She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me (10 page)

Read She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me Online

Authors: Emma Brockes

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Adult, #Biography

I have no expectation of finding anything. That the numbers in my notepad might correspond with a physical object in this building or in the vaults under it seems to me as improbable as stumbling on a message in a bottle which, when unfurled, has your own name upon it. Not just your name, but your family's darkest secrets, typed up by a third party and signed by witnesses. It seems outrageous that such a thing might exist, under cover of neutrality, on cool, indifferent paper and on a shelf with other papers just like it. Calmly, I sit and wait, and while I wait, I watch these quiet, elderly people grazing over open ledgers. Some of them have put on ties and jackets to come here. Good, kind people, I think, researching their family trees to pass on to their grandchildren and redeem in themselves a sense of continuity and purpose.

The first shock is that a file matching my request comes up from the vaults. The second shock is logistical. When I walk over to the table and find it, I see that photocopying it will be out of the question. It's a huge ledger, labeled on the spine with a single year and containing every court case heard in the district in that period. It's too overstuffed to fit on the copier. I haul it back to the table and, looking at the clock, see I have two hours to transcribe by hand whatever I find.

I have no month to go by and start paging through from the beginning. It is like playing a game of Russian roulette, each page containing the split-second possibility of an explosion in my face. A couple of breaking and enterings. A Mrs. Potgeiter molested in her own home. A long legal debate on what does and does not constitute rape. Mrs. Potgeiter's assailant got twenty-five years, but he was black, and it becomes apparent, after thirty or so pages, that the only successfully prosecuted trials were ones such as this; the legalistic relish for the black man attacking the white woman rises up off the pages like mist. I am so engrossed in Mrs. Potgeiter and her troubles that when, three-quarters of the way in, I turn a page and see my mother's name, I don't keel off my chair, but take it as more or less part of the continuum.

Three words leap out of the summary page: “incest” and “not guilty.”

My mother never used that first word. I've never used it even in my head. I look up to see if anyone is watching me. I look down at the page again.

I take in the name of the prosecutor, Britz, and the defendant, acting “for himself.” The case has been brought, I see, not in my mother's name, but in my aunt's. Of course. At twenty-four, my mother was too old to be medically useful. I do the math. Fay was twelve.

There is a faint cough. I look up to find a man in the national costume of his peopleâkhaki shorts, khaki shirt, khaki knee-length socks with a comb tucked into themâcraning in my direction. In an avuncular sort of way he asks what I am doing here. “Family tree,” I say, and give him a look I hope communicates just how happy it would make me to see him go down, Leonard Bastâlike, in a shelving accident. “Well, if you need any help,” he says, and writes his e-mail address on a scrap of paper.

I return to the ledger. It takes me a few moments to figure out what I am reading. There seem to be two charge sheets and two cover sheets recording verdicts from two different trials. In one, my grandfather is found guilty; in the other, not guilty. They are separated by a period of several months. I finally figure out what this signifies: the passage of the case from its preliminary hearing at the local courtâthe South African equivalent of a grand jury, held to determine whether there is sufficient evidence in the case for a full criminal trialâto the High Court in Johannesburg. He was found guilty at the first hearing and not guilty at the second. I flip the pages back and forth. Guilty/not guilty. Guilty/not guilty. On such words entire life histories turn.

I flip the page and the first hearing begins. There is a list of witnesses, with my mother's name near the bottom. I see that her youngest sister, then seven years old, was required to appear as a witness. Her brother Tony is on the list, and her sister Doreen, but no sign of Mike. Her stepmother is the first witness.

A few pages in there are two sets of diagrams, cross-sections of the human body, beneath the names of the twelve- and the seven-year-old, with arrows alongside which a court surgeon has signed. It takes a moment for me to make sense of them. Oh, injuries. I look up from the page.

Over the next two hours, I transcribe the notes, shoulders hunched, hand cramping, brain disengaged. I don't process much beyond the necessity of copying. It is a physical exercise. When I get to the end of the first trial, I turn a page to find a sheaf of shorthand notesâthe original court records. I get to the end of these and there's nothing more. I look and look again. There are no records from the second trial. It will be impossible to tell how the testimonies changed. (Later, to be sure I hadn't missed anything, I employed a researcher with shorthand skills to go to the archive and translate the notes at the back of the file. She e-mailed me the findings and, as I suspected, they simply duplicated what I had. “What a terrible thing,” she wrote in her note. “My heart broke reading this. Who could do such a thing to children?” I hadn't owned to the family connection and was mortified, both to see it reflected like this in a stranger's reaction, and to have put this nice lady through an ordeal. “Yes,” I replied. “It is awful, isn't it.”)

