She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me (21 page)

Read She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me Online

Authors: Emma Brockes

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Adult, #Biography

“He was a powerful man. They met in the passageway. I heard what I thought were blows landing, bang, bang, bang, five or six times. John said, âThat's a gun.' It was Paula's gun. I said, âSheesh, Paula has a gun?' Quite a woman. Next thing, he's standing paralyzed in the passage. She put two bullets in the wall, two in the ceiling, and there were two we couldn't account for. Knowing our dad, he would have taken a bullet and been too proud to say anything. He'd have slunk away and got it out with a penknife afterward. From then on, we said, âThe old man is carrying lead.'

“He had a sister, Nelly. She didn't disown us, but everyone else did. They said, âYou're Jimmy's boys,' and that was it. People have asked me about my dad. I say, âI didn't know him, I didn't see him, and when I did, he was drunk.'

“You go to school, you haven't got sandwiches. I stole raw potatoes and ate them. When you've been at that level, you understand many things. It's not the Russians, not the Communists. Your biggest enemy is your own family. You expect love, help. Instead, you find someone who wants to slit your throat.

“We would be woken at two in the morning by a hell of a racket. We'd look outside, and there'd be Mom with a spade and Paula with a torch, and the old man would be screaming at them to dig up his pots, but don't break them. If you don't find the drink, he'll kill you. If you do, he'll drink it and kill you. There were bottles of brandy in the cistern and under the hen. He'd send me to get them, and the hen would peck at me, thinking I wanted her eggs. You see what you miss?

“At the bus stop in the morning, the other kids would say, âWhy is your mom wearing dark glasses? Why is she wearing a jumper when it's eighty degrees?' You are embarrassed, ashamed. They would say, âJeez, man, what happened at your house last night? We heard screaming.' You are supposed to be proud of your mother and father, but I felt shame. My dad, fired first from one job then another. We never stayed in one place for long. He was run out of town. We changed schools so often.

“The railway ran by the house, and the old man would stop the train and spin the wheels for us. 'Round and 'round they'd go. He was drunk as a coot. There was a donkey man who came to clear rubbish from the house. At lunchtime, this man, with his mule and buckets, was crossing the railway line and the whistle blew for lunch at the mine. The mule wouldn't move. My dad ran straight over it. And he hit a car on the crossing, too. I don't know if they died. He was fired. My mom said, âIf you hadn't been drunk, you wouldn't have hit that car and been fired.' You see, you have these little pieces that you try to put together. âFired?' I thought that meant he'd been shot. âFired and ten mouths to feed.' The stress and the drinking.”

There were lighter moments. “One day, we said, âWhat's cooking, what's happening to Paula?' She'd painted on a beauty spot and wore lipstick and pink nylon. She walked back from the station when it was raining and there was a black streak down her face, and we fell about and said, âIs that beauty spot washable?'”

When Tony was sixteen, he got a job at the mines. It was against regulations to leave mid-shift. One day, the foreman fetched him and said there was an urgent phone call for him in the office. “It was Mom. She said, âCome quick, the old man's got a knife at Fay's throat.' We were afraid to call the police. He ruled us with too much fear.

“At the mines he drove the winding engine, which lifted and lowered the cage into the earth. One day, he invited us to go down into the mine. Paula took us, herded us all into the cage. We had little helmets on. The old man let the cage drop in free fall. Meters from the bottom he put the brake on. He thought it was funny. We thought we were going to die. We were so afraid. Paula led the way out.

“God put Paula there. She carried such a burden. Mom wouldn't have coped without her. Why I loved her? She didn't abandon us. She didn't desert us. Mike did that. I was fourteen, he was sixteen, and he went to Welkom, to the mines. He wasn't prepared to help. She endured hardship, poverty. At sixteen she earned her own money, she could have left. But she stayed. Without her help I don't know what would have happened. It's not long after that he had his knife at Fay's throat. The little ones, the little chicks, given to a home. After the trial he used to come to visit the children every two weeks. Paula said to my mom, âHow dare you let him back in?' That was the end for them.

“He wasn't all bad or always bad. He would do people a kindness. Thing is, when he made crap, he made really big crap. We needed a mediator, but there is only one mediator between God and man, and that is Jesus.”

