She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me (17 page)

Read She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me Online

Authors: Emma Brockes

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Adult, #Biography

We have forty minutes to kill, so we go into a diner by the bus bay. The waitress looks strained as she serves us, and by the time she brings out our food there are tears flowing down her cheeks. My uncle asks what's wrong, and with weird honesty she says her brother was found hanged that morning.

“I can't believe she came into work,” I say uselessly. When we leave, he gives her a big tip.

There is something my uncle would have liked to have shown me: a box of papers that were in his car which was recently stolen. It was memorabilia that included a lot of his father's line drawings and poems. They were very fine, he says, and I wish in that moment I could see them, too. Then, on the bus to Cape Town, I wonder why. Does it make my grandfather less monstrous that he drew a nice picture or was “sensitive” to poetry?

We drive along the Garden Route through dusty Dutch towns and neon-green valleys. I think of my mother getting up from her chair and saying blithely every time, “I will arise and go now / And go to Innisfree.” She always quoted that line from Yeats. “Nine bean rows will I have there, a hive for the honey bee / And live alone in the bee-loud glade.” She was so tone-deaf she even quoted poetry flat, and I would howl at her for killing it. We had the poem at her funeral. I think about it now in relation to her brother. She would be happy, I think, that Steven had found some kind of peace here, if that's what it was, sitting and smoking and looking out from the stoop. Then I think of the waitress at the diner, tears flowing down her cheeks. This fucking country.

I have another letter from Steven. He sent it to my mother after I left home, but before she was ill. She rang to tell me about it and, not having the patience to wait for me to come home, read it to me over the phone, her voice rising and falling with the same flat cadences she used to recite poetry. It was the only time, apart from after Mike's death, I heard her fighting to keep back tears.

My Beloved Sister, in a couple of months I will be a qualified psychotherapist and will set up my own practice next yearâI have had a couple of dramatic years pioneering wilderness therapy and working with severely disturbed young people from the Katlehong township and squatter camps. All this is not to boast over my unexpected glory but to let you know that I have not been malingering here in Africa! In some strange alchemical fashion I have managed to wrestle something valuable out of my existenceâI was discussing it recently with my therapy supervisor and she asked me how I accounted for it. Without hesitating I responded that it came from the magic of being a child at your beloved feet my sister. The therapist informed me that I had an obligation to let you know itâit isn't an obligation, but a supreme joy to thank you for those little veins of gold that finally wove their way into everything sacred in my lifeâSteven.

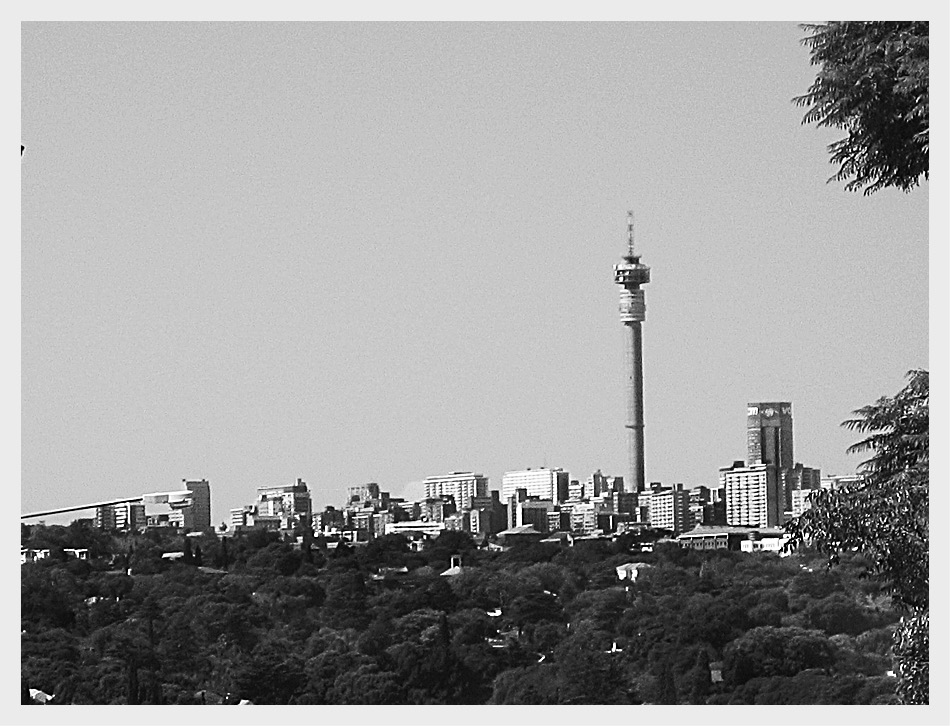

“Better than Manhattan's”: the Johannesburg skyline.

