chance to very close to zero.

Over the past twenty-five years, in the United States and many other countries around the world, there has been a vast shift in population toward the seashore. In the U.S. alone, some 50 percent of our 280 million people now live within fifty miles of the shore. Millions of people who did not grow up near the sea and who know nothing about it are now exposing themselves to the sea, with all its beauty, power, mystery, and danger.

Many are venturing into the sea without according it respect for what it is: the largest environment on the planet, home to more animals than any otherâall of which must eat in order to survive. It is an environment in which most of us are not only aliens but also clumsy and ill-equipped to survive.

And yet on every glorious day of every summer, men, women, and children around the world plunge into the sea, taking risks that they shouldn't ⦠most involving drowning but some involving creatures that sting, pinch, and bite. Including sharks.

That's why I believe that practically no shark bite is unprovoked. We provoke sharks simply by going into the water, entering their feeding grounds, becoming fair game.

There are some practical steps to take to reduce the risk of shark bite, and the first requires a bit of a change in one's worldview, a shift of focus from the utopian to the real.

These days, most of us are so rarely in danger from anything in nature that we've become complacent. We assume we're safe everywhere. Australians are an exception, because they're brought up to

know

that their lovely nation is home to innumerable dangerous living things. The rest of us have been conditioned to Bambi-ize the animal kingdom, so we tend to regard every animal as warm, cuddly, and friendly, or, sometimes, simply afraid of us. So little are we exposed to wild animals that we have no real knowledge of how to behave around them.

On land, our ignorance is rarely tested: deer eating flowers in the backyard aren't a threat to life and limb. But when we choose to venture into the sea, we can't afford to be complacent. Among the many millions of creatures living there is the world's only large, free-roaming predator that poses a genuineâand sometimes mortalâthreat to man in an environment in which he freely chooses to go: the shark.

And sharks can be anywhere: in shallow water or deep, in the surf itself, even, occasionally, profiled against the face of a breaking wave. They can be in the little dips between the shore and sandbars just offshore, where low tide sometimes traps them. They can be in murky water or clear, rough water or calm.

Furthermore, while only a few species of sharks are considered dangerous to man,

all

sharksâespecially all sharks over three feet longâshould be respected and avoided by swimmers. I've been hassled by a school of three- and four-foot-long sharks, and what began as a game of push-and-shove soon turned into a terrifying mass mugging from which I barely escaped, with bite marks on my fins.

Before you enter the water, stand for a moment and look at the sea around you. If there are birds working offshoreâswooping and diving into a school of baitfish on or near the surfaceâthat's a sign that larger predators are underneath, driving the baitfish upward.

Perhaps those predators are bass or bluefish, but perhaps a shark or two could be stalking the bass or bluefish. Any signs that schools of fishâof any sizeâare in the neighborhood can indicate the presence of sharks. If you see a concentration of ripples on the surface of the water, or silvery flashes as feeding fish roll out of the water and their scales catch the sunlight, or a patch of action anywhere in an otherwise calm sea, don't go in the water. Nature's food chain is in process, and there's a chance that the apex predator that inhabits the very top of that chain is out hunting, too.

Don't go in the water if you're bleedingâat all, from anything, anywhere on your body. The same salt water that may heal your cut or wound will carry away the scent of your blood. The sensory apparati of sharks are so finely tuned that they can receive and analyze the tiniest bits of blood imaginable and can direct the shark to home in on the source of the blood from far, far away.

Blood is not the only attractant that emanates from us humans; we emit sounds, smells, pressure waves, and electromagnetic fieldsâall of which a shark can detect. That shouldn't surprise you: you know that your dog or cat hears and sees in spectral ranges far beyond ours, so why shouldn't a shark? After all, sharks have been around, and very successful, for scores of millions of years longer than cats, dogs, and people.

Don't swim or surf in water near seal or sea lion colonies. The playful and alluring pinnipeds are the prime (and favorite) food source for, among others, great white sharks. A surfer on a board appears, when seen from below, indistinguishable from a sea lion that has come up for a breath of air. Great whites are, by nature, ambushers; they prefer to blindside their prey, attacking from below and behind, and with such speed and force that they sometimes bite through surfer

and

surfboard before they realize they've made a mistake.

Don't go swimming at dawn, dusk, or night. Many sharksâtigers, for exampleâcome into the shallows at night to feed. On some islands, locals swear that sharks can tell when six o'clock in the evening comes along, for that's when fins can be seen crisscrossing the bay or cruising along the beach. Dim light, furthermore, decreases a shark's vision, forcing it to rely on its other senses and thus increasing the chances of a random bite.

The same holds true for swimming in turbid or murky water. A shark may sense nearby movement of a warm-blooded animal that it can't see and may decide to bite as a test of edibility.

Don't swim alone, and don't swim far from shore or other people. As a lone swimmer you are vulnerable preyâand the farther you are from rescue if something untoward does happen, the lower your chances of survival.

Don't go swimming where people are fishing from boats. They've probably put bait in the water, or even chum, which is a mixture of blood, oil, guts, and fish bits. (Even if you're not set upon by a shark, you'll stink for days, especially your hair.)

