Shattered: The True Story of a Mother's Love, a Husband's Betrayal, and a Cold-Blooded Texas Murder (20 page)

Authors: Kathryn Casey

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #True Crime, #Murder, #Case Studies, #Trials (Murder) - Texas, #Creekstone, #Murder - Investigation - Texas, #Murder - Texas, #Murder - Investigation - Texas - Creekstone, #Murder - Texas - Creekstone, #Temple; David, #Texas

When she arrived, Shipley couldn’t stop thinking about what Mrs. Temple had said: “I just could not have raised a son who would kill his wife.”

“Is the husband a suspect?” she asked.

The others filled her in on what they’d seen, the shotgun blast to the back of Belinda’s head, and the physical evidence that didn’t match David’s story, from the ferocious chow that wouldn’t let a police officer in the house to the shards of glass indicating the door was open when the glass was broken.

The detective listened, thinking about Belinda, eight months pregnant, executed by someone cold and callous enough to put a shotgun to the back of her head and pull the trigger. Despite everything she’d seen in her years in law enforcement, Tracy Shipley wondered:

Could a husband really do that to a wife, to his unborn child?

L

ate that night, one of David’s uncles called Paul Looney, a Houston criminal defense attorney the uncle knew from church. Soon after David arrived home, Looney, a man with a high forehead surrounded by a fringe of white, a firm jaw and an expressive voice, hopped in his Porsche and drove to Maureen and Ken’s house on Katy Hockley Road, arriving sometime after 1:30

A.M

. He talked briefly to David’s family, and then was escorted outside to where David sat on a bench, his head buried in his hands.

When it came to Looney’s client list, most were relatively low profile, with the exception of a brief stint as the attorney of Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber, and one of the Branch Dividians caught up in the David Koresh case in Waco, Texas. At one point, Looney represented convicted sex offenders in their bid to better their chances of parole by asking for surgical castrations. Looney was used to cases being highly emotional, but he’d later say that the Temple case seemed even more so, and that when it happened it “rocketed through the Temple family.”

In the dark, cold backyard that night, Looney asked David’s brother, who’d accompanied him, to leave them alone, and then talked to David briefly, telling him that it wasn’t a good time to discuss the case fully, but that he didn’t want him talking to police without him from that point forward. “Don’t say anything precipitously. Don’t do anything precipitously,” he ordered his new client.

David agreed, but seemed preoccupied. Looney couldn’t seem to get him to focus on what he was saying, and he worried that David wasn’t getting the message. “He had an overwhelming concern for what he would tell his son,” remembers Looney.

On his way back through the house to leave, the defense attorney listened to Maureen and Ken Temple’s account of their encounter with the detectives at Clay Road, saying that Leithner had told them, “You need to get used to the idea that your son killed his wife.”

That sent Looney to the backyard again, this time to ask David if detectives had accused him of murdering Belinda.

“He confirmed that had happened, repeatedly,” Looney would say later. “At that point, I told him no polygraph.” Looney made arrangements for David to meet him at his office early the following morning, and then left the house. Later, Ken would say that none of the family slept that night, and he’d describe his son as stunned, as if in shock.

The first

Houston Chronicle

article on the murder bore the headline: P

REGNANT

W

OMAN

F

OUND

S

HOT

T

O

D

EATH

I

N

H

ER

H

OME

. The reporter said that David M. Temple told deputies that he’d returned home to find the body of his wife, Belinda, about 5:40 that afternoon, in the bedroom of their house. Belinda was described as a popular teacher at Katy High School, and it was noted that the School District planned to bring in counselors to work with the faculty and students.

Heather was the first one up at the Perthshire-Street town house that morning, but by the time the phone rang, Tara was getting ready for school. Heather picked up the telephone and talked to a friend, who told her to turn on the television and watch the news. She did, and moments later, Heather and Tara saw the reports of Belinda’s murder. In some of the news footage, David could be seen sitting in the back of a squad car. “Heather became hysterical,” says Tara. “She cried, ‘Oh, my God,’ and got extremely distraught.”

Also up early that morning, Debbie Berger arrived at Katy High School and found the principal in the midst of a meeting with counselors and a few of the teachers. Berger poked her head in the office to listen, but was there only moments when she began to cry. The other teachers gathered around to console her. “I felt like all of us were grieving and at the same time in a state of disbelief,” she says.

Before school began, the school psychologist talked to Debbie and Cindy, the teachers closest to Belinda. Both were crying and upset, but then many were on campus that morning, as students arrived with tears in their eyes. “The kids wanted to know who would do such a horrible thing,” says Debbie. “We couldn’t tell them.”

Meanwhile, at Hastings that morning, an e-mail went out to the staff from the principal: “Give our sympathy to Coach Temple. His wife was brutally murdered last night.” There were many whispers that day on the campus, much of it about David, as his coworkers wondered if he was behind Belinda’s murder. When Heather showed up, she went to the principal’s office and spent much of the day there.

At the Alief field house, where David officed, early that morning, a teacher’s wife called to try to find out if anyone had talked to David. One of the other coaches, Mike Slater, answered the telephone. He sounded upset and said that he’d only heard about the murder on the news that morning, on the car radio on the way to work.

Later, the woman would recount her conversation with Slater, a conversation the coach, who was a good friend of David’s, would deny took place: “Mike Slater said he couldn’t believe that it had happened. Then he said that David must feel really awful, especially since when David had to leave school early to take care of Evan that afternoon, he was cussing Belinda up and down. David was furious with her.”

