Shattered: The True Story of a Mother's Love, a Husband's Betrayal, and a Cold-Blooded Texas Murder (23 page)

Authors: Kathryn Casey

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #True Crime, #Murder, #Case Studies, #Trials (Murder) - Texas, #Creekstone, #Murder - Investigation - Texas, #Murder - Texas, #Murder - Investigation - Texas - Creekstone, #Murder - Texas - Creekstone, #Temple; David, #Texas

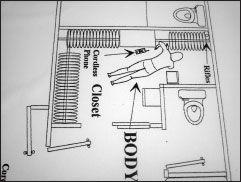

Another exhibit, this one a diagram depicting the position of the body in the closet. (Photo by Kathryn Casey)

Mark Schmidt had been in the delivery room when the younger of his two daughters was born, and it was a “fantastic moment.” He would never put behind him the memory of Parungao cutting through Belinda’s cold uterus, opening it up and bringing forward the corpse of a perfectly formed baby girl. Erin was eighteen inches long and weighed six pounds. The umbilical cord was still attached to the placenta, but the baby was ivory white and eerily still. The sight of the dead infant made Mark Schmidt shudder.

From that day forward, Schmidt would say, “I could never forget it. We want to solve every murder, but what made Belinda Temple’s death stand out was the baby.” Even years later, Schmidt would tear up at the memory of that day.

After extricating the dead baby from her mother’s womb, Parungao took a blood sample from Erin’s heart to run tests on, including paternity. Could the baby somehow be a motive for Belinda’s death? Was there another man in her life? The blood tests could answer those and other questions.

Leithner and Schmidt remained nearby watching, as Parungao then turned his attention to Belinda’s neck, examining her hyoid bone, at the base of her throat. The bone remained intact, suggesting that she hadn’t been strangled.

With that, he turned the body over, and inspected the entrance wound at the back of her head, on the left-hand side. To gauge the size of the bullet hole and examine it more closely, Parungao stitched together the area around the wound, reconstructing the hole, four inches below the midline of her head. The wound, the physician estimated, was three quarters of an inch in diameter, a contact wound. Belinda’s murderer had pressed the gun against the left backside of her head and pulled the trigger.

When Leithner assessed the wound, he concurred with Parungao’s assessment; gunshot residue in the wound suggested to both the detective and the physician that the shotgun had been flush against Belinda’s skull.

With Belinda’s body again on its back, Dr. Parungao examined the exit wound. The damage to Belinda’s face was catastrophic. As it entered, the force of the blast had shattered much of her skull, emptying it and blowing out the right side of her face, centered on her eye. Belinda’s teeth were still in place, but her jaw was broken. “The cranial cavity was empty of any brain tissue,” the physician noted. “The blast shattered the entire cranial cavity…. The brain exited on the right side of the face.”

On his report, Parungao listed his conclusions. First: the trajectory of the blast was left to right. Second: the cause of death was a contact wound to the head. Third: the manner of death was homicide. Based on the size of the wound, the diameter of the contact area, the murder weapon was a .12-gauge shotgun.

The autopsy continued, and Schmidt stayed with the coroner. Meanwhile, Leithner took the elevator to the fifth floor, bringing with him the remains of the shotgun shell recovered from the scene and the body. Once there, he met Matthew Clements, a firearms expert. Carefully, Clements examined the wadding and lead fragments. Based on the weight of the pellets, it didn’t take Clements long to evaluate the type of shell used. “It was double aught, not birdshot but buckshot, a type of shell used for hunting deer,” says Schmidt.

There was something else about the shell’s remains. Examining the wadding and pellets and comparing it to samples he had, Clements was able to determine that the shotgun shell wasn’t factory manufactured but rather a reload, a recycled cartridge that had been refilled with pellets and wadding for reuse. Even more interesting, the wadding was of an unusual type, one Clements had never before come across.

“We now had an idea of the murder weapon and the shotgun shell,” says Schmidt.