After returning the ledger and packing up my things, I leave the reading room, cross the car park, and to the concern of the guards in the booth, say I am going for a walk. I turn left and blindly climb a hill, which it turns out leads to the parliament buildings. These are large, classical structures with a panoramic view over Pretoria. Opposite is a small garden, behind a chain-link fence. I step over the fence and sit on a bench, looking out over Pretoria in the direction of Johannesburg. There are large red flowers, which I think I recognize as protea; I've seen them illustrated on Joan's airmail letters. Flightless birds hop about on the lawn.

I am exhilarated. I have read the contents of the file and yet here I am, alive, sitting on a bench in the afternoon sun. I experience a surge of vindictive triumph and conduct a long exchange in my head with the dead man, who I don't permit to speak. “Right, you fucker, you can answer to me.” This is mine, all of this. I am driving it now. “You have to own it”âone of those phrases in the therapeutic lexicon I have always despised, but which suddenly seems apt. I will own it so hard it breaks apart in my hands.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

ON THE WAY BACK

to the hotel I ask Paul to make a detour. From the court papers, I have addresses for the family going way back, including the place where my mother lived in Johannesburg at the time of the trial. It was here, during the course of one afternoon, that she resolved to carry on living.

“Do you know where Soper Road is?”

“Soper Road?” says Paul. He looks at me through the rearview mirror.

“Yes.” He carries on staring, so I add, “Someone I knew used to live there.”

We drive through the city in his air-conditioned BMW, around people pushing huge, baled loads, men selling cigarette lighters and smaller things from the depths of their palms, children running about in T-shirts that look as if the holes in them are holding up the fabric, like a viaduct. Paul hits the central-locking button with a flamboyance designed, I think, to enforce my sense of dependence on him.

At the corner of Wolmarans and Twist the names become familiar, not because I've been here before but because they borrow from London. The mansion blocks, great 1950s monstrosities, bear faded signs that read “The Hilton” and “Park Lane” and “The Devonshire” and then, incongruously, “Graceland.” Their windows are broken, stuffed with newspaper and front-loaded with balconies groaning under bits of trashed wicker furniture. It is as after a flood, when the water has drained, leaving tidemarks up the wall and the furniture stacked, teetering, in corners; the work of an angry poltergeist.

“What number?”

I peer through the window and count them down. The numbering is erratic. Either the place has been demolished or the street at some point renumbered. We park approximately where it should have been, and Paul glances nervously in his mirrors. I wait for something to happen, for my heart to respond to the moment or for my body at least to override the air-conditioning and break into a sweat. “I don't think you should get out,” says Paul. I had thought that grief, like cat litter, had no secondary uses, but there it is. Blankness.

“OK. Let's go.”

When I get back to the hotel, I go straight to the business center. The name of the judge at the High Court seemed familiar. I feed his name into a search engine and stare at the results. I feel sorry for all of us, then, shameful bit players on the periphery of history. Six years after acquitting my grandfather, this man had, briefly, become the most famous judge in the world. In 1963, while the world watched, Justice Quartus de Wet presided over the Rivonia treason trials at the High Court in Johannesburg, at the end of which he sent a young Nelson Mandela to Robben Island for twenty-seven yearsâa piece of exceptional leniency, it was thought at the time, since he was expected to be given the death penalty.

“Oh, love,” says my dad when I ring him from the room. “If you want me to fly out, I'll come tomorrow.”

“No, it's OK. I'm OK.”

I type the afternoon's notes into my computer. I don't look at them again for three years.

