She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me (13 page)

Read She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me Online

Authors: Emma Brockes

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Adult, #Biography

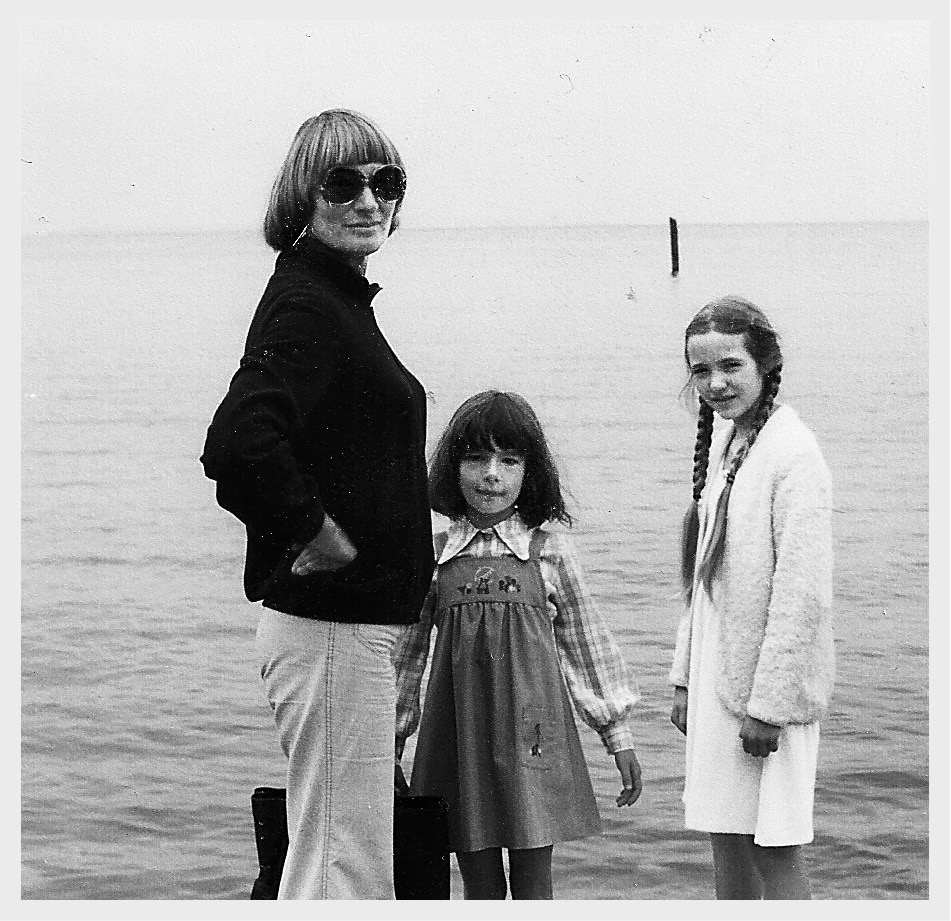

By the sea, early 1980s: Mum, me, and my cousin Victoria (with pigtails).

Everything That Matters

MY COUSIN PULLS

up outside the hotel in an off-white truck. “Sorry I'm late,” she says, jumping down. “I never come to this part of town.” She is in khaki shorts and shirt and Timberland-type boots. She looks at my feet. “Are those the only shoes you have?”

We are going dog training, Victoria and I, en route to her house, where Fay, her mother, is waiting. My cousin runs the course and breeds and shows dogs with her husband, Tony, with whom she owns a successful veterinary practice. After her visit to England, she and I kept up a fitful correspondence through our teens and early twenties, friendly but fundamentally misaligned letters. All her news turned on rugged outdoor activities and animal husbandry; mine was bookish and indoors-based, and then glib and in the city. You could almost hear the wrinkle of dismay that each of our letters provoked in the other. Even when Victoria married and had children, it amused my mother to note that most of her niece's communications favored the goings-on of the dogs and the horses. She thought her a fine, sensible girl. “I thoroughly approve of Victoria,” she said. There was no higher praise.

I look at my cousin as we drive through the northern suburbs on our way out of town. Her hair is shorter and darker than it was twelve years ago, and what I took then for shyness now manifests as a kind of no-nonsense economy. I think with panic about the present I have in my bag for her. Pink champagne is probably an even worse crime than white footwear.

“Is it fun being a vet?” I ask.

She is so stern and substantial, I wonder what of our history Victoria knows. I have never thought about this beforeâwhat, if anything, has been passed on by the six of my mother's siblings who have children. After all these years of avoidance and doubt, it is hard to believe there are people in the world who might have the same hang-ups I do.

