Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (3 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

As a writer and mother myself, I am struck by how contemporary Jackson’s dilemmas feel: her devotion to her children coexists uneasily with her fear of losing herself in domesticity. Several generations later, the intersection of life and work continues to be one of the points of most profound anxiety in our society—an anxiety that affects not only women but also their husbands and children.

Whatever his flaws as a husband, Hyman was a consistently insightful interpreter of his wife’s work. He bitterly regretted the critical neglect and misreading she suffered during her lifetime. “For all her popularity, Shirley Jackson won surprisingly little recognition,” he wrote in an essay published after her death. “She received no awards or prizes, grants or fellowships; her name was often omitted from lists on which it clearly belonged.” He ended his lament with a prediction: “I think that the future will find her powerful visions of suffering and inhumanity increasingly significant and meaningful, and that Shirley Jackson’s work is among that small body of literature produced in our time that seems apt to survive.” Considering the revival that has taken place in recent years—nearly all of Jackson’s books are currently in print, with a new edition of previously uncollected and unpublished materials appearing in 2015—it seems safe to say that he was correct.

1.

CALIFORNIA

1916–1933

INTERVIEWER:

You were encouraged to write by your family?

JACKSON:

They couldn’t stop me.

—New York Post

, September 30, 1962

W

HEN THE SS

CALIFORNIA

, AN ELEGANT STEAMER OPERATED

by the Panama Pacific Line, departed San Francisco for New York City on August 12, 1933, via the Panama Canal, its passengers looked forward to a luxurious voyage. The world’s largest electrically propelled commercial vessel, the

California

featured a domed dining hall with Cuban mahogany furnishings, windowed staterooms for every passenger, and a first-class gentleman’s smoking room paneled in pine. The journey included passage through the Panama Canal, opened in 1914 and still a novelty. Travelers spent their days lounging by the various outdoor swimming pools and their nights in the formal ballroom, where a masquerade ball, held under “the witchery of a tropic moon,” capped each voyage.

Shirley Jackson, age sixteen, was not seduced by the promise of such entertainments. It was the summer before her senior year of high school, and her parents had uprooted her from her home state of California for a

new life in faraway Rochester, New York. Though the sun blazed overhead, a photograph snapped on deck captured the family dressed for a blustery day at sea, with Leslie, Shirley’s father, in his customary wool suit, and his wife, Geraldine, in a long coat with a fur collar, its lapel sporting a lavish spray of flowers. Shirley wore a loose black dress with short, puffy sleeves and a floppy white collar, topped with a white hat to protect her fair skin from the sun. The dress sagged around her chest and waist; even her white gloves fit her poorly. As she squinted into the sun, her expression was wary. Geraldine and Leslie, too, looked somber. Only Barry, her easygoing fourteen-year-old brother, appeared pleased about the journey.

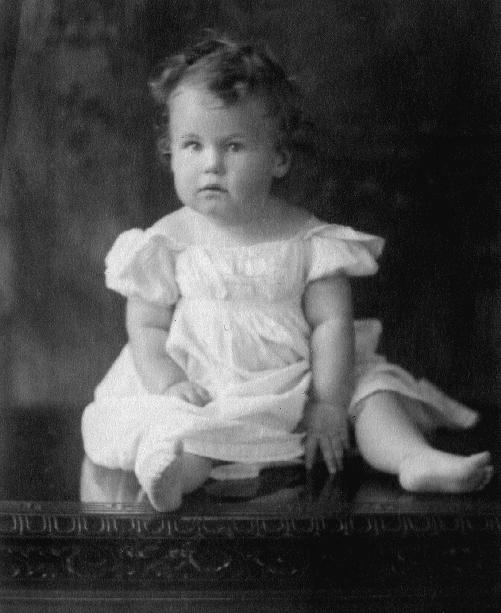

Shirley Jackson, 1915.

As desperate migrants from the Dust Bowl journeyed west overland in search of work and sustenance, the well-to-do Jacksons, unscathed by the Depression, were heading east. Leslie’s employer, the Traung Label and Lithograph Company, had grown steadily throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. Now it was merging with the Stecher Lithograph Company in Rochester, resulting in Leslie’s promotion and transfer. The Jacksons were trading a life of comfort and privilege on one coast—country clubs, social teas, garden parties—for a very similar life on the other. But though they were decorated with all the trappings of wealth, the photograph reveals them as ill at ease with one another, their stiff, formal body language radiating anxiety and mistrust.