Eloff Street on a Saturday Morning

“WHAT DOES SHE DO ALL

day up there?” says Fay on the phone when I get back to Johannesburg.

“Smokes,” I say. “Looks out of the window. She seems happy enough.”

“She thinks the world owes her a living. And Jason?”

“I liked him.”

“He charmed you.”

“Doreen thinks his girlfriend is a Satanist.”

“I feel sorry for her,” says Fay.

“I feel sorry for her,” says Doreen airily, when I ring her to say I got home safely and have spoken to Fay. “And Steven?”

“I liked him.”

“You were taken in by his bullshit,” says Doreen.

“I'll come back next time for longer.”

“Yes. Well.” She is suddenly distant. “I must be going now. Give my regards to your father.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

MY DAD HAS FOUND

a buyer for the house, and I am going back to help with the last of the packing. After he picks me up from the airport, we drive through the suburbs of west London, and all the things I might tell him seem absurd to the point of embarrassing. I had a good flight, and by the way, did Mum ever mention to you she shot her dad?

These stories don't travel. Over the phone, I had told my dad some of what I had seen and heard, and he had said lots of sensible things that reassured me immensely. Being able to talk to him like this only emphasized the extraordinary nature of my mother's self-sufficiency: no parental safe harbor, and all the experiences I found painful just hearing about were hers firsthand.

Still, there are limits to what can be said when you are accustomed to not saying things; when saying things has always been construed as a weakness.

“How is it going?” says my dad as we drive from the airport. London seems small and gray and wonderfully familiar.

“Cor, they're a pretty wacky bunch,” I say, and I laugh.

I am glad to be home, although it is not quite home anymore. Something has happened to the house. While my mother was alive, it had looked like a complicated but more or less explicable systemânot the crazy-person hoarding of newspapers. There was an architecture to it all, invisible to the naked eye, which with noblesse oblige my dad had been permitted to slot into for thirty years. Now everything looked bizarreâfragments of a civilization once infused with importance whose meaning had, somewhere along the line, become obscure.

My dad and I move through each room, trash bags in hand. By the door in the kitchen, an entire closet filled from floor to ceiling with plastic bags. In the drawer beneath the sink, hundreds of rubber bands she picked up in the street where the postman had dropped them. In the cabinets, endless margarine tubs, washed and neatly stacked forâwhat? A container crisis that never came?

My mother would have been brilliant in the Second World War or in Mao's Great Leap Forward. She could've fulfilled scrap quotas for entire villages. Long before it was fashionable, she took up recycling and had a waste disposal system in place that would, typically, find her fishing through the garbage to pull out a pear core, wrongly deposited by my father or me, and which she would hold aloft between thumb and forefinger to cry, “Are you

trying

to starve my birds?” (Vegetable matter went under the feeder, to supplement the seed ration.)

“Don't interfere with my system!” she said, if you had the temerity to suggest throwing something away. The Smarties lids or ice-cream tubs; the iron-on patches and old bottles of sun cream. Shoe horns, hair clips, unidentified gray liquid. Scarlet food coloring. Handy-pack wafers. A lifetime's supply of used envelopes. In a drinks cabinet in the living room we found a disturbing mandarin suspended in syrup like a fetus. Pipe cleaners; packets of sugar from Iberia, the national airline of Spain. Beads in a tin. Fucidin H cream “for external use only,” insect repellent, Algipan balm. Dental sticks, shower caps, cork mats, belts belts belts. An army sewing kit. A tiny bib, liberated from a pair of child's dungarees; cat collars, double-sided sticky pads, loose pajama cords. Empty boxes of mint thins, still breathing the ghostly air of peppermint. Sacks of birdseed; something called bloodworms for the fish.