At the Temples’ house, Ken would later say, the day began with David going into Evan’s room to tell him of Belinda’s murder. Later, David would say he lay down beside the toddler and told him that “some bad men had broken into the house and momma’s heart stopped, and that she’s gone to be with Jesus, and she won’t be with us anymore.”

Later, a relative would say that Evan asked a lot of questions, including a recurring one: “Why isn’t Mommy here?”

Afterward, David arrived in Paul Looney’s seventh-floor office, off the Katy Freeway, with his parents and brothers. It would seem that the family often did things as a tribe, but the defense attorney asked to talk to his client alone. Behind closed doors, Looney still had a hard time getting David to focus on Belinda’s murder. All David wanted to talk about were concerns about Evan.

What David didn’t appear worried about was the investigation. He barely seemed interested in anything Looney had to say about what police might be doing. Still, there were things Looney needed to ask. Some defense attorneys don’t want to know if a client is innocent or guilty, believing that knowledge can tie their hands in the courtroom. For instance, codes prohibit an attorney from putting a client on the stand if they know he or she will lie.

“I tell my clients that the only thing I want is to keep them out of trouble,” says Looney, with all the certainty of a convert preaching the gospel. “I don’t give a damn if they did it or not. I don’t approach a case any differently if my client is Charlie Manson. I have a moral calling to keep everybody out of cages…. But don’t let me be surprised with the evidence.”

The defense attorney would say that years earlier he’d used that same speech on Timothy McVeigh after the Oklahoma City bombing, and McVeigh, without hesitation, told him of making and planting the bomb. “I can be very persuasive,” says Looney.

It was after such an impassioned introduction, Looney would say later, that he asked David if he’d murdered Belinda. “David said, ‘Of course not, and I’m not sure I can keep you working for me if you’re going to keep asking that kind of question.’”

Early that morning Ginny Wiley drove to Katy High, where she’d graduated a year earlier, to see her old teachers. She felt alone and needed to talk about the murder. At the school, Ginny listened to the morning announcements, at the end of which the principal told the students about Belinda’s death. Some of the teenagers cried, and many hugged and held hands.

Afterward, Ginny drove home and changed clothes, then bought flowers. She drove to Round Valley, where police cars were still out on the street and an officer sat in his squad car watching the scene. It was a windy day, and Ginny bent down and put her flowers with others that were collecting in front of David and Belinda’s house. They blew away, and she ran after them and replaced them. Then she stood on the street and looked up at the redbrick colonial Belinda had been so proud of, sadness surrounding her.

Others made the same pilgrimage that Tuesday, including Tammey Harlan and Kay Stuart, the wife of Hastings’ head football coach. They laid their flowers beside the others, and throughout the day the memorial grew, some with small notes written by children on the block and Belinda’s friends.

Something about this particular murder touched so many; perhaps it was the memory of Belinda’s enthusiastic smile or the thought of an innocent infant who would never be born. When Detective Tracy Shipley thought about why it touched her, she thought of all the cases detectives handled where the victims were known to be at risk by their families and friends, victims involved in drugs or crime. Belinda wasn’t someone who’d lived a risky lifestyle that would have portended a violent death. “Her murder pretty much killed everyone’s innocence,” says Shipley.

At 7:30 that morning, Detective Chuck Leithner received a call from the medical examiner’s office. Belinda’s autopsy was scheduled for nine. It’s not unusual for homicide detectives to attend autopsies, to collect evidence and hear firsthand the impressions of the physician. Leithner called his partner, Mark Schmidt, and made arrangements to meet him at the county morgue, a commonplace-looking brick building not far from the miles of hospitals that make up Houston’s Texas Medical Center.

When they arrived at the Joseph A. Jachimczyk Forensic Center, on Old Spanish Trail, Dr. Vladimir Parungao, the assistant medical examiner who’d conduct the autopsy, told them that Belinda’s body had already been examined under ultraviolet lights, searched for hair and fiber evidence. When they walked into the morgue, her naked corpse lay on a metal gurney in an autopsy suite, the right side of her face a gaping, bloody, raw hole. Two bags held other evidence, including brain matter, her broken glasses and the lead shot fragments from the shotgun shell. The clothes she’d worn that final day rested on a tray underneath the gurney. Although he’d seen much in his years in law enforcement, Mark Schmidt looked at Belinda’s body, swollen in the final month of pregnancy, and felt overwhelming sadness.

As Parungao examined the body, he pointed out bruising on Belinda’s knees, consistent with her having been in the position Holtke and Rossi suggested, crouched down, perhaps kneeling at the time of the fatal shot. Examining the body, Parungao measured her hair, twelve inches long, and noticed Belinda had lividity, the settling of blood by gravity, on both sides of her body.

“She was rolled over?” Parungao asked the detectives.

“Yes,” they confirmed. “We rolled her over at the scene, when the assistant M.E. arrived.”

That settled, Parungao made the initial incision into the body, a “Y” cut, starting at the clavicle and, at the end of the sternum, straight down through the abdomen. Once he’d spread the skin back, he examined her internal organs. Belinda was a healthy woman, only thirty years old, and he found nothing out of the ordinary, until he reached her abdomen.

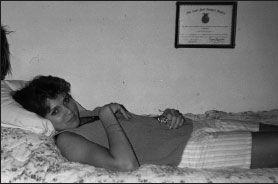

The Lucases had nearly given up on having a girl when the twins were born.

Clockwise from left

: Tom Lucas, Brian, Carol, Barry, Brent, Belinda and Brenda.

(Courtesy of Brenda Lucas)