She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me (23 page)

Read She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me Online

Authors: Emma Brockes

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Adult, #Biography

About a year later, there is a foiled robbery in the valley, in the course of which a tour guide is murdered. It is reported widely in the British press because Prince Charles had once stayed at his lodge. Pooly rings me in excitement. “Was that our man?” We try to remember. No. It was the other guy, the market leader.

The next morning, we take leave of the couple as if they're old friends, drive on to the coast for a few days, and then head home. On the road north, every highway exit signals the proximity of small towns and outposts with names instantly and intimately familiar to me: Eshowe, where my mother was baptized (by a Rev. Alwyn Whiteley of the Mission of Zululand. I imagine him in heavy black socks, looking out through the vicarage window, dreaming of Kent); Melmoth, where her parents lived at the time; Dannhauser, where she was a young child. I take the turnoff for Dundee, a mid-sized town where she was a teenager, and pull in at the high school. After turning off the engine, I sit looking dumbly through the window at the shrubbery in front of a redbrick building.

“One minute,” says Pooly, and hops out of the car. A moment later, she comes back.

“It was built in the 1980s,” says my friend. “Not one for us.” I have reached a point of exhaustion with all this. Either it will cohere at some point and turn out to have been useful, or be an odd thing I did once that was no use at all.

“We can try somewhere else?” says Pooly, gently.

“No,” I say. It is time to go home.

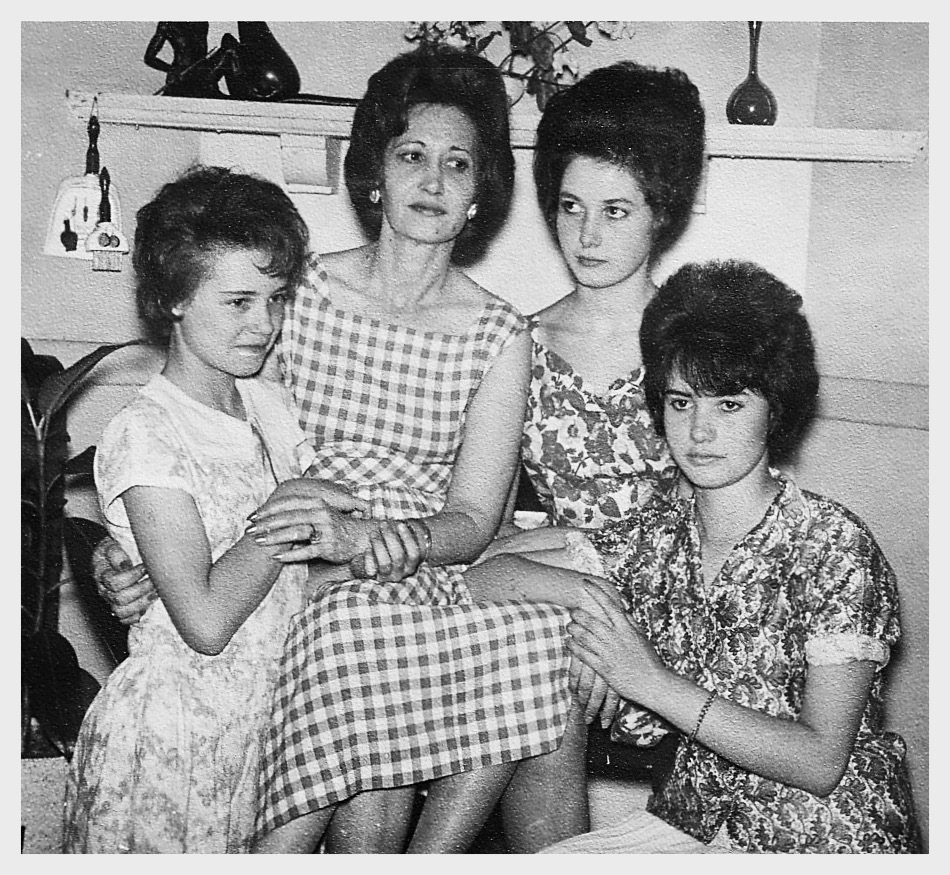

Family portrait: left to right, Barbara, my mother's youngest sister; her stepmother Marjorie, her sisters, Fay and Doreen.