I have had glancing contact with only one other cousin: Mike's son, Grant, for whom my mother had a soft spot. In the photos I have seen, he was the spitting image of his father, very South Africanâlooking, with a wide face and bumpy noseâattractive and grinning. When I was thirteen, I had found a strange letter from him addressed to my mother. It was stuffed in a folder in the kitchen with all the supermarket coupons and clothing catalogues. In large schoolboy handwriting, my cousin detailed how hard he had been practicing his cricket to get provincial colors, that he was learning the guitar, and that he had passed a home-economics exam in which he cooked sago pudding with meringue topping and an egg custard. I couldn't see why Grant had written to her, nor why she had kept it from me. Then, at the bottom of the letter: “Thank you Aunty Paula for sending me the Marlboro.”

I read this again and looked at the date; he was fifteen. My mother was buying cigarettes and sending them to my fifteen-year-old cousin, who was still at school. His mother had added a note at the bottom: “Paula you spoil that child, he was so excited to receive the cigsâno charges as it was 1kg. He has sold a few boxes to his friends.” If anyone had offered me a cigarette, she would have killed them and burned their body on the village green. If I had accepted and resold them at a profit, there would have been a playground massacre. It was like stumbling on evidence of a life prior to witness protection, where the rules were completely different. I put the letter back where I'd found it and didn't mention it when my mother got home from work.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

THE DOG PLACE

is in a field about an hour outside of town. My cousin gets out of the car, throws a whistle around her neck, and calls to order a group of dog owners milling in the sun. She begins to put them through their paces. “You should stay up here,” she says, turning to me and indicating the short, freshly mown grass of the children's play area. She gives me a mildly sarcastic look, then plunges down the hill after the dogs and their owners, forcing me to run with her as a matter of pride. The dogs yelp with delight as the owners thrash their way through the shimmering grassland.

It ends, thank God. We climb back to the top of the hill, where a small blond child runs over and throws her arms around my cousin. Her daughter is a cheerful eight-year-old who has been dropped off by another mother. I have watched Kirsty grow up in photos sent by my cousin, most of them taken at dog trials, with the little girl clutching a rosette for her winning dog or with her arms wrapped around the animal's head. Now she takes a leash from the back of the truck and snaps it expertly onto a young black Labrador. She is every bit as capable as her mother. The three of us get in the truck and start the drive home.

We had a lot of photos of Fay's three children in the house, two blond, one red-haired. My mother approved of redheaded children; it was an

Anne of Green Gables

thing, I think, and the fact that before her own hair darkened it had, she insisted, been on the red side of blond. In one of the photos, Fay's children were dressed in matching outfits. In another, the blond boy was holding out a banana to feed a monkey in their garden, which struck me at the time as impossibly glamorous. Fay's redhead was the sweetest-looking boy you ever saw, grinning in his school photo, and later, as a young man, standing haloed in sunlight. He grew up, got married, and had children, and when he was killed in a car crash when I was in my early teens, Fay rang my mother. I remember hovering in the hallway, alarmed by my mother's unnaturally quiet voice and the firm, soothing urgency of her tone. It was the parental voodoo that gets done in the face of a genuine emergency. When she got off the phone, she told me the news and, looking at me across a distance of several million miles, said brokenly, “Fay's baby is dead. She needed her mother.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

AFTER DRIVING FARTHER OUT,

we stop at a house set back from the road, surrounded on all sides by open country. I walk up the path behind my cousin. On the porch, a woman in brick-red culottes, with short brown hair and a white shirt is sitting in a garden chair. My cousin greets her and disappears through the front door. My aunt stands up, visibly shaking, and takes two steps toward me. We hug and separate. A second passes as we rake each other's face for the missing third party. “You don't look like Paula,” she says. She is half my mother's size, smaller, slighter, but otherwise similar. It is impossible to conflate her with the things I have read. We laugh nervously and go in.

My cousin is brisk and hospitable. She relieves me of the champagne and brings a tray of soft drinks into the lounge. Tony, her husband, is a large, attractive, affable man. He regards me with bemusement.

“So, your mom was Faith's sister?”

“Yes.”

“And”âhe looks at his wifeâ“you went to visit them in England?”

“Yes,” she says. “Twice.”

My cousin is apologetic. “I don't have much to do with the family,” she says, and it sounds like a coded directive to bugger off and find whatever it is I'm looking for elsewhere. The last time she saw any of her mother's siblings was when Doreen, our mothers' sister, visited five or so years earlier. Her hair was unkempt and streaming and she kept trying to pick up the toddler, who screamed. “I didn't like it,” says my cousin, frowning. “I didn't like it at all.”

Tony asks politely where I live. I tell him I have a flat in north London. This provokes a look of almost aggressive indifference. Most London flats, I add, are so small that when you throw a party in them it's like hanging out on a Tube train at rush hour. My cousin laughsâ“It sounds awful”âand we are suddenly on a friendlier footing.

Being a vet in these parts is not, I gather, a question of prescribing antidepressants to toy dogs or nursing pampered cats through cancer scares, but more one of keeping working animals maintained. From the way my cousin and her husband talk about it, it's a tough profession, more akin to farming. We go outside, and they give me a tour of the grounds. It is the first patch of earth I have seen that bears any resemblance to my mother's descriptions of this country: blazing sun on red soil; khaki foliage waving behind a heat haze in the distance.

