She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me (20 page)

Read She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me Online

Authors: Emma Brockes

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Adult, #Biography

“No, no,” I murmur. After a few more pink gins and the welcoming arm of the sofa I doze off. I wake up as Z is saying, “Tim's brother disappeared in Tongo. One rather assumes he was done in.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

THE COUNTRY IS PARCHED

and rocky around here, sparsely populated and tricky to cultivate. It's an area known for its large number of Scottish immigrants; the farms on three sides of the property where the murder took place were called Braemar, Clydesdale, and Abergeldy. Johan Hendrik Potgeiter, an Afrikaner in their midst, had called his farm KromellenboogâAfrikaans for Crooked Elbow, which described the shape of the stream that ran through it.

On Christmas Eve 1925, three men set out from Ladysmith, heading in the direction of the remote rural community. They traveled by motorbike, and if they had been trying to accrue witnesses as part of an elaborate hoax on the system, they couldn't have been seen by more people. A Madwendwe Kubeka saw them ride past his school in the direction of the farm. A Mr. Venter saw them standing beside the bike at the side of the road. They even stopped to ask a woman where they could find water. Her name was Ntombikazulu Mazibuku. She turned up among the state's forty-four witnesses.

The farmstead was at the end of a long track, concealed from the road. It had been reconnoitered in advance by the men, and Potgeiter, an elderly man, identified as an easy victim. During the course of the robbery, he was assaulted and died. The three men were seen by several people leaving the farm, heading in the direction of Brakwaal Station, where they abandoned the bike and boarded the train. Mr. du Plooy, the station foreman, remembered them clearly.

A few days later, they were arrested in Ladysmith, where they were found to be in possession of twenty-five one-pound notes, a pistol, some electric cord, and a set of silver hairbrushes. They had stolen a total of three hundred pounds from the old man and were charged with culpable homicide and robbery; they pleaded guilty to the latter.

At sentencing, Judge Tatham, while acknowledging that the victim's death was not their sole purpose, had no desire to be lenient. It was, he said, “an act of almost incredible meanness.” He referred to a similar case recently prosecuted in the Transvaal, for which two men had been sentenced to death. “Psychologists,” he said, in a modish reference for the time, “tell us that there is no power so strong as the power of suggestion.”

In his rather long-winded summation he wished to make a broader point. “In a population such as this,” he said,

consisting as it does largely of coloured people, white men who engage in transactions of this character must receive no more mercy than natives. They ought to know better. They ought to know the effect of their example. It is essential that the suggestion to commit a dreadful, cowardly and mean crime such as this should be accompanied by the suggestion that if it is committed, it will meet with the most severe punishment. It is impossible for me, having regard to the brutality of your conduct, having regard to its deliberation, and having regard to the importance of making an example of you to prevent others from committing a crime of this sort, to sentence you to a less term of imprisonment than that of 10 years with hard labor.

He had considered ordering them to be flogged as well, but decided against it, and so, on behalf of George V, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and of the British Dominions beyond the Seas, King, Defender of the Faith and Emperor of India, sentenced them to what was considered at the time a life sentence. There are, he said, “two classes of crime for which one is disinclined to show mercy. The first is offences against little children, who are unable to protect themselves, and the second is that of robbing old people, who are equally helpless.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

THE NEXT DAY IS SUNDAY.

Z, delighted to have guests, has invited a family from a neighboring property for lunch. The children, red-haired and freckled, flee outside and bound on the rocks like Irish setters. “Will they be all right?” I say. The youngest is about four. Their mother waves a hand; they are as familiar with this environment as the rocks themselves, she says. She has the air of a woman used to dominating a landscape.

“Now then,” says Z, pushing studs of garlic into a raw leg of lamb and turning to me. He wipes his hands on his apron. “What's all this about a murder?”

I go upstairs to retrieve the papers. The map accompanying the trial notes looks like a child's treasure hunt, with “Murder” written at the top in a round, slightly babyish hand, underlined and with a symbol to show where the body was found. I give a brief presentation of the facts.

“Who was the judge?” says the woman.