Who Wears Hats to the Dentist?

THERE IS ONE LAST TRIP

I need to take: back to the coast to see my mother's sister Doreen. She is house-sitting for one of her son's neighbors in the village. This time we may be able to talk.

I am listless in the days before flying and after Pooly has left. The summer has gathered itself up for one final blast and the air is glutinous and distorting, the sound of the ice-cream van, with its sinister tinkle, muffled as it drives around the neighborhood. In the shade of the trees on Third Avenue two ladies in elegant robes and headdresses run a public telephone serviceâan ironing board with two old-fashioned telephones balanced on it, hooked up illegally via the junction box. When I pass them on my afternoon walks, they look like a mirage. One evening, there is a storm. I sit on the deck sipping tea and watching. It is just as my mother said: forked lightning like judgment; warm, quick snatches of wind; rain so hard it bounces off the ground and meets itself falling.

A few days before leaving, I take the car to the garage, and it stalls and dies at the end of the street, right in front of Siya. Lolling, graceful, he pushes himself upright from where he's sitting on the wall, and with a whistle summons men from the park to help out. He himself is far too grand to take part, but he organizes the effort with much barking and waving of arms. A large, sullen man has to be cajoled into taking the driver's seat, and he shoots me nervous glances throughout, as if I might call the police and accuse him of carjacking. When the engine starts, I give each of them ten rand, partly from gratitude, partly, I am aware, as some sort of insurance. Siya bows very low and gives me a glittering look, as if he has done me the favor, this fine morning, of allowing me to feel good about myself.

A few days later, I am walking down the street when peripherally I see a blurry movement: a figure crossing the park, jumping the fence, and traveling toward me at speed. My heart sinks; I am going to get mugged again. Ahead of me in the road stands Siya, and when he turns, I think, “A coordinated attack.” He grins broadly when he sees me, and then his focus shifts over my shoulder. The grin fades. Frowning, he lifts his hand and wags his finger, a small but unmistakable gesture: “No.” As I draw level with him, he grabs me by the arm and pushes me roughly up the street. “Go on,” he says. He sounds cross. “Be more careful.” I look back, and Siya is standing in the road, all boyishness gone, staring down a man who, half turned and muttering, is dragging himself up the street and back to the park.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

WITHOUT HER SON

as an audience, my aunt seems calmer, more thoughtful. After driving the three hours from George Airport, I pull up at the house, and she greets me with warmth. The house is more remote than Jason's, farther up the hill and on the edge of a semiwooded area, where a dirt track runs toward a logging facility. The lock on the front door doesn't strike me as adequate.

“Aren't you afraid up here, alone?” I ask.

My aunt shrugs. She has the blank indifference of someone inured to risk. “Not really. I'm lonely. I'm ashamed to admit it, but it's true.”

Doreen sits smoking on the terrace most days, looking out at the view. She is dog-sitting, too, for a poodle she has no respect for and refers to scornfully as a sheep on stilts. The owners have asked her to detick it every time she comes back from a walk, but “Fuck that,” says my aunt. “I'm not killing ticks for those people when they're not even paying me.” That afternoon, we take the dog for a walk and on the way back stop in for tea at one of the prettiest cottages in the community, occupied by an elderly couple who wouldn't look out of place in a village in Kent.

My aunt shows me off; a visitor from England, just the thing to get one over on these pretentious retirees with their fussy house and superior attitude and la-di-da anglicized accents. My aunt's belligerence in the face of perceived condescension is as familiar to me as my own face; it could be my mother sitting there. When David, the husband, shows us a photo of a large puff adder that materialized on their doorstep a month earlier and which he chased off, Doreen affects boredom. When he contradicts her assertion that if you take half a banknote into the bank, they are obliged to give you a new one, she becomes furious.