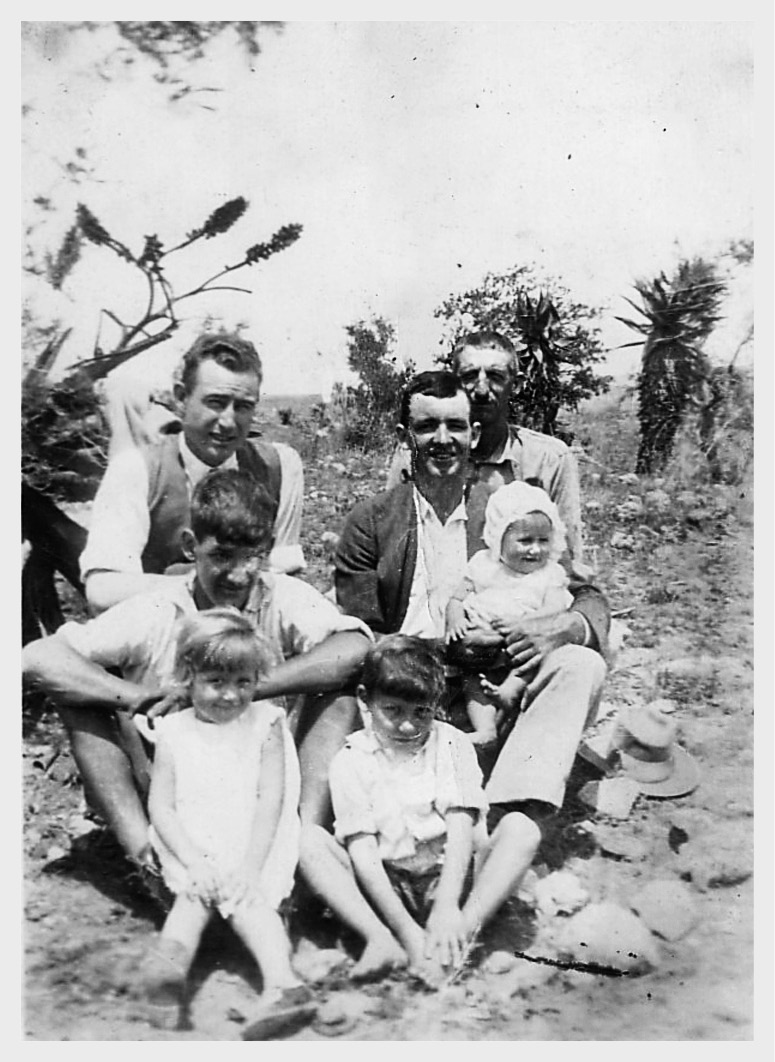

Hot and uncomfortable: my grandfather, back row, far left, with his in-laws, my grandmother, Sarah's, family (including her niece, Gloria, in the bonnet).

A Very Interesting Group of People

MY MOTHER'S FATHER

looks relatively normal in photos. There he is, sitting in a group surrounded by members of his new wife's family: her brother-in-law Charlie, and her nieces and nephews. Jimmy looks young, slightly sheepish, perhaps, or shy. They are sitting on a patch of dust in rough clothing, a few parched sprigs of vegetation behind them in what the back of the photo identifies as Zululand. They look hot and awkward, as if they have just stepped off the boat.

In fact, the DeKiewits, my grandfather's family, had been in the country since the turn of the twentieth century, when they emigrated from Holland. My grandmother's family had much deeper roots in South Africa. Their name was Doubell, which it pleased my mother to think of as French, although she must in her heart have known better. I'm not in South Africa long before I notice with a shock that Doubell, like other French-sounding names in those partsâRoux, Terreblanche, Joubertâis Afrikaans by association. My grandmother's ancestor might have come from France a hundred years earlier, but her mother was a Van Vuuren and her grandmother was an Oosthuizen, and whichever way you slice it, those are not French names.

My grandfather was born in Johannesburg to first-generation European immigrants, which put him higher up the social scaleâa whiter shade of whiteâthan his young wife, although in any other immigrant community, as the newer arrival, this would not have been so. His family were poor, resourceful, ambitious, multichild-bearing, and given the nature of the country they had moved to from the security of Holland, deeply eccentric. By the time my mother was in her mid-twenties, the family name had become somewhat famous. She used to tell me about this with a mixture of pride and anxiety. Her father's first cousin Cornelius, with whom her father had grown up and who bore the same surname, was in the newspapers a lot in the era. He was a historian with stout antiapartheid views who after leaving South Africa for England had found tenure at a liberal arts college in the United States.

Not long before my mother emigrated, he visited Johannesburg from his home in upstate New York to deliver a lecture under the auspices of the South African Institute of Race Relations. My mother read about him in the newspaper and felt encouraged; if she didn't go mad or shoot herself, she thought, there was a chance someday she might amount to something. She longed to meet him, her father's illustrious cousin. But she hesitated to get in touch. She had been in the newspapers, too.

It is a strange quirk of history that, while I know none of my closer relatives, I know Cornelius's granddaughter Caroline. She is American; we became friends online and then met up when she was in London one time. It is thanks to Caroline I know anything at all about the world my grandfather grew up in: Cornelius wrote a short, unpublished memoir of his childhood, which she very kindly sent to meâand which, in spite of myself, I have raked through time and again, looking for clues; why, of the two boys who grew up next door to each other, did her grandfather became the successful academic and mine the murderer?

It doesn't get you anywhere, this kind of speculation, but there is a temptation to mine for small variables. Did one have an inspirational teacher, which the other didn't? Or suffer a bang to the head, which, I discovered during my brief obsession with serial killers as a teenager, got lots of violent men started?