“Someone called Tatham.”

“Yes,” she says. “He was my great-uncle.”

From the kitchen a loud snort.

“Where did it happen?”

“A farm called Kromellenboog.”

“It's over there somewhere. Named for the shape of the creek; it's Afrikaans for âcrooked elbow,' you know. And who did he kill?”

“An old farmer called Potgeiter.”

She pauses for a moment and gives me a shrewd look. “His grandson still lives in the district.”

Z looks up with renewed interest. “Well, there's one for the local paper. Truth and reconciliation and all that. My grandfather killed your grandfather. Worth a photo at least! Come on, let's call him!”

My good humor evaporates.

“No,” I say.

Z has the diplomacy to drop it. When we leave, hours later, amid promises to meet up for drinks when Z's next in the city, Adam asks if I want to make a detour to the spot on the map. I hesitate.

“Come on,” he says. “We're right here. We might as well.”

It is harder to find than anticipated. The map is approximate and all the dirt tracks look the same. We pull off the highway and climb yet another unpaved road, cross a stream, and, on a slight rise set back from the path, pull up in front of a mean-looking farmhouse, surrounded by scrub. There is no signage, save for one discouraging trespassers. “Is this it? I think this is it.” We sit in the car and stare. Adam waits patiently, out of respect for whatever private moment I might be having. I'm not having anything. I feel ghoulish and silly. Whatever internal process these expeditions are serving, this place falls outside of it. I can just hear my mother's impatient response: “Stop looking for nonsense.”

“Come on,” I say. “There's nothing here. Let's go.”

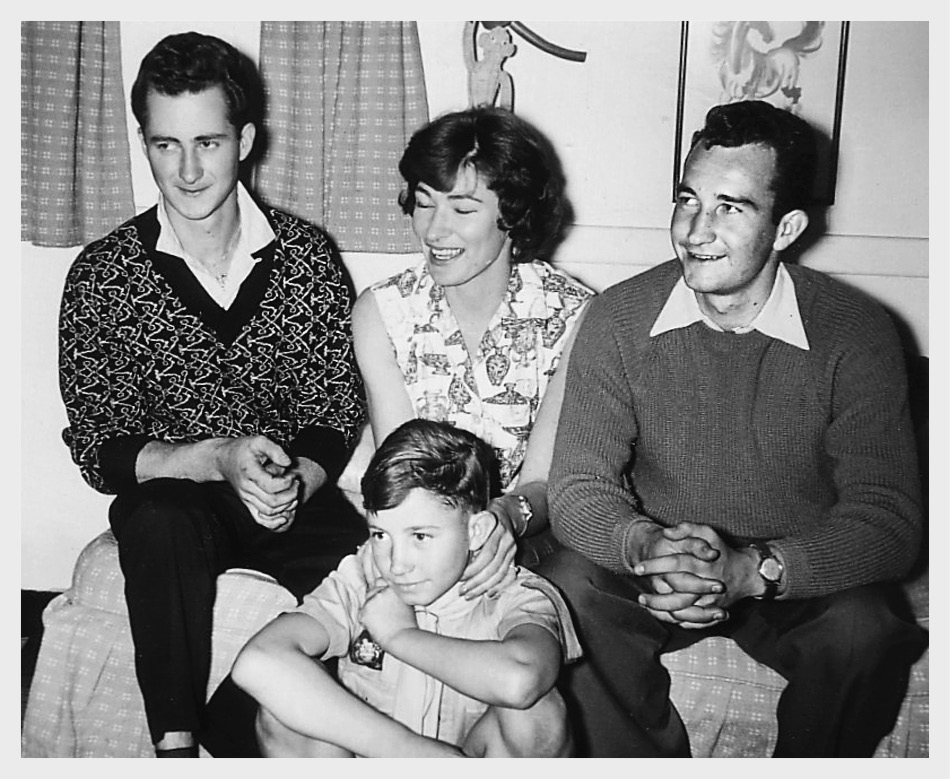

Mum and three of her four brothers: Tony, on the left, Michael on the right, and Steven on the floor.