It was wrenching to leave California, which Jackson would later remember as a lost Eden lush with avocados and other tropical delicacies then impossible to find on the East Coast. She traced her family history back to the roots of the burgeoning state: her great-great-grandfather, an architect, grew wealthy building mansions in San Francisco. She spent most of her childhood twenty miles south of the city, in tony Burlingame, “which means a suburb, and trees, and having to stop playing prisoner’s base when the streetlights went on in the evening, and sitting on a fence eating pomegranates with my dearest friend,” she later recalled. Before that first winter in Rochester, she would claim, she had never seen snow. Now she was embarking upon an entirely new life, a prospect that filled her with trepidation. She knew also, however, that she would have a rare chance to re-create herself, as had her ancestors, migrating westward nearly a century earlier.

HOUSES—ONE OF HER LIFETIME

obsessions and the gravitational center of much of her fiction—were in Jackson’s blood. “My grandfather was an architect, and his father, and

his

father,” she once wrote. “One of them built houses only for millionaires in California, and that was where the family wealth came from, and one of them was certain that houses could be made to stand on the sand dunes of San Francisco, and that was where the family wealth went.” Those first California houses, all built in the 1870s, were known as “millionaires’ palaces.” They were

the most opulent residences San Francisco had yet seen: one was built of local redwood painted white to look like marble, while another featured a private art gallery. These houses were owned by the men who created San Francisco—the “robber barons” who struck gold years after the Gold Rush by investing in the railroads connecting the western United States with the East. And they were built by Samuel C. Bugbee, San Francisco’s first architect and Jackson’s great-great-grandfather. Nearly a century later, she would turn to them for inspiration when she needed a model for the haunted house in her most famous novel.

When gold was first discovered at Sutter’s Mill, back in 1848, San Francisco, still in its infancy, was barely settled. New arrivals lived in canvas tents—poor shelter from the rainy weather. The city’s first buildings were made from ships run aground in the harbor. In 1849, the population was estimated at two thousand men and almost no women. David Douty Colton was among those who arrived that year, hoping to work in mining. Charles Crocker, who came out west a year later, would make his fortune in the dry goods business. Leland Stanford joined his brothers in their Sacramento grocery in 1852. By the early 1860s, Crocker and Stanford, along with Mark Hopkins and Collis Huntington, were major investors in the new transcontinental railroad; Colton served as their lawyer. In 1863, they broke ground in Sacramento for the Central Pacific Railroad, which would run east, traversing the Sierras and the desert, to meet the Union Pacific in Promontory, Utah, making the transcontinental journey in six days instead of six months.

Samuel Bugbee came to San Francisco around the same time as the men whose houses he would eventually build. Born in New Brunswick in 1812, he married Abbie Stephenson of Maine in 1836, with whom he had three sons: Sumner, John Stephenson, and Charles. The Bugbees spent the early years of their marriage in New England, their great-great-granddaughter’s later home and the setting for much of her fiction. But before long, the Gold Rush drew Samuel out west. He probably came to San Francisco in the early 1850s, his wife and sons joining him within a decade.

The flourishing city counted around 35,000 residents in 1852—a nearly twentyfold increase in just three years. By 1870, a year after the

transcontinental railroad was completed, its population had exploded again, to more than 500,000. All those new residents needed houses. Samuel C. Bugbee and Son (Charles, the youngest, had joined his father in business) was the first architectural practice in San Francisco. Sumner, the eldest, also trained as an architect and worked briefly with the firm. Their office, at 402 Montgomery Street, was situated prominently in the middle of the business district. Among Bugbee and Son’s creations were the California Theater (completed in 1869), Mills Hall at Oakland’s Mills College (1871), Wade Opera House (1876), and the Golden Gate Park Conservatory (1879).

