Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (59 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

Shirley Jackson, mid-1950s.

While Americans worried about a hypothetical disaster at home, the bomb’s repercussions could already be felt abroad. Meteorologists had miscalculated both the power of the explosion and the direction of the wind carrying radioactive fallout, which threatened two dozen American sailors on the Pacific island of Rongerik, more than two hundred people on the Marshall Islands, and the Japanese crew of a small fishing boat that happened, unluckily, to be in the area. One of the Japanese fishermen witnessed the explosion. “The sun’s rising in the west!” he

called to his shipmates. Two hours later, ashes began to rain down on them. By the time the boat pulled into port, several weeks later, many of the crew were suffering from radiation sickness; one eventually died.

Apocalypse was in the air, quite literally. A decade later, cultural critic Susan Sontag would argue that the citizens of the world suffered a collective trauma in the mid-twentieth century “when it became clear that, from now on to the end of human history, every person would spend his individual life under the threat not only of individual death, which is certain, but of something almost insupportable psychologically—collective incineration and extinction which could come at any time, virtually without warning.” One expression of that trauma, Sontag wrote, was the sudden increase in science fiction films during the 1950s and 1960s, which often take nuclear war as a theme or a subtext. In

The War of the Worlds

(1953), based loosely on the H. G. Wells novel, creatures from Mars invade Earth because their planet has become too cold. In

The Incredible Shrinking Man

(1957), the main character is shrunk by a blast of radiation.

The Mysterians

(1959) features extraterrestrials who have destroyed their own planet with nuclear warfare.

The World, the Flesh and the Devil

(1959) is devoted to the Robinson Crusoe–style fantasy of occupying a deserted city and starting a new civilization. And the Soviet launch of Sputnik I in October 1957, kicking off the “space race,” not only demonstrated the Soviet Union’s superiority in the arms race, but also triggered enormous anxiety about new disasters that might rain down from the sky.

Despite the popularity of this genre in the 1950s, Jackson wrote only one published story that truly qualifies as science fiction: “Bulletin,” a whimsical vignette from 1953 about a professor who travels ahead to the year 2123. His time machine returns empty but for a few fragmentary documents that show both how drastically the world has changed and how it hasn’t, such as an American history exam that refers to “Roosevelt-san” and “Churchill III” and contains a list of true-or-false statements that includes “The cat was at one time tame, and used in domestic service.” But in

The Sundial

, a social satire, she took the mood of impending apocalypse and turned it on its head.

The Sundial

, Jackson said, was written from the inside out.

“Prominent in every book I had ever written was a little symbolic set that I think of as a heaven-wall-gate arrangement,” she told an audience at Syracuse in the summer of 1957, shortly after finishing the manuscript. In each of her novels, she said, “I find a wall surrounding some forbidden, lovely secret, and in this wall a gate that cannot be passed.” Somehow, she had never been able to get through the wall, and it occurred to her that the thing to do was to start from the inside and work her way out. “What happened, of course, was the end of the world. I had set myself up nicely within the wall inside a big strange house I found there, locked the gates behind me, and discovered that the only way to stay there with any degree of security was to destroy, utterly, everything outside.”

Starting with

The Sundial

, each of Jackson’s final three completed novels begins and ends with a house. Here it is the Halloran estate, built several generations earlier by the first Mr. Halloran and now occupied by dysfunctional descendants: Richard, a senile old man, and his wife, Orianna; Richard’s sister, known to all as Aunt Fanny; Maryjane, widow of Lionel, who was Richard and Orianna’s son (when the novel begins, he has just died under suspicious circumstances, and Maryjane believes that her mother-in-law pushed him down the stairs to ensure her ownership of the house); Fancy, Maryjane’s daughter; and a small crew of servants and hangers-on. Like the estate in

The Road Through the Wall

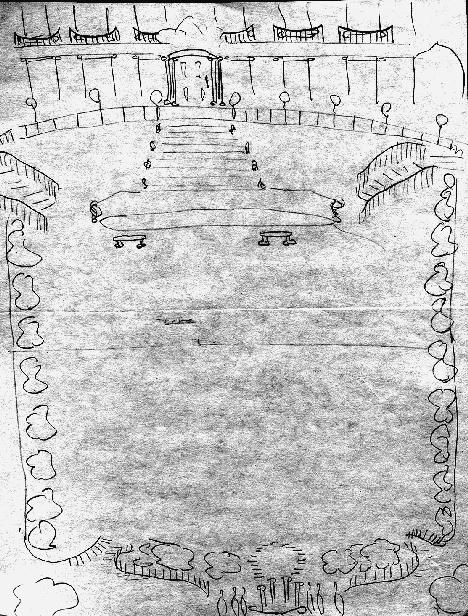

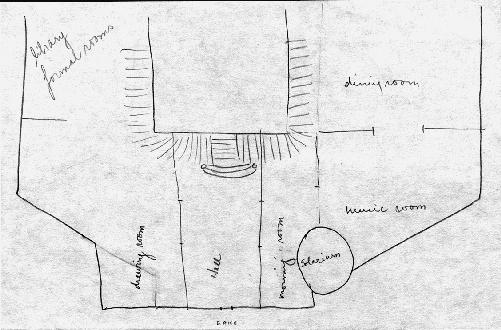

, the house is separated from the rest of the world by a stone wall that completely encircles it, “so that all inside the wall was Halloran, all outside was not.” The first Mr. Halloran, who made his fortune in some unspecified business, built the house because he “could think of nothing better to do with his money than set up his own world.” Everything was constructed according to a strict order: the tiles on the terrace and the marble pillars holding up the balustrade all perfectly symmetrical, a precisely square blue pool, a “summer house built like a temple to some minor mathematical god.” Only the sundial, in the midst of it all, is off center, a reminder “that the human eye is unable to look unblinded upon mathematical perfection.” Jackson planned the design meticulously, illustrating her notes for the novel with sketches showing the layout of the house and gardens.