Tony

YOU HAD TO WORK HARD

to get sympathy for being disadvantaged and white in South Africa, a country where 90 percent of the population was born into a disadvantage so intractably worse than yours that however bad your lot, you had only to look over the horizon to Soweto andâpoof!âthere went your alibi. To seriously contend, you had to be a fuckup of such unholy proportions that it attracted a kind of wolf whistle across the spectrum. “Jeez, man. Look at that guy. He's really going for it.”

My uncle Tony is living in a garage behind a shop in the east of Johannesburg. He is eight years my mother's junior. I remember his ex-wife, my aunt Liz, passing through England when I was young. She and my mother shut themselves in the kitchen, whereupon my dad and I, without conferring, instinctively posted ourselves to distant corners of the house, as far from the epicenter as possible, where in low tones some kind of country-and-western song was being performed, the it's-hard-to-be-a-woman back-and-forth centering on the terrible behavior of my mother's brother toward his wife and children. My mother threatened to kill fictional characters who beat up children on TV, and yet of her brother said only, “Shame, Tony.” To her, he was always the little boy she should have been kinder to.

It takes an hour to get there, after many wrong turns and reversals. I drive into an abandoned warehouse complex and do a U-turn fast enough for the gravel to fly. People I have drinks with every night boast of going to parties in the townships, but these parts of town are deprived in an unfashionable way and with unfashionable people. There are no automatic gates in front of the houses, nor signs threatening burglars with an armed response. Most of the properties are protected only by an ankle-high chain-link fence and the likelihood that anyone breaking in will be confronted by a drunk, angry white guy cradling an unlicensed shotgun.

Tony has instructed me to park in front of a corner shop called Sandy's and to go in and ask for him. It is the only business open in a row of boarded-up premises across the street from a boarded-up gas station, where a few gray figures of indeterminate race lie slumped against the wall. They look like lagged boilers with legs.

“You're here for Tony,” says the woman behind the counter, taking one look at me.

“Yes.”

She jerks her head. “Back out and around the corner.” I feel her eyes on the back of my head as I leave.

Behind the shop is a small concrete yard where a German shepherd strains on a leash, and next to it a garage with the door open. A man stands in the middle of the open doorway, surrounded by car engines and old batteries, tools hanging from the walls, oil-stained rags on the floor. He is wearing a white shirt and a gray suit. As he jackknifes forward to greet me, I recognize his face from the photos and in that moment realize why Fay can't be in a room with him. He looks just like his father.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

THIS LIVING ARRANGEMENT

is only temporary, says my uncle, while he sorts himself out. Sandy and her husband, Mike, let him stay here in return for light security duties: he keeps an eye on the shop. “I'm cheaper than the dog, eh?” says my uncle, and smiles. He pulls over a gas canister and urges me to sit. Then he jumps up and urges me to follow him on a tour of the garage. He shows me the cubbyhole off to one side where he sleeps, with a shower cubicle in the corner. There is a mattress on the floor, a potted plant on the windowsill, and some old school photos of his now grown-up sons are taped to the walls. One of them, my cousin Kevin, was killed in an accident while doing his national service. “You know Kevin died?” he says, pointing to a photo.

“Yes, I'm so sorry.”

My uncle rubs his forehead. Absent from the gallery is a photo Fay showed me, plucked from her box of memorabilia and handed to me slyly, without comment, like a test. It was a school photo of one of Tony's sons, ten or eleven years old, staring rather dolefully at the camera with a cut lip and the beginnings of a shiner. “Jesus, Fay,” I said. “Where were the authorities?” My aunt had looked at me as if to say, “Come, come. I think we both know better than that.”

My uncle pulls out a book from the pile on the windowsill and hands it to me. It is called

The Cure for HIV and AIDS

and is by someone called Hulda Regehr Clark, Ph.D. He has been studying her work, he explains.

“Have you heard of her?”

“Er. No.”