“Why are you writing it down?” says my dad, and I can't say. It looks like a life's work. He has been struggling alone with it for weeks and is at the slash-and-burn stage, but I am still dithering over every last item. My front pockets are stuffed with name tags she used to sew into my PE kit, even though she hated sewing. In my back pocket is a horrible porcelain magnet in the shape of a cat that my mother bought at a Christmas fair and stuck to the inside metal frame of the window in the kitchen. These things will end up in a storage unit in London, and for years I will pay through the nose to keep them there, in misguided observance of my mother's core principle: that there is nothing in life that can't be made use of.

In the kitchen, I reach up to a drawer above the stove and heave out a glass jar of desiccated coconut. My dad smiles. It would be taken out twice yearly when my mother made curry, hefted onto the table with a groan and her favorite catchphrase: “You could kill someone with that.” (People notwithstanding, she approved of things that exceeded their proper proportions.)

“How old is that stuff?” I would say.

“Old enough to be your mother.”

“I'm not eating it.”

“Nonsense.” From the back of the cupboard, papadums, which she transferred to the plate with a magician's sleight of hand.

“Let me see the packet.”

“Sit down.”

“I'm not eating till I see the packet.”

“For goodness' sake.”

“Excuse me”âthis was the era when all my sentences began with “excuse me”â“best-before dates do exist for a reason, you know.”

“There's nothing wrong with it,” said my mother. When she said “There's nothing wrong with it” before you'd even started eating, you knew you were in trouble. I made a dash for the cupboard.

“You're going to get such a slap in a minute.”

Next to a box of ice-cream wafers with an outdated typeface, the papadum packet. “For God's sake. Best before April 1976.” Something like thatâI remember they predated our move to the house. She smiled in triumph.

“You wouldn't last five minutes in Africa.”

I hold it aloft, my dad opens the trash bag.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

MOST OF THE EMOTION

generated by seeing the house go is used up by the sheer hard labor of dismantling it, hauling sacks of refuse into the car and out again at the municipal dump. We drive back and forth three times a day. For some reason, the more trivial the item, the harder it is to part with. The margarine tubs look particularly pitiful at the bottom of the dumpster. Discarding them feels like an assault on her dignity. After the last of it, the removal vans come to take what's left into storage, and with an overloaded car we drive into London. My dad is staying with a friend until the paperwork on his new house is finalized. After almost thirty years away, he is moving back to west London, where he and my mother started out together.

I see some of my friends in those weeks I am back. To those who ask, I talk about the trip in general terms. I talk about the weather and the price of the sushi. There are certain people I instinctively avoid, those who after my mother's death wanted nothing more than to stroke my arm and console me; who urged me to call them whenever, even in the middle of the night. (I am not against this offer per se, only when it's used by those whose need to be confided in outweighs all other considerations.)

“I feel like I'm not hearing something?” says an intuitive friend at lunch, after I have fobbed him off with trivia about my trip. I hesitate. I don't want to embarrass him. The story makes too great a demand on the listener. I can't stand it, the look of embarrassment and panic on a person's face as they cast around for an appropriate response. Suddenly, I understand my mother's glibness, her insane giggle when she said, “I thought I might have to shoot my father.” What

is

the right tone for that kind of statement?

With a lurch, I realize how afraid she must have been, that these things in her past would put her beyond reach of common understanding; that they would make her alien, even to me. I give a brief outline, and although he responds with measured incredulity, is sympathetic without being prurient or arm-stroking, afterward I'm convinced it was cover for his real response: gut revulsionâtoward my family and me for what happened in the first place, and toward me exclusively for the vulgarity of passing it on.

Something happens around then that, although I'm not willing to see it, drives home just how gripped I still am by my mother's orthodoxies. I interview for my newspaper an eminent movie star who, during the course of the interview, unexpectedly tells me that later in life she discovered that her mother, who had killed herself decades earlier, had been sexually abused as a child. “They say you inherit the guilt,” said the actor, “but what you really inherit is the silence.” I am so horrified that instead of following it up, I panic and change the subject. Although this aspect of her background hasn't been reported on before, I do not include the line in the piece.