“Why are you disagreeing?” she says.

David looks surprised. “Because I don't agree.”

When we get back to the house, I laugh at her. “You got so aggressive with him!” I say, and Doreen looks mystified. “Did I? I didn't even notice.” Anyway, she says, she isn't sure about those two, with all their knickknacks and so pleased with themselves about the puff adder. “They're not my bag o' laundry.”

That evening, she cooks me stew, and as I put the glasses out on the table, she jokes, “Want to do a Ouija board?” She gives me a devilish look. “We could call up Jimmy.”

At last, over dinner, my aunt and I talk. Like Fay's recollections, Doreen's come out as sudden flashes surrounded by darkness. She guards her memories jealously in the face of her siblings' rival memories. When I tell her Fay has complete memory loss between the knife at her throat and the children's home afterward, Doreen snorts, “Really? Well, I don't believe that for an instant.”

When I mention Steven's decision not to marry in case he repeated the violent patterns of his father and brothers, she gives me an even more derisive look. “No one would have him, more like.” As Doreen talks, I think how everyone in the family congratulates themselves on being simultaneously the least damaged and the most afflicted of the siblings. The ones at the top had it worst, they say, because they had it longest. The ones at the bottom say they had it worst because, as well as everything else, they were bullied by the ones at the top. Doreen tells me about a fight she once had with Tony. She had brought her first boyfriend home, a well-spoken boy who, Tony sneered after he left, “speaks like a queer.”

“And you speak like a fucking Kaffir,” snapped his sister, and he hit her so hard across the face “I actually saw stars, like in a cartoon.” Being no slouch in this department, Doreen ran to the kitchen, picked up a bread knife, and, lunging at her brother, said, “I'm going to kill you,” before their mother ran in and managed to pull them apart.

I had never considered this; neither the pecking order of injury, nor the possibility that the siblings were anything but a united front against a common oppressor. A lively debate still rages, says Doreen, over who in a family that large can claim rights to middle-child issues. She smiles. “John thinks it's him, but I'm the real middle child.”

She looks at me curiously for a moment. “Why do you want to know all this?” she says. She knows I'm a journalist, and I haven't disguised the fact that I am taking notes for a book, nor that I have been to the archives to look at the transcript. But I don't think she means that. Doreen is shrewd enough to see through the camouflage.

“Because I won't be ashamed. Fuck that,” I say, playing once more to the idea we both have of my mother.

Doreen smiles. “Just like Paula.”

The first time my mother came back for a visit, Doreen was in her early twenties and with a failed marriage already behind her. My mother seemed a very glamorous figure, thirteen years her senior and with the worldly air of the returnee. She wanted to give Doreen the benefit of her experience in Swinging London and talked frankly to her younger sister about how to improve her sex life. I am as amazed by this as by anything I've heard. My mother, for all her posturing on how sophisticated she was, could not mention sex to me without chasing it up, a second later, with the suggestion that it would in all likelihood lead to death. When she ordered me clothes from mail-order catalogues, she invariably ordered them way too big. “Room to grow into,” she said. It was only years later, when I found photos from a holiday we took in my teens, that I saw with sudden clarity what I couldn't see then: a size-8 girl in a size-18 dress. If she felt the same kind of protective impulse toward her younger sisters, it was obviously outweighed by something else: a need to show off.

“Yes,” says Doreen. “She was quite helpful. Eye-opening. You know, you could try this, or this.” She looks at me wickedly while I make involuntary retching sounds.

We continue talking as we clear the table. “Fay was my baby, Steve was my baby” had always struck me as an odd choice of language for my mother to use. Were it not for her telling me about a small operation she had in her twenties, without which she could not have conceived, I would seriously have worried about the family tree.

“I think she told me about the operation for a reason,” I say, as we sit down for tea. “In case I found out about all this and ever started wondering.”

My aunt looks blank.

“You know,” I say, “is everyone related to each other in the proper way?” This seems to me such an obvious thought that I'm surprised by my aunt's shock. Doreen's jaw actually drops.