She's an American scientist, he says, who ran into trouble with the FDA and had to flee to Mexico. She was working on a medical invention, which Tony, using her research as a basis, has developed. He squats down and, rummaging in a box on the floor, pulls out a contraption to hand to me: two bits of copper piping attached by crocodile clip to a battery pack. You hold a length of piping in each hand, says my uncle, attach the battery to your waist, then switch it on for seven minutes and off for thirty. This influences something called the “human intestinal fluke.”

“Oh, right.”

“Everything has its own frequency,” says my uncle. “Even the human body.” He pauses. “You look just like Paula.”

We return to the garage, and I perch on the edge of the gas canister. Tony continues: “You get cancer from the alcohol in cosmetics and shampoo. The benzene goes straight to the thymus and the parasite breeds in there. This electrocutes them.” He holds up the piping.

“Did you meet Sandy in the shop?” he says.

“Yes. She seemed very nice.”

“Huh.” My uncle grins. “People call Sandy a suicide bomber because she walks around with this battery pack on. She had ovarian cancer, now she is OK. I wish I had known this in time for your mom. I fixed Mike's gall-bladder problem, too. It has a hundred percent success rate.”

“How many have people tried it?

“Sandy and Mike,” says Tony.

At that moment, one of the gray bundles from the gas station throws her head around the door.

“I need lend of ten rand,” she says.

“What for?” booms my uncle.

“Food.”

“You won't spend it on wine?”

She shakes her head. I gather this is a well-oiled routine. Tony fishes in his suit jacket and hands her a note. She shuffles out. “I'd like to beat her up and kick her butt,” sighs my uncle. “But the Lord said thou shalt provide for those who have not.”

He asks what I have been up to, and I tell him about my travels through the towns of his childhood. I tell him about stopping in De Deur outside the liquor store. My uncle grunts. “I remember that place. I hope you didn't go in. I bet the old man's tab is still outstanding.”

We can't hang out in the garage all afternoon, and since there are no cafés around here, my uncle suggests we get in my car and drive somewhere. “Do you object to casinos?” he says.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

MY UNCLE LEANS

out of the passenger-side window and hands over a card to the man in the tollbooth, who runs it through a scanner and hands it back to him. I gather he's been here before. Tony turns to look at me tenderly. “If I ever catch you in here, I'll beat you up,” he says. In the following order, I think: “If you do, you'll be talking to my lawyer.” Then, “I don't have a lawyer.” Then, “My dad's a lawyer!” Then (I'm not proud of this), “Thank fuck I'm middle class.” Finally, with astonishment, I think: “He was only trying to be nice.”

Like all casinos, there are no windows, no natural daylight, no clocks, nothing to pull the gamblers away from feeding their children's lunch money into the slot machines. It's not uncommon for men to shoot themselves in the parking lot after losing everything, says my uncle. We settle at a round chrome table at a café in a strip mall away from the main gaming room, where the ceiling is painted to look like the night sky and Celine Dion plays in the background.

There has been no formal request on my part for information, but the reason for my being here must be so nakedly apparent that Tony clears his throat and asks if I'm ready.

“Yes,” I say. I ask if it's OK to take notes, and he nods. I have wondered in advance about the state of Tony's memory. He is the oldest now, with potentially the oldest memories, but he is also the most hampered by addiction. His filters are burned out, and as such, I imagine, he is long past the point of trying to cover anything up. My uncle sits there, straight-backed at the table, and with the formality of a man bearing official witness, starts to talk.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

THEY WERE ALWAYS MOVING HOUSE,

says Tony. But the house he remembers best from his childhood is the one an hour south of Johannesburg, where my mother turned twenty-one; where they gave her the pajamas. There was no electricity, only candles. If they wanted to cook, they'd chop down a blue gum and throw it in the stove. They bathed in the water tank outside the house, first pushing aside dead birds and other debris. In lieu of running water, a man would come around with the water cart, pulled by a donkey, and they would buy forty-four gallons of water for two shillings and sixpence. My uncle has an extraordinary memory for numerical detail.

One day, they bought the donkey, too, for two shillings. “We had a little Box Brownie, and Ma put John on the back of the donkey and stood back to take a photo. When she looked through the viewfinder, he wasn't there. The donkey had died right under him, legs out. Two shillings down the drain.” He tuts at the waste.