There was the wider insanity of a country in which a white child was encouraged to believe that however badly he behaved, he was intrinsically more valuable than an entire race of people. As a pathology, it might have been designed to create psychopaths. But both boys were subject to that. The most there is in the memoir is a suggestion of favoritism. Cornelius, older than his cousin Jimmy by a few years, was a teacher's pet. He was good at Latin. The boys' grandfather, the dominant influence in their early lives, loved him very much and vested in him the hope of the family. Jimmy's father, Johannes, seems also to have been very fond of Cornelius. From much smaller things great resentments have prospered.

The family came to South Africa sometime in the 1890s. Gold had been discovered there in 1886 and the country started rapidly to modernize; there were good job opportunities for young men from Europe. Arie, Cornelius's father, had first considered going to Latin America, but there was the problem of language, and so he settled on South Africa.

For a few years he made good money, working on construction of the railroad to Mozambique. When the Boer War broke out, his loyalty to the new place was so strong that he fought for Paul Kruger against the British. He was captured and escaped at the same time as Winston Churchill was going through the same experience on the other side. After that, wrote Cornelius, his father looked on Churchill as a sort of inverted twin, fortune's favorite. He was very bitter about the divergent routes their lives took.

Arie's family was part of the problem, particularly his father, a notoriously difficult man. They lived on the island of Texel, off the coast of Holland and part of an archipelago extending all the way to Denmark. They had been fishermen historically and were now builders and laborers. When peace was declared at Vereeniging, Arie called on his family to join him, and the entire clanâhis brother, Johannes, his three sisters, their husbands, and his parentsâtook the three-week voyage to Cape Town. Arie was an adventurer, but what the rest of the family thought they were doing, these Low Country people, transplanting themselves from Holland to a ramshackle frontier town in the southern hemisphere is anyone's guess. They were devout Lutherans, so perhaps there was a masochistic need to be tested. In the case of Arie's parents, the journey itself was a sign of election: these elderly people left home at a time when they had already exceeded their own life expectancy. (That Arie had failed to make his fortune in the new country doesn't seem to have deterred them. This is the root of all catastrophe in the family: no one ever knows when to call it a day.)

To read of Arie's parents is to travel at warp speed from modern times to medieval. His father, Cornelius and Jimmy's grandfather, believed that if you dug up a field there was a chance you might dig up a devil with it. Like the Dutch who went to America two centuries earlier, the grandfather had a concept of “freedom” that valued one freedom only: the freedom to be a religious maniac. He was a fanatic whose fanaticism cost him every job he'd ever held. When he tried to be a grocer, he would serve only those he had seen in church, dismissing all others with the words “You were not at the service in church yesterday. Today I cannot be of any service to you.”

When he was a carpenter and a builder, he was fired from every work site for arguing with the foreman.

“Having known Grandfather,” wrote Cornelius, “I know that swearing only comes into its own in the Dutch language. Grandfather's swearing had grandeur; it had the quality of a thunderous sermon in a New England pulpit, blasting the congregation with its own sins. He swore indeed as he prayed, with the same intensity and earnestness.” (I looked up some Dutch swearing recently to see what kind of health it's in. Translations don't do it justice, I'm told, but “prick-biscuit,” “buddy-fucker,” “get cholera,” “ass-beetle,” and “Your mother's ass has its own union” are all happy locutions in the Dutch language.)

Cornelius remembered his grandmother as a tiny, hunchbacked creature with an almost epic ability to endure. She was from a family called Haringâthe Dutch for herringâand didn't want to emigrate, but her husband's will was greater. She had been a midwife who had seen twelve of her seventeen children die in infancy. She had a strong satirical streak, and long before her husband's death, took to wearing a black widow's cap around the house, to her children's delight. She shrank from her husband's fanaticism, a personality trait that long after his death would resurface repeatedly in his descendants.

Those three weeks at sea must have passed for the grandfather like an exercise in spiritual cleansing. What he took to be his soul thrilled to the open water with a force that in a different man might have been called lascivious. The only book he read was the Calvinist version of the Bible in high Dutch, and he sat on deck, taking it literally.

His wife sat elsewhere on the ship. She was at a serene stage in her endurance. She thought of her grandchildren and concocted scenarios in which her husband fell overboard and she returned to Holland, alone.

At some point, the grandfather opened his mouth to reassure her and for the briefest of moments saw something in his wife that frightened him, something that implied resources in this small woman that were not only withheld from him, but that were in some sly way pitched against him. He dismissed the thought instantly. The ship sailed on. In the rare moments he gave to considering her feelings, the grandfather rationalized that no matter how difficult the new country might be, it would at least dislodge the thing they didn't talk aboutâthe twelve coffins borne one after the other to the cemetery. The babies' caskets were small enough for him to carry in his arms. The larger ones he balanced on a wheelbarrow.