The first morning after the murder turned out to be a hectic one for the detectives on the case. As they finished at the M.E.’s office, a call came in. Paul Looney had faxed a letter withdrawing consent to search. That meant that the sheriff’s department no longer had permission to process the Round Valley house, now known as the Belinda Temple murder scene. Assistant D.A. Ted Wilson had already been notified, and he wanted Leithner in his office to help write a search warrant. While within David’s rights, withdrawing permission made the prosecutor and investigators look even harder at him. Says Wilson, “I’d never known anyone who’d done that who didn’t have something to hide.”

At the D.A.’s office late that same morning, Wilson listened as Leithner detailed the discrepancies between David’s statement and the evidence at the scene, including the broken glass and the dog that wouldn’t let police enter the yard. The detective thought that perhaps he had enough evidence to book David while they continued the investigation. The prosecutor wasn’t swayed. “What Detective Leithner told me was highly suggestive that the victim’s husband was the killer,” says Wilson. “But to take it into a courtroom, I needed more evidence.”

At Tiger Land day care that morning, the teachers gathered, many upset, talking about the news reports. “Her husband did it,” one said.

Another replied, “Do you really think so?”

“I know he did,” a third said.

When the mothers and fathers came in, many were curious about David as well. Some remembered him from his years as a student at Katy High, where stories of bullying and violence circulated about him. Still, everyone’s primary concern was the children. The teachers were cautioned not to show emotion. Most made it through the morning, but by break times, some sat in the lunchroom, their heads on the table, crying.

After interviewing his client and pinning down his alibi, Looney called Wilson. David had told his defense attorney that he had left the house the evening before and gone first to the park, then to a Brookshire Brothers grocery store on Franz Road, followed by a stop at the Home Depot on the Katy Freeway. Looney figured both of the stores had surveillance cameras. “I knew the cameras were probably on a loop, and I wanted the prosecutor to get them before the tape was erased,” says Looney. “I didn’t want them to be lost.”

Looney also put something else in action that morning. He called Mark Hatfield, Ph.D., a psychologist who specialized in treating children. David was worried, concerned about Evan and how to handle his grief and confusion over his mother’s death. Hatfield said he would see the toddler and made an appointment for David to bring him in that afternoon.

At the Round Valley house that morning, all work had stopped.

The CSI officers had predicted that would happen.

Early that morning, David’s brothers, Darren and Kevin, had shown up twice, the first time wanting a prescription medicine and a jacket for Evan and a suit for David to wear to Belinda and Erin’s funeral. The next time they’d come looking for Evan’s bike, a yellow two-wheeler with training wheels that Holtke had to get down off hooks from the garage ceiling. Holtke had followed orders and given them what they were looking for, but saw one of the brothers in the garage writing down the VIN numbers off the Isuzu and David’s blue pickup truck. In Holtke’s opinion, it seemed like David’s brothers were on a fishing expedition, looking around to see what the crime-scene investigators were doing.

So when the sergeant called around 11

A.M

. to say the consent to search had been revoked, Holtke shrugged as if it were expected. As ordered, he and Rossi vacated the house, standing out on the street, guarding the property while they waited for Leithner to obtain a search warrant. An hour later, the confirmation came in. Holtke and Rossi walked back into the house, this time under the authority of a search warrant signed by a judge.

The work resumed at 22502 Round Valley. In the laundry room Holtke collected a shirt, one with a golf pattern they’d call the “rules of golf” shirt. On the front they saw a spot that resembled blood. They bagged the two Post-it notes from the kitchen counter, the one documenting when Evan had his last Motrin and the note asking Belinda to call her aunt. In the master bedroom, Rossi claimed as potential evidence a gray warm-up suit, including the jacket, which had been draped over the back of a chair, just inside the door. The reason it caught his attention was that the matching pants were on the bed, as if David had just taken them off. The damp towels, too, went into an evidence bag, and a call was put out to a serology expert, asking her to respond to the scene to test for blood evidence that might have been missed.