For a while, Tony ran a thriving business catching snakes and selling them to other boys at school. They were rinkhalsâa type of spitting cobraâand he would grasp them around the throat, snap off their fangs with pliers, shove them down his shirt, and take them to school, where the teacher would say, “Anthony, sit still,” all morning. He was still bitter about the way things turned out. One day, he sold a snake to Brian Whitson for two shillings, and after taking it home, Brian let it escape through a hole in his baseboard. Brian's mother made them move house rather than live with the uncertainty of when and where it might resurface. “That damaged business,” sighs my uncle.

“We called Paula beanpole. Mike called her that. Throwing rotten tomatoes, that's family life, see.” His eyes ziz-zag, remembering. “We had a dog called Caesar. The police exhumed him and he'd been poisoned. We used to throw him scraps and he'd jump up, and the third time we'd throw him soap and down it'd go.”

His mother was always pregnant. With each new pregnancy, he says, his father would disappear into the bush, looking for herbs and leaves to terminate the pregnancy. “But they always hung on.” I see my mother's face shutting down as she says, “My stepmother was pregnant with twins, once.” I don't say anything. My uncle grinds on, eyes flicking this way and that as he scrolls through the past.

Boys slept on one mattress, girls on another. “A coir mattressâthat's like coconut stuffâbedbugs and no insecticides. Light from a tin with a wick in it; oil he brought from the mines. Foul-smelling stuff.” The toilet was a simple shaft, down a path outside. “You'd take a candle with you, and halfway there it would blow out and you'd scream.”

Every now and then a plague of fleas would sweep through the house, and the cat would be blamed. “One day, the old man grabbed our cat and dropped it down the long drop. Mom sent John and me to get it out. We took the ax and cut down a tree with a long branch. We lowered the branch down and the cat shot up it, scattering shit, and it never came back.” He chuckles. “John was covered in it.”

Their father was talented, he says. He could make anything with his hands. “When Paula turned twenty-one, Jimmy built her a cupboard with mirrors, and a light that came on when you opened it. It took him six months to build.”

He also fancied himself as an intellectual. My mother had said something about thisâthat her father always boasted of having started medical school at Wits, before dropping out. I had rung the admissions department, and after some persuading, they had gone away and looked him up but found nothing; although if he hadn't graduated, they said, one wouldn't expect to.

“He believed in all this metaphysics, mental telepathy,” says my uncle. “Every time he got drunk he'd get out these letters from doctors who'd thanked him for something or other. He would start his drink-sodden lectures with âThe basic fundamentals of life . . .' They went on and on. Big Jim liked an audience, he liked to lecture. And we weren't prepared to listen to that crap. That drink-sodden monologue. Mom tried to shut him up, and that's when war broke out. Then Mom would provoke him. We heard her screaming, âYou got fired?! And ten mouths to feed!' I thought, âFired? Did he get burned? Or shot?' But he lost his job because he drove the train into a donkey when he was pissed at the wheel.

“We thought he would kill her. She'd run like hell, and everyone would scatter. She was the slowest runner, so she'd climb out the window and I'd put myself in front of the old man so she had time to get away. He never ran farther than the front door. He was lazy, and it was cold and dark outside. Besides, once he'd chased us out, he had the house to himself.

“Big Jim would be standing at the front door, looking for who he wanted to kill. He's full of ink. He picked up this steel grate, once, which we had by the door, and threw it at me and Mom. We were crouching in the shadows. It went over our heads. It would've killed us. She would run to my roomâmy room was always the emergency escape, at the end of the house. She shot up the passage to my room. I'd see Mom fly past, then Faith, Doreen, Steven, Barbara, your mom, John, out of the window, over the barbed-wire fence, over the next fence into the veldt, and under a thorn tree. We'd wake with frost on the grass, shit between our toes. Faith was taking the grips out of Doreen's hair. Your mom got up and dusted herself off. âWe may be poor,' she said, âbut we sure see life.' âYes,' I said, âthat just about catches it. We've got a house but we sleep outside in the veldt!'” He laughs lustily.