Middle son John Stephenson, who would be Jackson’s great-grandfather, was the only male Bugbee not affiliated with the firm. A graduate of Harvard Law School, he practiced law in San Francisco and eventually spent nearly a decade in Alaska as a Superior Court judge. His wife, Annie Maxwell Greene of Massachusetts, traced her lineage to the Revolutionary War general Nathanael Greene and also counted among her relatives Julia Ward Howe, the activist and author of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” According to family lore, Annie left her family in Boston in 1864 and traveled alone all the way around Cape Horn to San Francisco, chaperoned by a minister. John Stephenson Bugbee met the boat at the port and the minister married the couple on deck. The bride brought with her a beautiful wooden music box the size of a small table, likely of European origin, which would become one of her great-granddaughter’s prize possessions. Jackson told her children that the music box, which could play a variety of melodies on zinc discs, was haunted: at times it seemed to turn itself on, but only to play its favorite selections. “It would start to play ‘Carnival of Venice’ at four o’clock in the morning,” Laurence Hyman, Jackson’s elder son, remembers. Even if Jackson claimed she hid the preferred disc, the music box would somehow manage to find it and play it. It was one of the many ways in which she delighted in putting a domestic twist on the supernatural.

AS SAN FRANCISCO SWELLED

in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the wealthy looked to Nob Hill—then known as California

Street Hill—to escape the congestion downtown. Richard Tobin, an Irish immigrant and lawyer who was among the founders of the Hibernia Savings and Loan Society, was one of the first to commission a grand house there from Bugbee and Son. In 1870, the

San Francisco Chronicle

reported that construction had begun on Tobin’s “large and elegant mansion” at the corner of California and Taylor Streets. The 5400-square-foot house, an elaborate Victorian, had a private chapel with stained-glass windows and a seventy-five-foot observatory tower. But it was quickly dwarfed by the monstrosities to come.

Attorney David Douty Colton’s “Italian palace,” an L-shaped, two-story Georgian-style building with a redwood frame, was completed in 1872. With a formal façade featuring marble steps guarded by two stone lions and Corinthian columns flanking the windows, it occupied no less than half a city block and cost around $75,000. Two years later, when construction began on a house for Leland Stanford—then president of the Central Pacific Railroad and former governor of California—a cable car line fought for by Colton ran up California Street, rendering the hill less formidable and the real estate even more valuable. Clad in granite, Stanford’s “Nob Hill castle” had six chimneys, bay windows on all four sides, and front doors made out of solid rosewood and mahogany, framed by triple columns. At 41,000 square feet, with fifty rooms, its cost was estimated between $1 million and $2 million. Stanford and his wife, Jane, commissioned Eadweard Muybridge, the pioneering mid-nineteenth-century photographer, to take pictures of the exterior and the sumptuous furnishings, which included allegorical paintings depicting the continents of the world, a frescoed ceiling, marble statuary, and a salon decorated in trompe l’oeil paintings and embroidery.

Charles Crocker’s home was the last of Bugbee and Son’s Nob Hill creations, and the most flamboyant. The 25,000-square-foot palazzo was situated at the top of the hill on the site of twelve smaller houses, which Crocker had bought and promptly demolished. The lone holdout was a German undertaker named Nicholas Yung, who demanded $12,000 for his property. Crocker, who would eventually spend around $3.5 million on his mansion, declined to pay. Instead, he built a forty-foot-tall “spite fence” surrounding Yung’s house. In retaliation, Yung

threatened to erect a coffin on his roof, visible above the fence, with a skull and crossbones painted on the side—simultaneously an advertisement for his business and a menacing memento mori. Even after Yung died in 1880, Crocker refused to take down the fence.

The Sundial

, Jackson’s fourth novel, revolves around the Hallorans, a disagreeable family who occupy a mansion at the top of a hill, surrounded by a stone wall. Crocker’s Second Empire-style palace went further: it was enclosed by a wall of solid granite and crowned with a seventy-six-foot tower. A party given there in 1879 was the San Francisco social event of the decade, “an entertainment that will stand without rival possibly for years to come as regards sumptuousness, tastefulness of decorative art and nicety, elaborateness of ornamentation and illumination and prodigality of expenditure,” a local newspaper reported. The menu included two kinds of oysters and nineteenth-century delicacies such as “Terrapine à la Maryland,” “Mignons de Foie Grasse à la Russe,” and “Galantine de Dinde au Suprême.” Mrs. Crocker wore a burgundy velvet dress and an estimated $100,000 worth of diamonds.