Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (5 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

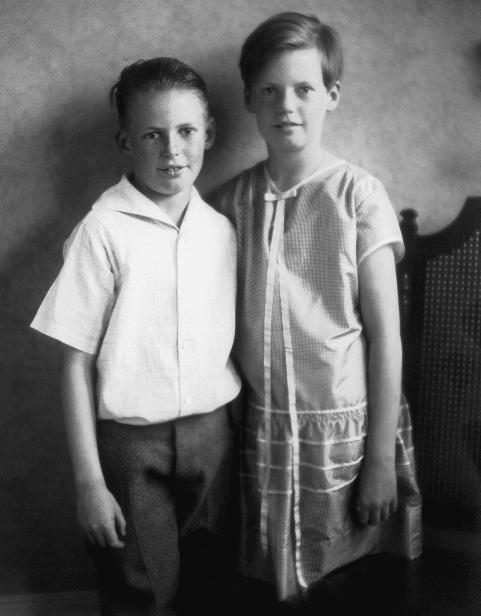

“She was a lady, Geraldine was,” Laurence Hyman remembers. And she tried valiantly to shape her daughter in her image. In one of the earliest photographs of Shirley, the little girl wears an immaculate

ruffled white party dress, white shoes and socks, and a giant starched bow nearly the size of her head. But it must have been clear early on that Shirley would not conform to Geraldine’s ambitions for her. “I don’t think Geraldine was malevolent,” recalls Barry Hyman, Jackson’s youngest child. “She was just a deeply conventional woman who was horrified by the idea that her daughter was not going to be deeply conventional.” “Geraldine wanted a pretty little girl, and what she got was a lumpish redhead,” Joanne Hyman says bluntly. When Barry Jackson—handsome, blond, athletic—arrived two years after his sister, it must have quickly become obvious which child Geraldine favored. Her criticism of her daughter—Shirley’s appearance (especially her weight), her housekeeping, her child-rearing practices—never relented. Even after Geraldine and Leslie eventually moved back to California, leaving Shirley settled permanently in the East, Geraldine continued to nag and needle her daughter by mail. Though Jackson would later express her distress over the hostile letters she received from readers in the wake of “The Lottery,” that sudden deluge, largely from faceless strangers, seems less damaging than the drops of poison she grew accustomed to receiving from her mother every few months—and to which, almost without fail, she dutifully and cheerfully responded.

Shirley Jackson with her brother, Barry, in San Francisco, early 1920s.

Jackson’s awareness that her mother had never loved her unconditionally—if at all—would be a source of sadness well into adulthood. Aside from a single angry letter that she did not send, she never gave voice to her feelings of rejection. But she expressed them in other ways. All the heroines of her novels are essentially motherless—if not lacking a mother entirely, then victims of loveless mothering. Many of her books include acts of matricide, either unconscious or deliberate.

THE UNOFFICIAL MOTTO

of Burlingame, California, which for years adorned a mural painted on City Hall, reflected its founders’ unapologetic sense of entitlement: “Living in Burlingame is a special privilege.” By June 1926, when Shirley was nine, the Jacksons had installed themselves in the modern new house Maxwell Bugbee had designed for them (and his wife) in the growing suburb south of San Francisco—“far enough away . . . to have palm trees in the gardens,” Jackson would later write. It was a privilege Leslie and Geraldine felt they had earned: she owing to her wealth and family pedigree, he through his hard work and providential marriage. Socially conservative, xenophobic, and openly racist—reflective of the nativist prejudices common among the American upper classes of their period—they fit comfortably in the elite enclave.