One morning before sunrise, Aunt Fanny wanders into the garden

and has a vision in which her father speaks to her of an impending apocalypse. “Humanity, as an experiment, has failed,” Aunt Fanny declares grandly to the others. (“Splendid. I was getting very tired of all of them,” her sister-in-law responds.) In “one night of utter disaster,” the entire world will be destroyed, with only the house left standing. Its inhabitants, emerging “safe and pure,” will be “charged with the future of humanity; when they came forth from the house it would be into a world clean and silent, their inheritance.” The date of the apocalypse is set for August 30, about three months hence; Jackson later joked that she chose it because it was also her deadline. In the novel, as per her usual practice, no year is specified and there are few markers of temporality. The story could be set in the past or in the future—it does not matter.

Jackson’s sketch of the Halloran estate’s garden for

The Sundial.

Jackson’s sketch of the Halloran estate (interior).

The critic R. W. B. Lewis, an acquaintance of Jackson and Hyman’s, wrote that apocalyptic fiction has “a pervasive sense of the preposterous: of the end of the world not only as imminent and titanic, but also as absurd.” Perhaps Jackson’s funniest novel,

The Sundial

, like Stanley Kubrick’s classic film

Dr. Strangelove

(1964), derives much of its very black comedy from the spectacle of how singularly unfit its characters are to contend with an event of such cosmic significance. If they are the “chosen people,” as one character puts it, the future of humanity looks very bleak indeed: these inheritors of the earth are petty and self-indulgent, preoccupied with their social class (which they lord over the villagers who live literally below their house high on a hill) and their interfamilial squabbles. Aunt Fanny is insufferably passive-aggressive (“No one needs to worry over me, thank you”); Orianna, her detested sister-in-law, enlists members of the household to spy on one another and stands behind her husband’s wheelchair so that he cannot see the boredom on her face. Shortly after their honeymoon, her husband asked if she married him for his money. “Well, that, and the house,” she told him matter-of-factly. All the house’s residents are utterly certain of their own superiority. At one point they are visited by representatives of the True Believers, a doomsday cult preparing for the imminent arrival of spacemen from Saturn to take them away. In a very funny scene, the True Believers, who might be characters out of one of those campy

1950s science fiction films, attempt to assess the Hallorans’ preparedness for the apocalypse—do they eat meat or drink alcohol? do they use metal fastenings on their clothes?—and are roundly ejected from the mansion.

Jackson said more than once that

The Sundial

was her favorite of her novels: “Nothing I have ever written has given me so much pleasure,” she claimed in her lecture about the book. After her two-year block, it poured out of her quickly and easily, untroubled by the usual false starts and self-doubt: she began it in fall 1956, around the time of President Eisenhower’s reelection, and was finished the following summer, just before the Sputnik launch. Her enjoyment is evident in the novel’s comedy, especially her lengthy detailing of the housekeeping necessary to prepare for the end of the world. Aunt Fanny startles the proprietress of the village bookshop by asking for a Boy Scout handbook on surviving in the wild, as well as elementary textbooks on engineering and chemistry and a guide to herbs, announcing that she has “an immediate need for a good deal of practical information on primitive living.” (The villagers, incidentally, have little to redeem them: they get their lifeblood from tourists who make pilgrimages to the site of a grisly murder some years ago in which a local teenager killed her father, mother, and younger brothers with a hammer, Lizzie Borden–style.) Eventually the Hallorans will remove all the books from the library and burn them in the barbecue pit, filling the shelves with antihistamines, first-aid kits, instant coffee, suntan lotion, toilet paper, citronella, cigarettes, and other indispensables—perhaps a reflection of the midcentury mania for building bomb shelters. (A booklet issued by the U.S. government in the early 1950s, titled “You Can Survive,” gave helpful tips on what to store inside a bomb shelter.) But Jackson plays it coy when it comes to the actual moment of apocalypse. The book ends with the Hallorans—most of them, anyway—barricaded in the house, waiting.

The motto on a sundial normally contains a reference, often morbid, to the passing of time and the approach of death, such as “

Tempus fugit

” or “

Carpe diem

.” In an early draft, Jackson chose “It is later than you think”; after considering numerous options, most of them biblical—“Watch, for ye know not when the time is”; “The time is at hand”—she

settled on “What is this world?” The line comes from Dryden’s retelling of Chaucer’s “Knight’s Tale”: “What is this world? what asken men to have? / Now with his love, now in his colde grave / Allone withouten eny companye.” Particularly appropriate for the atomic age, it emphasizes our lack of control over our fate, and the speed at which our circumstances can change. It reminds us also that the Halloran estate, a world in itself, is a microcosm of our own world, intended to “contain everything”: a lake with swans, a pagoda, a maze and rose garden, items of silver and gold, a library stocked with marble busts and leather-bound books, and inspirational quotes—“When shall we live if not now?”—inscribed on the walls.

Like Elizabeth Richmond in

The Bird’s Nest

, the Hallorans are an extreme case, an exaggeration of a common human condition. But every family does create its own world, and every house is an expression of the world in which that family lives: its experiences, its history, its inside jokes and preoccupations. This is poignantly illustrated by Aunt Fanny, who preserves in the attic of the mansion a perfect replica of the apartment in which her parents lived before they moved to the estate: the knickknacks and photographs and books and Victrola in the living room (“this furniture had been built to endure, and endure it would”); the kitchen with oilcloth on the table and the high chair used by Aunt Fanny and her brother; beds made up in the bedrooms. A family, as Mrs. Halloran says at the end of the novel, is “a tiny island in a raging sea . . . a point of safety in a world of ruin.”