On a rainy March evening, my dad drives me once again to the airport. After the odd, transitory weeks in London, I find I am excited to be going back, to have something known to go back to. Now I have an outline of the story, I want to color it in.

“Be careful,” says my dad.

“I will.”

“If you want me to come out there, you'll let me know.”

“I will.”

“Mum wouldn't want this to take over your life.”

“It isn't. Honestly.”

“Bye, baby.”

“Bye.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

IT IS DIFFERENT THIS TIME.

I land in bright sunshine. Instead of going to a hotel, a car takes me to a house in a street of other houses, with a sidewalk you can walk down to a strip of bars and restaurants. Until I find somewhere more permanent to live, I am staying in a guesthouse, known to me through the informal network of journalists that in my previously dingy state I hadn't felt fit to exploit. (Journalists will, generally speaking, help one another out, if it doesn't compromise their own interests too much and if the help can be administered over drinks in the bar.)

The first night back, there is a drinks party in the garden of the guesthouse. In the balmy twilight air, I sit and drink white wine and feel my shoulders relax. The company is familiar, reassuring, and fairly representative of the neighborhood: two Australian medics on their electives; two British journalists who live in Johannesburg and drop in every night for a drink; and an American called Alan, who holds out his hand to introduce himself.

“I work in disaster relief,” he says. One of the journalists catches my eye and swiftly drops it. “That's my day job. But really I'm an unfunctioning artist. Notice how I say unfunctioning, not dysfunctional.” He raises his eyebrows, and I must look blank because he gives a small laugh and says, “Don't make the mistake of taking me seriously. I have a certain humor not everybody gets.”

Alan is staying in the guesthouse, too. The night before, he says, he went to the bathroom in the middle of the night and, yanking what he thought was the cord for the light switch, summoned armed response to the door. It is the second time he has done this in a week. I ask what he is in Johannesburg for, and he says he is here on his own time, to investigate the “frontiers of postracist society.”

The Australians stare.

“Yes,” says Alan. “When I lived in San Francisco, I got up in PR disguise sometimes, to see what it was like. You know, to be targeted by racists.”

“Why would racists target you for being in public relations?” asks one of the journalists politely.

Alan closes his eyes. “PR as in Puerto Rican,” he says. “Another oppressed people.”

In the days that follow, I do all the things I didn't do last time, things that will ground me, I think, as I travel deeper into my mother's history. I buy a local cell phone. I figure out where to buy groceries. I walk around the neighborhood, the sun on my back like a hand, pushing. Away to the right, the city stretches off beneath a canopy of trees, gathering like a well-tailored skirt at the skyline. Better than Manhattan's, I think.

Up the hill, past the bead shop, past the newspaper shop selling weird vegetables in a box by the door, under the covered walkway, where hawkers sell beaded wire animals and other knickknacks laid out on bright fabric. In the street, men in neon vests mill about, keeping an eye on the cars. They are paid by local businesses to deter thieves, but after a couple of days of waving madly at them each time I pass, I suspect their deeper purpose is to relieve Western visitors of an urgent need to be nice to a black South African. One of them, Joseph, spends most of the day asleep under a newspaper on a derelict porch, knocked out by the sheer force of foreign goodwill.

A man standing in front of the secondhand-book shop sees me coming and retreats, slightly, into the shade of the doorway. I had gone there on my first morning, and after buying an ancient, liver-spotted copy of Rilkeâ“Lord, it is time / The summer was so great”âheld out my hand across the counter.

“Hello!” I said. The man was white, with thick milk-bottle glasses and a lime-green shirt. He took the full force of all the pent-up condescension left over from my exchange with the car guards. Reluctantly, he shook my hand and introduced himself as Mervyn. Mervyn, I decided, was quirky and fun.

Past the sushi restaurant, the gallery with the piece of driftwood arranged artfully in the window, the brunch place that serves two types of tapenade. At the end of the street is a shopping mall, laid out in a horseshoe around a car park. There is a telecom provider, a supermarket, a travel agent, and a place on the corner where chickens turn, bumper to bumper, on a slowly revolving spit. The whole complex could be in a regional English town were it not for the foliageâarmy-surplus brownâand the heat, rising from the parked cars in broad, muscular waves. Walking through it is like pushing your face into a substance that, for a split second, continues to hold its impression.