There is a peacock wandering around, and dog pens for the breeding program. The children skitter on the grass, fearless around the family's animals, particularly the Great Dane, a huge, dopey-looking creature, jogging around the garden like a miniature horse. My cousin's youngest is a little boy with almond-shaped eyes and long, fibrous lashes who comes up to the dog's chin. “That child,” says my aunt, looking at her grandson in wonder. “That child.”

I have brought the blue-and-yellow Arsenal away strip for him, and he puts it on and runs around in the sunshine, squealing in delight. We spend the rest of the afternoon by the pool, watching the little girl do star jumps into the water.

As I leave, I pick her up and give her a hug. My cousin looks surprised. “She doesn't normally let people do that,” she says. We regard each other with friendly amusement and, I think, a certain amount of respect. “You can take your pink wine from the fridge. We won't drink it,” she says, but not unkindly. As she waves Fay and me off, I can guess what she's thinking: that whatever is going on between her mother and me, it's our business and she's glad to be out of it. I can't say I blame her.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

MY AUNT'S DEMEANOR

changes the second the car door slams. It is as if my cousin had been the adult, and in her absence, we become giddy as children. My aunt falls into a state of feverish reminiscence. “Your momâ” she says, and we're off.

We are driving to my aunt's neighborhood in the south of Johannesburg. It's a place I haven't heard of and can't even pronounce because, like a lot of Afrikaans, when pronounced correctly it sounds as if while saying it you are suppressing a powerful urge to vomit. It is early evening, the light a deep, burned yellow and the road almost empty. While she drives, my aunt tells me a story from my mother's first trip back here, in 1967. My mother went to the store to buy beer, and when she got back to Fay's house, recounted how every car on the road had beeped its horn and waved at her. “I'd forgotten how friendly South Africans are compared to the English,” she said, to which her sister, looking out the window, replied drily, “It might have something to do with the six-pack you left on your roof.”

“She told me that story, too!” I say. In my family-starved state, the sense of shared interest comes on like a head rush.

The house is at the end of a cul-de-sac, in a quiet suburb made up mostly of bungalows. It is almost dark by the time we get there. My aunt presses a button and the electronic gates open and close behind us. She parks the car under a carport alongside the house and we walk up the path. Through the gloom, I see a giant bird feeder on the lawn.

Fay was characterized by my mother as the sensible one. She is the one who holds down a job and owns her own home. She has sensible children. She talks in a low, even, sensible voice and doesn't get ruffled. Which isn't to say she'll be put upon. She is tenacious like all of them, and when she gets going on a grievance, she's like a dog with a bone. I have the same sense of her as one might of a celebrity, long talked about and unnerving, finally, to meet. At the same time, I feel instinctively protective toward her. Unthinkingly, I have absorbed my mother's position toward each of her siblings.

Fay shows me along a corridor to my room, where I dump my bags, and we return to the lounge. I sit on a sofa in front of what looks like my aunt's version of the Shrine: endless framed photos of her children and grandchildren on a sideboard where a TV might be expected to stand. She disappears into the kitchen and comes back with a three-liter carton of white wine and two glasses.

There was a glaring omission in my mother's paperwork: no letters from Fay. I don't recall seeing a single one. There were plenty from her sister Doreen, several from her brother Steven, even a couple from her brother Tony, but none from her favorite sister. Now, after Fay hands me a full glass and settles on the sofa, she pulls out some keepsakes, and there's a letter my mother sent in 1976. “The baby has all my faults,” I read, and I laugh. It's a backhanded compliment: my mother thought her faults a great deal more valuable than most people's virtues. Farther down in the letter she complains of being without family support: “I have no one to leave her with.” It was a refrain of my childhood, but I'm surprised to see it written here. There is no archness in the tone. Instead, there is something I never once heard in her: the ring of fresh vulnerability.

“She talked a lot about the wildlife, and weather,” I say. “And all the jokes you used to play on each other.”

My aunt starts giggling. “There was a maid called Flora.”

“Yes! I know about Flora!” I do not, as it turns out, know about Flora.

“She was mad,” says my aunt. “She'd climb that peach tree in the yard and sit up there knitting. Poor Tony at the bottom. Her husband had run off and left her.” There was another chapter to the Flora story that my mother failed to mention and which my aunt now relates. Flora's insanity extended to waking the younger children in the middle of the night and ordering them out into the yard to “harvest coffee beans”âacorns she'd buried in the dirt that afternoon. “We went back into the kitchen and she brewed them up and tried to make us drink them,” says my aunt, “before Mom woke up and took us back to bed.” She laughs. “Totally mad!”

Attracting staff who weren't mad was difficult, she says, what with there being no money and the tendency of her brothers to creep up behind them in the kitchen and drape a snake over their shoulders. Several already disturbed women had been dispatched, screaming, into the cornfields this way.

Fay digs around in the file of keepsakes and pulls out a photo to hand me. It's of a teenage girl in a uniform, leaning against a wall and looking cross.