A while after my mother's twenty-first birthday, her father got drunk, says my uncle, dragged the vanity unit he had made her into the yard, and destroyed it with an ax.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

I AM CROUCHED

over the table, scribbling in my notebook. My uncle's memories are coming so fast he can't control the order in which they come. When Tony was a teenager, he moved out and into lodgings offered by the woman who ran the local dry cleaner's. He started to date her daughter, Liz, and the two married. Liz's father was a tyrant, says Tony. My uncle wouldn't touch his own father, but “I put Liz's father in hospital twice in one afternoon. The ambulance hadn't left after dropping him off the first time when he said something about my mother, and I whacked him a second time. We went out and told the ambulance to take him back.

“You see . . .” He pauses. “Mike would beat me up, my own brother. We didn't go to hospital. The hurts were mental and emotional. Living in fear. There's no outward evidence of it. I would be dozing off and Miss Wells, in class, would hit me. I'd spent all night awake in the veldt, running with my brothers and sisters, sleeping in the foul hop, no books, no breakfast, no shoes, chicken shit between your feet and straw in your hair. And the teacher would hit me. She would use me as an example. If someone did something wrong in class, she'd say, âIf you're not careful, you'll become someone like Anthony.' I so wanted to tell someone. But the hurts were deep. You get people who write far-fetched crap; people don't believe things like that exist.

“I would have liked to have done many things in life. The foundation”âhe pushes his palms down, as if counteracting a strong upward forceâ“flattened. A child needs to sleep at night. We were despised, rejected. I was hated by my own family. That is why I love Jesus. Jesus says, âPick up your cross daily and follow me.'

“I drank like hell. They even gave me shock treatment. I was on Antabuse. They put you to sleep for four days, so you sleep through the DTs. I was seeing things. The doctor said, âYou're going to die.' It's like playing with a dangerous snake. Solomon must have been a drunkard, because he describes it so well in the Bible. I heard thousands of people screaming and raging.

“âBe still and know that I am God'âSeptember 1974. I read it in

Reader's Digest

. God lowered the boom. What a psychiatrist couldn't do, what shock therapy couldn't do, God got it in one. I went to the doctor and said, âBurn these appointment cards, I'm going!' He said, âYou don't know how sick you are. You can't cross a road without someone holding your hand.' But I was cured.”

“Mind over matter,” I mumble.

My uncle looks outraged. “No. You are robbing God of his glory.” He sighs. “Your mother was a difficult woman.”

I try again. “His mind over your matter.”

“Yes. That's it. Let me quote Jesus: âThe fear of God is the beginning of understanding.'”

He sighs again. “When James was away, everyone was happy. Paula and Mom would giggle like schoolgirls. Then he'd come back, and we'd be on tiptoe. He'd materialize one day in the bed; you never saw him come through the door.”

With cramp in my hand and the table edge digging into my chest, I feel an overwhelming need to say something bland and reassuring.

“But you've all done so well,” I say. “You're such good people.”

My uncle gives me a bald, hard look. “I'm basically quite a rotten person,” he says. “I'm violent and a drunkard.”

He sighs again and softens. “We grew up in a hell of a problem situation, but there was love. You can endure so muchâviolence, povertyâif there is love. Paula loved us.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

I HAVE BEEN IN THE CASINO

forever. I am never getting out. I have been here forever, I am never getting out, Celine Dion is never, ever going to stop singing. I excuse myself to go the bathroom. It is dim in there, the ceiling the same midnight blue with the sparkly motif. I put the lid down and sit. How strange to be in a casino toilet, absorbing this information. The weight of detail in my uncle's recollections is so crushing I can hardly breathe, but in the midst of my exhaustion I feel some measure of relief. Tony has corroborated that aspect of my mother's story I always found it hardest to believe: not that there was abuse, but that there was, in spite of it, such tenderness. I flex my cramped writing hand and go back to my uncle.

Tony has arrived at a point in his testimony that requires him to sit even more poker-straight, his eyes fixed forward. He clears his throat. With the severity of a painful and long-withheld duty that can, at last, be dispensed, he tells me that in the days of his recovery from alcoholism, he went to see a psychiatrist. The man put him on sodium valproate and made him talk about his childhood.