The country they found on arrival was still smoldering amid the ruins of the Boer War. Arie met them on the dock at Cape Town and escorted them to the train on which they would make the three-day journey across country to the city in the east, one of the newest and highest cities in the world, 6,000 feet above sea level.

“Arie, my boy!” The grandfather clapped his younger son on the shoulder. “And here we all are, together again!”

“Father.”

Arie suffered a moment's panic. On the platform beneath the blazing Cape sky were his hunched mother, his wan sisters, and their husbands in their northern hemisphere clothes. His father's cheer did nothing to reassure him; the old man was at his most ebullient when facing down doubt.

Then he saw his elder brother in a brown suit and with a mild expression, and his spirit surged.

“Johannes!”

“Arie. Meet my wife.”

A woman stepped forward, and Arie laughed and put a hand to her belly. “Congratulations! He'll be the first African child in the family!” (The grandfather took leave of barking at the porter to suffer his own, fleeting moment of panic.) Somehow they boarded the train.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

THIS IS HOW I IMAGINE

it went, although there is no eyewitness account. Cornelius was a baby and my grandfather not yet bornâalthough he was the first in the family to be a native South African. What is known is that Johannes, his father, was a thoughtful, gentle man; my grandfather was not brutalized as a child. (The tyrant was his uncle, Arie, who, like some deranged emperor, banned his wife and children from referring to him as “he” and, on dark winter nights, forbade them from lighting the oil lamps until he got home. They sat, recalled his son, shivering in the dark.)

Outside the house was a different matter. Gold-rush Johannesburg, like its American counterparts, was a place of casual violence and endemic alcoholism. In Holland they had been living in a painting by Whistler; now they were in a Hieronymus Bosch. The fires of the mine dumps burned day and night. The rhythmic shudder of the drilling sent dust up from the floor. They moved into a complex of wood-and-iron shacks to the north of the city, arranged around the focal point of the grandparents' two-room home, a corrugated-iron structure that the grandfather painted bright red, daubing the name of the family on the outside wall.

It was in these two rooms that communal family life took place. The floor was compacted earth, with a coal stove in the middle that burned all day to keep off mosquitoes. The roof was galvanized iron, which made life inside hot. Water collected in a rain barrel outside in the yard.

Slowly a life came together. The grandfather wouldn't learn English on a point of principle and Afrikaans seemed to him an absurd invention, but he was forced to acquire some basic Zulu to deal with the human traffic at his gate. Despite his lofty religious principles, his position on the black man was that he was unthreatening but essentially useless. His wife's fear annoyed him. It undermined his illusion of government in the house.

As best she could, the grandmother eked out a routine, sweeping and going to the market, where she conversed in Dutch and never learned a word of any of the languages of the country she now lived in. In the morning, she made Mazawattee tea. At noon, she switched to coffee. There was barley and brown sugar for breakfast, and brown beans and black molasses for lunch. Tapioca on Sunday. She made toffee out of condensed milk and unrefined black sugar. For birthdays there was coconut ice or flan.

Once a month she deposited a penny in a stocking behind the sugar tin; she was saving for her own funeral.

When her family congratulated her on the occasion of her fiftieth wedding anniversary, she said merely, “It is long.” Her air, wrote Cornelius, was one of “complete sadness.”

He did not feel this way about his childhood. It was poor, he wrote, but “to be a child in a family of generations, where welcome is taken for granted, is the supreme advantage of poor people: they communicate elbow to elbow.” There was sadness there, too, however. Cornelius was conscious of living in a family of ghosts; when he looked around the table, he thought of his father's twelve dead siblings in the cemetery in Holland.

It was into this world that my grandfather Jimmy was born. His father worked as a blaster in the mines. Johannes always smelled faintly of dynamite, recalled his nephew, looking back on those scenes of his childhood some fifty years later, from the comfort of upstate New York.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

WHEN A BOY

in the family turned six, it was the tradition to give him an air gun. One day, a man came to the gate, begging for work. He was bolder than most, and putting his hand on the gate, opened it and started to walk up the path. The grandfather, standing in the doorway, shouted, “

Voetsek!

”âa ruder version of “Piss off”âand Cornelius shot the man in the backside. It was only an air-gun pellet, but the man whipped around, stunned, and started back for the house. Cornelius ran and hid behind his grandfather, who at lunch that day gave a sermon about the sin of injuring one's neighbor. “Lord, thou hast seen the act of a sinner.”