During the early years of Shirley’s life—which were also the first few years of her parents’ marriage—the Jacksons had moved often, even itinerantly. When Shirley was born, they were likely living at 1060 Clayton Street, in the elegant Ashbury Heights neighborhood of San Francisco. They spent a couple of years in San Anselmo, a bucolic town in Marin County, but by the beginning of 1920, they were back in the city, renting a house on Twenty-Eighth Avenue between Anza Street and Balboa Street, in the Richmond district, just a few blocks north of Golden Gate Park. Leslie had advanced to secretary at the lithography firm, and there was a servant girl to help with the children—Shirley had just turned three, and her brother, Barry, was one. Geraldine’s parents, Maxwell and Mimi, lived next door with their adult son, Clifford, a radio mechanic who would remain a bachelor all his life. The following

year, the family, which by that time included Mimi, moved back to Ashbury Heights, to a newly built house at 20 Ashbury Terrace, where Mimi hung out a shingle as a Christian Science practitioner—that is, a spiritual healer. Set high upon a hill, it was literally a move up. But they would stay there only a few years. Leslie and Geraldine had set their sights even higher.

The town of Burlingame was named for Anson Burlingame, an American diplomat in China, who in 1866 bought an estate there once owned by William C. Ralston, a banker. Burlingame died before he could move in, and the land wound up in the hands of Ralston’s son-in-law, Francis G. Newlands, a congressman and senator who had been influential in the development of Chevy Chase, Maryland, an affluent suburb of Washington, D.C. He envisioned Burlingame according to a similar model, with large estates surrounding an exclusive club—the country headquarters for San Francisco’s high society.

When the Burlingame Country Club was founded, in 1893, the town consisted mainly of horse farms and dairies. Nestled among them were a few estates owned by some of California’s wealthiest families, including the Mills estate, built by Bank of California executive Darius Ogden Mills, and nearby Black Hawk, owned by Mills’s sister Adeline and her husband, Ansel I. Easton, uncle of the photographer Ansel Adams. The area, according to a local historian, was “like something out of England—huge country manors surrounded by a handful of local people who helped keep the large manors running.” Most of the streets were unpaved, and frequent flooding from Burlingame Creek—which ran smack through the middle of town until it was channeled underground decades later—meant that they often turned to mud. There were no shops or services aside from an itinerant vegetable farmer who passed through several times a week. Nonetheless, a tourist brochure printed in 1904 described it as “perhaps the most exclusive hometown in California.”

The San Francisco earthquake of 1906 was powerful enough to rattle pantries and knock down chimneys in Burlingame. Soon the exclusive enclave was host to a flood of evacuees, many of whom were attracted by its easy commuting access to the city. By the following year, the

population had quadrupled, to 1000. The new residents, accustomed to the conveniences of city living, clashed with some of the old-timers over their demands for civic improvements such as paved roads and a municipal water system. The result was that the “hill people”—including the owners of most of the largest estates—formed a separate town, called Hillsborough. (To the chagrin of longtime Burlingamers, the Burlingame Country Club fell within the new Hillsborough city limits.) In 1912, the paving of El Camino Real, which runs directly through Burlingame, set the town on the path of one of California’s first state highways. That decade saw Burlingame nearly triple in size, reaching more than than 4000 residents by 1920. It also gained a library, an elementary school, two movie houses, and six churches.

A guidebook published in 1915 described Burlingame as “new, modern, spick and span—flowers, lawns, trellises, porticos, portolas, snug little individual garages. The whole place has an atmosphere of success.” The town prided itself upon its friendliness: the official slogan was “You are a stranger here but once.” That hospitality, not surprisingly, was extended only to white Christians. In

The Road Through the Wall

(1948), set in a town modeled on Burlingame, Jackson depicts racism and anti-Semitism among neighbors on a close-knit street virtually identical to the one where she grew up. At a time when small towns were considerably more provincial than they are today, Burlingame was one of the most insular—claustrophobically so. As the population exploded—in the years between 1920 and 1927, it nearly tripled yet again, to 12,000—houses were built so close together, with deep gardens but narrow side yards, that two people leaning out of facing windows could nearly shake hands. That proximity, in the novel, serves as a breeding ground for gossip and animosity.