“Something terrible happened,” the psychiatrist suggested.

“Yes,” said my uncle. “My father raped my sister.”

He pauses in the retelling. “It took me twenty years to say it.”

What else is there to say? “Life is not a bed of roses,” says Tony.

It is dark when we leave the casino. We cross the car park and get in the car. As I start the engine, my uncle fishes in his suit jacket and pulls out a pamphlet entitled “God's Simple Plan of Salvation. A Matter of Life and Death.” He hands it to me, and I thank him. As we pull out of the parking lot, he sighs, and indicating the surroundings, says, “I have no money. Half of what I have I give to the Lord, the other half I give to the casino.”

As we fly down the highway at eighty miles per hour, I sense in my uncle some final agitation. It is easier, sometimes, to say difficult things in a dark car while driving; no one is required to make eye contact. My uncle clears his throat.

“Your mother was molested, too,” he says.

“I know, Tony.”

“Sorry. It's left here.”

I drop my uncle off and drive home.

When I get in, I sit on the porch, drinking tea for a while. Albert's light is a point in the darkness. I am moved by how seriously my uncle has taken this duty and by the fact that he has not tried to protect me with euphemisms. Above all, I am moved that it should have been Tony, the train wreck, the overlooked child, who has done this thing and spoken to me with such force and candor. My mother would be proud of him, I think.

Shouts drift over the wall from the men who live in the park. I think back over the stories my mother told me; of the jokes they used to play on each other, of the animals and weather. I think of how one reality can sit inside another, like a Russian doll.

The next morning, I ring Fay. I give her a précis of the afternoon. I describe the garage and the casino, the inventions and Jesus. At the end of the conversation there is a long, stunned silence. Finally, Fay says, “Tony has a

suit

?”

A few days later, my uncle rings. He has been thinking about it, he says, and there is something else he has remembered. When his father was in jail at Krugersdorp, awaiting trial, Tony went to visit him and took cigarettes. During the visit, Jimmy told him that he was sharing a cell with a corrupt lawyer who was giving him tips on how to defend himself.

“I thought it might help,” says my uncle, shyly.

“It does. Thanks so much, Tony. I'm really grateful.”

A father is a complicated thing. It isn't until many years later that it occurs to me to wonder what on earth he was doing visiting him in the first place.

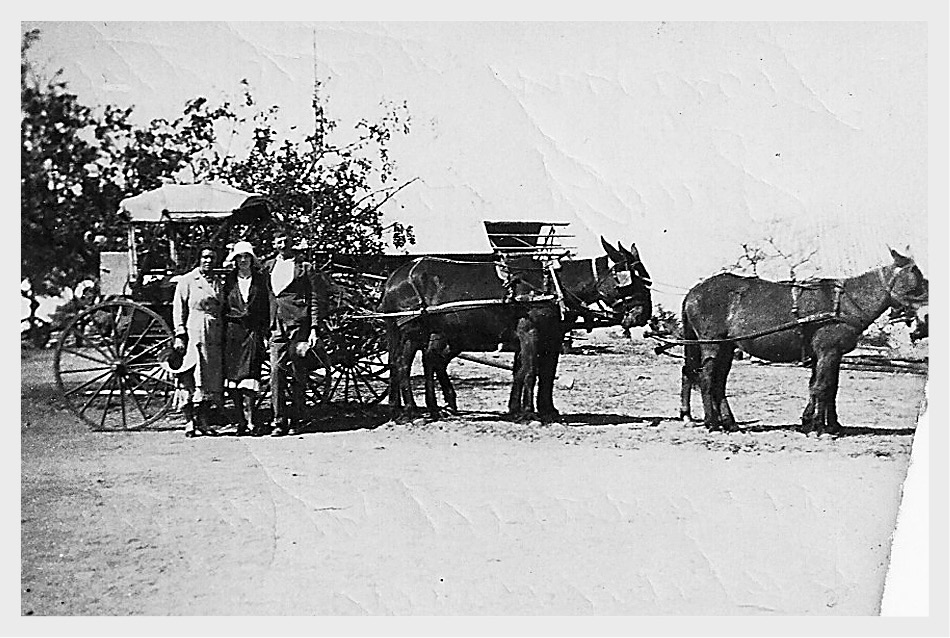

My grandmother on her wedding day, flanked by Johanna, her sister, and her brother-in-law, Charlie. My grandfather is behind the camera. They are on their way to the courthouse at Babanango.