Finally, and most obvious, don't go swimming in areas where sharks are known to congregate or feed: steep drop-offs, where tide and current sweep prey to waiting sharks; the passes in tropical lagoons where, every six hours, the change of tide brings new feeding patterns to the entire chain of wildlife in the water; channels into harbors, where fish are cleaned and remains tossed overboard by returning boats.

There are also a few don'ts for when you

do

go swimming.

Don't wear jewelry or any shiny metal in the water. It flashes and shines and can, in frothy or murky water, look to a shark like a wounded fish. A friend of mine went swimming wearing a bathing suit with a brass buckle. As he was wading out of chest-deep water, he felt something brush between his legs, and when he reached the beach he found that he'd been slashed open from thigh to kneeâby something with extremely sharp teeth, either a barracuda or a small shark, for he never felt any pain. If there hadn't been a lifeguard handy to put a tourniquet around his leg, he might have bled to death.

Another friend wore a gold cross on a gold chain while he was snorkeling. A shark rushed him from below, ripped cross and chain away, and, with the same slashing bite, tore open his chin.

Don't swim in the ocean with your dog. Dogs swim with an erratic, ungainly motion that can attract curious sharks.

And don't

you

make any erratic movements, either, such as splashing, kicking, or tussling with your buddy. All of those send out signals that say,

wounded prey ⦠worth investigating

.

Despite all these cautions, it's important to remember that no matter what you do, the odds are in your favor. Whether or not a person acts with vigilance and common sense,

still

the statistical chances of being set upon by a shark remain well within the comfort zone, somewhere between slim and none.

The most notorious face in nature: a great white shark, upper jaw dropped into “bite position.” In fact, though, this was a moment of curiosity, not aggression. The shark had poked its head out of the water and was just having a look around. South Africa, 1999.

© JENNIFER HAYES

A great white shark that circled our tiny boat several times off Gansbaai, South Africa, in 1999. When we boarded the boat, the captain said, “Rule number one: if anybody falls overboard and a shark grabs him, the person next to him jumps down onto the shark's head. That startles 'im and makes 'im let go. Usually.”

PETER BENCHLEY

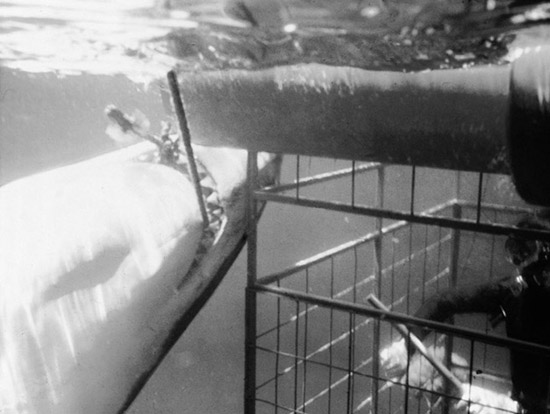

Nature's perfect creation: a great white shark approaching a bait (

top

) and eyeballing a diver in a cage (

bottom

). Essentially unchanged for tens of millions of years, great whites have no enemies except bigger versions of themselves, killer whales, and, of course, man. No one knows for sure how many great whites still exist, but the evidence, anecdotal and scientific, suggests that the magnificent animals are threatened everywhere and, in many parts of the world, actually endangered.

© HOWARD HALL/HOWARDHALL.COM

The shark approaches the cage and prepares to take a test bite.

© ABC SPORTS

After completing a circle of the cage, the shark comes at it from a different angle and lifts its head out of the water to swallow a bait.

© ABC SPORTS

Shark's view of me in the cage. Do I look appetizing? I don't think so.

© JENNIFER HAYES

My fantasy becomes reality: the first great white shark I ever saw underwater. South Australia, 1974.

© ABC SPORTS

The shark has snagged the tether rope in its teeth. Cowering in the cage, armed only with my trusty broomstick, I alone realize that chaos is about to ensue.

© ABC SPORTS

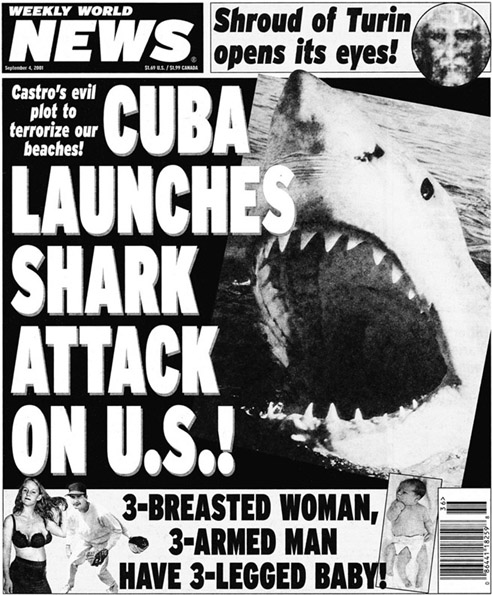

The summer of hypeâ2001. One newspaper's attempt to explain the supposed explosion in shark attacks on humans.

© AMERICAN MEDIA, INC.

A completely phony computer-generated image that was circulated on the Internet during the summer. No wonder shark-attack hysteria gripped the nation.