“My God,” she says. “You poor thing.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

THIS IS WHAT SHE REMEMBERS:

a gritty powder in the milk; a door opening in the night; a trip out into the country on a bicycle.

Jimmy brought them the milk before they went to sleep. Doreen noticed there was powder in it and told Fay to spit it out. She was only a child, but she had lived long enough in that household to assume it was some kind of sedative and fought to stay awake. A few hours later, her father crept into the room, and when she felt his hand go up her pajama leg, she kicked him so hard he slunk away.

She has almost no memory of the court proceedings. Doreen was a weak link in the prosecution because she hadn't been abused. There is an incident she remembers that she didn't tell the court. She tells me now. She was five years old. There was a green bicycle the children shared. Her father took her out into the country for a bike ride, and when they were sufficiently far from the house, dragged her off the bike and tried to rape her. “I screamed so loudly,” says Doreen. “Pure instinct. And I'm still screaming now.”

She remembers the children's home, the formal portrait of her father the staff made her put by her bed. The matron's husband was an Uncle Gussy, practically onomatopoeic for “child molester,” and sure enough, there was a scandal at the home. Fay had told me about this; that Uncle Gussy, who with his wife, Matron Flotto, left shortly afterwards, had been caught with his hand up one of the children's skirts. Fay told me she'd gone to her mother and said, “You did nothing last time. Now do something.” Marjorie removed them from the home the next day and they went back to live with her. Family life resumed.

“I didn't blame Paula for leaving,” says Doreen. “When my mother took the old man back, that was the end for her.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

MY AUNT WAS ELEVEN YEARS

old when she was called upon to testify in support of the evidence of her twelve-year-old sister, in whose name the action had been brought. Her sister and her mother had already testified. Waiting to go on was her sixteen-year-old brother, Tony, and her twenty-four-year-old half-sister, Pauline. This was the preliminary hearing, to determine whether the case would proceed to the High Court for a full trial.

The magistrates' court was in a small provincial mining town, fifteen miles west of Johannesburg and a few miles from the family home, although, the court recorded, the twelve-year-old was staying at the house of friends and her mother was staying in Johannesburg, at her stepdaughter's bedsit. It took place over two weeks in November, before a magistrate called Jooste. If my mother's contention was trueâthat the case foundered at the High Court because her stepmother changed her testimonyâthere is no record of it in the archive. The only records that remain, therefore, are those from the first trial, when by all accounts everyone was telling the truth. Any frustration I have at the missing paperwork is soothed by this fact.

And so here is Marjorie, who in this first court appearance holds her nerve, despite the extraordinary provocation of being cross-examined in open court by her own husband. She was thirty-seven years old. She had been married for twenty years. When I came to look at these papers again, I saw what I had not seen the first time. That this wretched woman, as my mother came to see her, had married him when she was only seventeen.

She confirmed her address to the courtâthat she was staying with her stepdaughter, Pauline, at Soper Roadâand the defendant stepped forward to begin his questioning. Only some of the transcript has survived, although enough to indicate his line of defense.

Q:

I have been drinking for about 20 years. Heavily for about 15 years.

A:

Correct.

Q:

You have known that I get blackouts whilst under the influence of liquor.

A:

Correct.

Q:

I had to ask you what had happened when I was drunk.

A:

Correct.

Q:

A few years ago we discovered that I was an alcoholic and I made desperate attempts to have it cured.

A:

That is correct.

She confirmed that at the time of their marriage her husband had a daughter from a previous marriage. She told the court she noticed nothing wrong at their first address, in Springfield, but at the second, at Zwartkoppies, in the district of Vereeniging, she became “a little suspicious.” One night, she heard her ten-year-old say the words “Leave me alone.” She went into the child's bedroom to discover the accused awake, the child half-asleep, and both covered by blankets. “I told the accused that the child should not sleep with him, she is too big.”

When the family moved to Witpoortjie, a mining community in the district of Roodepoort, the defendant worked shifts in the mines and would sometimes be home in the middle of the afternoon.