Babanango

I GIVE UP THE PRETENSE

of doing any work. I take long, tepid afternoon baths. I walk aimlessly around the neighborhood, enjoying the bleaching effect of the heat and the light.

At night, I sit on the deck and drink tea. I read Antjie (pronounced “Ankie”) Krog's account of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings, in which those willing to confess publicly to crimes they had committed during the apartheid era were granted amnesty. As a gesture, it was powerful, optimistic. As a healing process, it was practical. Under the stewardship of Desmond Tutu, a new definition of justice evolved: truth as a form of punishment. No one could read those accounts dry-eyed, but Krog, a well-known Afrikaner journalist, cried so much that she had been jokingly referred to by other journalists during the hearings as “Pass the hankie, Antjie.”

For the first time, I have a dream of my family in which my mother is absent. It is just me and my dad, shopping on Oxford Street. That's the whole dream. We aren't trying to get somewhere to save her; I haven't put her somewhere and forgotten where. In the worst of these recovery dreams, my mother had been sitting in a hotel room, somewhere in a Dickensian-scape London, and while talking to her I'd had a sudden, horrific realization. “You're dead,” I said. “You're already dead and you don't even realize it.” She had looked at me so sadly. “Don't say that,” she said and I had run from the room, through a bunch of alleyways until I wound up in a pharmcy in Holborn. When I tried to find my way back to the hotel, the street had gone.

One morning, I shake off sleep, wash my hair, and put on a dress. The opportunity has arisen to do something everyone who goes to South Africa has a small, fluttering hope of doing: to be in a room with Nelson Mandela. It is a press conference at his charitable institute in the northern suburbs, convened to honor the life of his late friend the journalist Anthony Sampson. There has been a recent Mandela health scare, and most of the journalists in the air-conditioned room have spent the previous week scrambling to update their obituaries of the former president. As a result, the atmosphere is febrile and weepy, and when he walks into the room, stately on the arm of his personal assistant, every world-weary hack, every bombed-out old lag and war correspondent gets to his feet and applauds. People mop their eyes. Mr. Mandela sits down and, scanning the room, shows off his ability to summarize all human wisdom in a single utterance. “Good friends,” he says, smiling, “and doubtful friends.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

MY GOOD FRIEND

is coming to stay for two weeks, and I drive to the airport to meet her. I have a handmade sign to hold up at the arrivals lounge: “POOLY POOLY POOLY!” She rockets through customs dragging a pink hard-shell suitcase, whereupon much screaming: “Pooly Pooly Pooly!” Everyone turns to stare at us, the tall, skinny white woman and her shorter black friend. “Welcome back to the motherland,” I say.

“Oh God, they're doing my head in already. When I got off the plane, the man wouldn't stop going on about my afro.”

The plan is to do tourismâregular tourism, not the twisted tourism I have been doing. We are going to look at places where great historical events occurred and drive to areas of natural beauty and feel uplifted by things that are bigger than we are. Since Pooly spent her teens and early twenties demonstrating against apartheid outside Manchester Town Hall with a Socialist Worker placard, this should be fun.

Back at the house, she unpacks the care package she has brought me from home: a packet of cheese puffs, a packet of wasabi peas, a Fry's chocolate cream bar, and a cutting from the

Evening Standard

about a man we both hate being named one of Britain's thirty most brilliant people under thirty. We scream and repair to the Mozambican bar on the corner, where the barman sends over free drinks; mixed-race parties, even British ones, look good for business in this modish part of town.