The commuter town’s rapid growth stemmed in part from the growing popularity of the automobile. Burlingame became a hub for automobile dealerships, and by the end of the 1920s, one in three residents would own a car, compared with one in five Americans. The names of new car buyers were printed in the local newspaper in celebration of the community’s prosperity. At a time when the average American family earned $1200 per year, the typical Burlingame home cost around $7500.

Even the Depression did little to dampen Burlingame’s cheer: residents were encouraged to support the economy by holding “prosperity parties,” teachers donated six days’ pay over six months to help the unemployed, and a portion of movie revenues was given to charity.

The Jacksons arrived in the middle of the 1920s boom. Their new home, a handsome two-story brick house with a front gable and a deep garden out back, was located at 1609 Forest View Road (now Forest View Avenue). It was only a few blocks from McKinley Elementary School, where Shirley and her brother enrolled, and a short stroll from the main commercial strip on Broadway. The Christian Science church was practically around the corner. Leslie commuted daily to his job at the rapidly expanding Traung Company. Even as the Depression hit, he continued to be promoted.

The end of Forest View Road marked the official border of Burlingame. Beyond lay the “Millionaire Colony,” as Hillsborough was then nicknamed. From their backyard, the Jacksons might have been able to see into the garden of the nearest estate, built a decade earlier

by George Newhall, son of an auctioneer and land speculator named Henry Newhall. Known as La Dolphine, the Newhall mansion was modeled after the Petit Trianon at Versailles, with a formal garden and a 175-foot-long driveway lined with pink and white hawthorn trees. The architect was Lewis Hobart, whose other commissions included a number of major buildings in and around San Francisco, among them—coincidentally—an estate for William Crocker, Charles’s son, in Hillsborough, built after the family home in San Francisco was destroyed by the earthquake.

Shirley and Barry, around the time of the move to Burlingame.

The action in

The Road Through the Wall

, set in 1936 in the fictional town of Cabrillo, California, takes place on Pepper Street, which happens to have been the name of one of the streets intersecting the Jacksons’ block of Forest View Road (its name was later changed to Newhall). Cortez Avenue, which also figures in the novel, was a few blocks away. And the estate behind the wall, one of the novel’s key symbols, was almost certainly modeled on La Dolphine, which was subdivided in 1940—around the same time as the estate in the novel is. In her notes for

The Road Through the Wall

, Jackson wrote out character sketches for each of the families and included, in parentheses, the names of their real-world models. She even mapped out the houses on her fictionalized Pepper Street, depicting them directly adjacent to one another—just as close as they were in reality.

As faithfully as Jackson followed the physical contours of the neighborhood, her novel’s plot boldly clashes with the official version of Burlingame as a town of cheerful families living in tasteful homes. Only in “The Lottery” can a less appealing set of neighbors be found in Jackson’s fiction. “The weather falls more gently on some places than on others, the world looks down more paternally on some people,” she wrote in its richly ironic opening lines. “Some spots are proverbially warm, and keep, through falling snow, their untarnished reputations as summer resorts; some people are automatically above suspicion.” Of course, in Jackson’s work no one is ever above suspicion. An uncommonly close observer even as a child, she had reason to speculate that beneath the sunny surfaces of her neighbors’ lives lay darker secrets: infidelity, racial and ethnic prejudice, basic cruelty. The novel’s children—Jackson’s

peers—are treated with at least as much gravity as the adults, whom they easily equal in connivance and brutality. Harriet Merriam, an outsider who is clearly a stand-in for Shirley, commits cruelties in order to fit in with the other children on the block. One girl is mentally disabled, and several of the children manipulate her into buying them fancy presents. Marilyn, the only Jewish child, is mocked for not celebrating Christmas. The petty crimes and misdemeanors accelerate to the crisis at the novel’s conclusion, in which a child is brutally murdered while the adults engage in drunken antics at a garden party.