The crime-scene unit worked throughout the day. That afternoon Dean Holtke and David Rossi threw finely ground black fingerprint powder, covering the doorways, doorknobs, parts of walls, and much of the back door with the broken glass, hoping to find a clue to the identity of the killer. At the morgue, Belinda’s fingerprints had been recorded. In the end, many of the prints found in the house were small, indicating they’d come from a child, presumably Evan, and all the others tied back to David and Belinda.

In the garage, Rossi processed the Isuzu, taking into evidence the Home Depot bag. At the back door, Holtke saw a pair of tennis shoes on the patio and bagged those as well.

When the serology expert showed up late in the afternoon, she sprayed luminol, a chemical made of nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen and carbon. When mixed with hydrogen peroxide and lit with an ALS, an alternative light source, in a darkened room the chemical glows when reacting to iron found in blood. Holtke and Rossi went through the house, pinpointing areas to test. The “rules of golf” shirt they’d bagged in the laundry room tested positive, and upstairs in the master bedroom, Holtke asked the woman to spray the backs of the mirrored doors on the closet, looking for blowback from the shotgun blast. Although sections of the closet glowed when the ALS was turned on, including the wall in front of where Belinda’s body had lain, the backs of the doors, where blowback should have been found, didn’t react. There was no indication that the blast had scattered blood and brain matter behind Belinda, in the direction of the killer.

“Our thought was that the blowback was small and, if the shotgun was tight against the victim’s skull, it would have been sucked up back into the barrel,” says Holtke.

In the bathroom, however, another area did react. When the serologist sprayed luminol in the sinks, one drain glowed. When Holtke dismantled it and removed the P-trap, the U-shaped pipe below the drain that fills with water to prevent sewer gases from entering a room, it, too, lit up with luminol exposure. He bagged the pipes to be sent in for more testing.

As they searched, both Rossi and Holtke knew the importance of the evidence, especially if it turned out that a stranger had broken into the Temple house and killed Belinda. Unexplained fingerprints or blood could point to a possible suspect. On the other hand, if David was the killer, they also knew that forensic evidence could be difficult. In domestic homicides, where both victim and killer live in a house, it’s not surprising to find their fingerprints and DNA present. It would be more unusual if they didn’t leave behind evidence of their presence in the form of fingerprints, hair, fibers, and DNA, even blood.

At the district attorney’s office, Wilson met with another of the A.D.A.s, Donna Goode, a tall, thin woman with long dark hair. Goode, who’d been born on Galveston Island, had been a social worker before law school. While they worked on the search warrant, Leithner and Wilson had discussed Evan, wondering if the toddler heard or saw anything during the murder.

“I’d like to get the boy to give a statement,” Leithner suggested.

Wilson thought it over, agreed, and called Goode, who as a social worker had worked with children. In the past, Goode and Wilson had worked closely together, including on the Laura Smithers case, that of a twelve-year-old girl who disappeared while jogging not far from her home. Wilson thought they complemented each other well, that he was better at the big brush strokes, while Goode worked well with details.

While Leithner was at the D.A.’s office, Schmidt returned to homicide on Lockwood to make phone calls. His first was to Precinct Five constables’ office, where he asked for a copy of all the dispatch tapes for the officers who’d made the scene the evening before. Afterward, he called the 911 telephone center and asked for tapes of David and Peggy Ruggiero’s calls. He picked them up and brought them back to the Lockwood station, where a group of the detectives gathered around, Shipley among them. On the 911 call, they heard David talking to the dispatcher and then the EMT, who tried but failed to convince him to give Belinda CPR for the sake of the baby.

The first time they listened, it was hard for the detectives to take it all in, so they played the tape a second time. It was then that they noticed David fluctuated from sobbing to sounding calm, and how he stressed that the back-door glass had been broken. “It was like he was saying, ‘You stupid cops. Don’t miss this!’” says Shipley.