The next day, we go on a bus tour of Soweto and take photos of each other giving the thumbs-up outside Nelson Mandela's old house, specifically his trash bins, which to our delight still have “MANDELA” daubed across them. We drive to the outskirts of town to the Apartheid Museum, a stark, brilliantly designed building reminiscent of the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin. At the entrance each visitor is given a ticket categorizing them as white or black, and they are made to enter the building through different doors, a gimmick that, while we giggle on drawing tickets that invert our races, has the effect of being kicked in the mouth. It is only four p.m. when we leave, but we drive straight to the bar and don't leave until the early hours, so slammed on banana liqueur that I wake up the next morning horrified that I drove two blocks home. In the garage, the car is parked at an angle and the side mirror is cracked from my drunken reversing. We tell ourselves it was a necessity, that walking home in that state would have been more dangerous than driving, but the shameful truth of it is, there is simply less of a taboo about rule-breaking here. You might get murdered but you almost certainly won't get a parking ticket.

The day before we leave for a road trip to the south, we go for lunch with my two aunts Fay and Liz, Tony's ex-wife. I have seen her once since arriving in South Africa, for lunch at Fay's house. She had brought a date, an Afrikaner who looked like a cross between W. H. Auden and Plug from the Bash Street Kids. Fay and I joked afterward that he could lend his face to a fantasy clothing label we came up with called Hill-Billy, Inc. Liz has amused, cobalt-blue eyes, bright blond hair, and a breadth of shoulder that could knock down a door. I think she is superb.

We are having lunch at a country club in the east of the city, where Liz lives not far from her ex-husband's garage. I pick up Fay on the way. British people think themselves worldly on the subject of alcohol, journalists in particular, but today we are out of our league. It is a nice restaurant and we eat outside on the terrace, overlooking the lawn, but halfway through the meal there is a sense of eagerness from the two aunts to get back home and down to the real business of drinking. After a few gin and tonics, Liz starts to address Pooly as “mamma,” an endearment white South Africans use for their staff that makes us both giggle into our drinks.

After lunch, we get in my car and drive to Liz's house. My aunt asks me to pull in at a liquor store, one of those depressed-looking outfits with a grille over the window that open on the corners of rough estates. I buy bright pink wine, the most festive, nonindustrial-looking bottle they have, and we proceed to the house, a bungalow with a pretty garden out front. When we walk in, a man stands silhouetted in the dimly lit corridor. Liz introduces him as Johannes, her boyfriend. He takes one look at the group, steps back without speaking, and retreats down the hall. A door slams. Liz rolls her eyes, says something disparaging, and exchanges looks with Fay. As we adjourn to the living room, the first bottle disappears almost before we sit down, and with Johannes locked in his room, as we imagine it, loading his gun, Pooly and I exchange looks of our own, hug the aunts, and leaving them to it, return to the car.

“Hey, mamma,” I say, “which way?”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

BECAUSE I CANNOT LET IT GO,

we have devised a road trip that runs through one of the country's main tourist attractionsâthe Zulu battlefields at Isandlwana, which also happens to be near Babanango, the place where my grandparents were married. Sentimentally, I think, “It is where they were happy,” although I have no evidence for this. It is merely where they were young and, in at least one photo, smiling. I will settle for that. Babanango is a rural outpost some three hundred miles southeast of Johannesburg, the name of which, I discover, comes from the Zulu, “Ubaba, nango” meaning, “Father, there she is.” It refers to the myth of a child who was lost, at the joyful moment of recovery.

I haven't given much thought to the route beyond trying to memorize the quickest way there. It hasn't occurred to me, for example, to note how after leaving the highway the roads become minor, and then less than minor, petering out on the map into faint spidery lines in oceans of white. After a few hours on the road, Johannesburg's talk radio bleeds into Afrikaans Bible rock and then slowly dissolves into static. It gets noticeably hotter. The sky is lightning white. The road runs between fields of sugarcane, too high to see over. Eventually, our cell phones, balanced in the cup holders, peter out too, and it is here, at this place so entirely beyond the reach of help, that I decide to tempt the universe.

“It'd be funny if we broke down,” I say.

A few minutes later, we pass a giant lizard in the road. It is huge, with a punklike crest, giant scaly haunches, and slow-swiveling black eyes, lumbering across the road with the indifference of a bad waiter. “Stop the car!” screams Pooly. I pull over, and she jumps out.

“Come and look!” she says, crouching over it.

“I can see it from here. It's disgusting.”

I sit in the car with the window down, listening to the white noise of a thousand smaller noises: the clicks and shakes and chirrups from the cane fields.

Pooly returns to the car, looking at the screen of her digital camera. The lizard continues to sit placidly at the side of the road.

“Freakin' Godzilla.”

I turn the key in the engine. It makes a sound like gravel being shaken in a tin. I do it again. And again.

“Stop it.”

“I'm not joking.”

“Stop it.”

“I swear to you.”

We sit for a moment in silence. We look at our phones. We try to remember how far back it was the radio signal died. Eddies of dust. A flash of being in the car overnight and the things that live in the fields crawling out in the dark to seek the cool, flat surface of the road and, perhaps, the car.

When we first hear it, it comes as a layer of noise on top of the crickets, like a distant lawn mower, building steadily. “What's that?”

Pooly gives a small, incredulous laugh. “You know what it sounds like?”

I look at her.

“Motorbikes.” The only thing less preferable to being out here alone.

Within seconds it is like a scene from

Mad Max

. Bikes start to fly by, with that glottal-stop key change as each one passes the car, a slam of noise and air. The lizard's tail is still jutting out slightly into the road.

No one stops, and the high climb to panic just as swiftly drops to a rush of relief. We would have only the mild discomfort of a hot wait for a regular car to pass. I am flooded with such hysterical optimism that I say, “In any case, bikers often have hearts of goldâwhat's that Cher film with the deformed son, and they're all bikers?”

“

Moonstruck

,” says Pooly.

“No, the other oneâ”

A tonal variation makes us turn; two bikes have slowed down and are pulling up between us and the lizard.

My elbow is hanging out the window, and I instinctively pull it in. The two men are large, hairy, and in full leathers, with black shades and bandanas around their heads. One starts to get off his bike, and as he turns, prominent on the arm of his jacket are two patches: one is a swastika; the other is the apartheid-era South African flag.

“They can't do anything to us,” I say quickly. “We're British citizens. It would cause a diplomatic incident.”

Pooly has less faith in the state than I do and scoffs. South Africa doesn't give a stuff what Britain thinks of it, she says, and vice versa. Something stirs in the depths of my brain. “You're wrong,” I say. “It has strategic importance within the region.”

I throw my head out the window, and operating on the principle that people will rise or descend to the expectations you have of them, put on a simpering English voice that I hope implies confidence in this man's mechanical skills and his general politeness to women in distress, but which I realize afterward is the same moronic tone I used on Mervyn in the bookshop.

“HELLO!”

The man holds up a black-gloved hand to silence me. He turns his back and starts to walk away from the car, while the other guy dismounts.

“What theâ?”

The first biker crouches down over the reptile and, gripping it under its throat and tail, heaves it up into his arms and starts to walk toward the scrubby edge of the cane field. This is menacing in a way I can't describe. Looking back, the obvious interpretation is that he was doing the creature a service, but to us it does not look like that. It looks like he is removing the only witness. That he has touched the lizard at all seems to break a powerful taboo, his kindness to a reptile indicative of his cold-bloodedness to humans.

“Oh, God.”

The other man approaches my open window. He has a patch on his jacket, too. It reads, “Can I see the front of your bottom?” Pooly's elbow is so far into my rib cage at this point I can hardly keep the mad smile on my face. She gives the biker a little wave, waggling her fingers in a cooee-type motion as if spotting him over the garden fence.

“Hello!” I say. “We're from England. I can't get the car to start.”

The man's eyes flick from one to the other of us. I am wearing a pink, Jackie Oâstyle 1960s dress over jeans, with white sneakers. Pooly's afro is scraping the interior of the car's roof. The man turns to his friend and, shouting something in Afrikaans, they both stare at us for a moment. Finally, in a clotted voice, as if English is barbed wire in his mouth, he says, “Is it a hire car?” The smile on my face is so broad it is hurting.

“Sort of. I'm hiring it from a friend.” This seems to displease him.

“Something's burning,” he says. He makes an impatient motion for me to open the hood, and then he and his friend disappear out of view. A few moments pass.

“Fascists under our bonnet,” I say to Pooly.