Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (62 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

Regardless of what exactly she saw, Jackson came back from New York eager to begin a new novel about a haunted house: “the kind of novel you really can’t read alone in a dark house at night.” But she needed a good house for inspiration. For some time she had been collecting postcards and newspaper clippings of old houses: Wallace Fowlie gave her some from France, and Hyman bought her a box of hundreds of postcards depicting houses from around the world. She and Laurence would sometimes drive around the back roads near North Bennington and look for houses that might be haunted. There were a lot of abandoned farmhouses, but nothing suitable: the New England houses were too square and neoclassical, a “type which wouldn’t be haunted in a million years.” She wanted something ornate, like the Château de Monte-Cristo, a turreted Renaissance castle built by Alexandre Dumas père; Neuschwanstein Castle, a fairy-tale-like Romanesque Revival palace in Bavaria; or Grim’s Dyke, a combination Gothic Revival/late Elizabethan mansion in London that had belonged to W. S. Gilbert. Closer to home, many have speculated that Jennings Hall, an ivy-covered gray stone mansion perched on a hill on the Bennington campus, was the model for Hill House, but there is no evidence for this: Jackson’s files contain no picture of it, and the house is much plainer than the others in her collection. A better local candidate is the Edward H. Everett mansion near Old Bennington, which at the time was being used as the novitiate of the Holy Cross Congregation and is now part of the campus of Southern Vermont College. The former home of a wealthy glass bottle manufacturer, the mansion was the site of a contentious legal dispute

between Everett’s daughters and his second wife. It is said—still—to be haunted by the ghost of Everett’s first wife, a woman dressed in white who roams the house and grounds. A picture of the mansion, suitably foreboding, is in Jackson’s files.

The Everett Mansion in Bennington, Vermont, shortly after its completion in 1912.

Unsatisfied with New England, Jackson turned to the West Coast, asking her parents to send pictures of the Winchester House in San Jose, California, or “pictures and information (particularly pictures) of any other big old california gingerbread houses.” Whether she remembered that some of those old “gingerbread houses” had been designed by her ancestors was unclear. But Geraldine responded at once with a handful of clippings, including images of the Crocker House, which she identified correctly as one of her great-grandfather’s creations. She also sent a tourist brochure for the Winchester House, now known as the Winchester Mystery House. Only forty miles from Burlingame, it had been built by Sarah Winchester, the widow of gun magnate William Wirt Winchester, after the death of her husband and daughter. A medium reportedly told her that spirits were taking revenge on her for all the people who had been killed by Winchester firearms. The only solution was to build a house that was in flux: as long as rooms, corridors,

and stairs were constantly added, the medium said, the confused spirits would not attack. Sarah Winchester followed her instructions, employing carpenters to work continually on the house for thirty-eight years, until her death in 1922. Its idiosyncratic design includes gables and turrets bursting out at all angles, corridors that lead nowhere, stairs with uneven risers, trapdoors, and ornamentation featuring spiderwebs and the number thirteen (Winchester believed both had spiritual significance). Hallways are as narrow as two feet; doors open both inward and outward in unexpected places, with some on the upper floors leading directly to a sudden drop. “An unguided person would be completely lost within fifty feet of the entrance,” warns the brochure. Hill House would incorporate some very similar features, including the disorienting layout, and the novel mentions the Winchester House.

Jackson’s architectural creation includes elements of many of her models, but she invested it with an emotional valence that was distinctly her invention. “No human eye can isolate the unhappy coincidence of line and place which suggests evil in the face of the house, and yet somehow a manic juxtaposition, a badly turned angle, some chance meeting of roof and sky, turned Hill House into a place of despair,” she writes. The house’s “face”—she does not call it a façade—seemed “awake, with a watchfulness from the blank windows and a touch of glee in the eyebrow of a cornice”; it “reared its great head back against the sky without concession to humanity.” Shown to her bedroom by Mrs. Dudley, the sinister housekeeper who seems to try deliberately to unnerve her (“We live over in the town, six miles away. . . . So there won’t be anyone around if you need help. . . . We couldn’t even hear you, in the night”), the protagonist, Eleanor Vance, finds even the geometry of the room unsettling: “It had an unbelievably faulty design which left it chillingly wrong in all its dimensions, so that the walls seemed always in one direction a fraction longer than the eye could endure, and in another direction a fraction less than the barest possible tolerable length.” Downstairs is a labyrinth of rooms, many windowless; the doors, hung off center, swing shut of their own accord. “A masterpiece of architectural misdirection,” one character calls it.

Now that Jackson had found her house, she needed ghosts. She

consulted a number of well-known historical accounts of haunted houses: the report of John Crichton-Stuart, who led a team of psychical researchers to investigate Ballechin House in Scotland in the late 1890s, as well as the book

An Adventure

, in which Charlotte Anne Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain, two British women on a European vacation, describe their uncanny experience of stumbling on a scene from the past while visiting the Petit Trianon, Madame du Barry’s house at Versailles. An episode late in

Hill House

, in which Eleanor and Theodora unexpectedly come upon a group of people—perhaps ghosts—picnicking in the grounds behind the house, shows the influence of their chronicle, as does Jackson’s use of the name Eleanor, found nowhere else in her work, for her main character. In her notes for the novel, Jackson refers to

An Adventure

as “one of the greatest ghost stories of all time.”

As Jackson began to write, further inspiration came from an unlikely source of the supernatural: the newspaper. In early 1958, the New York media reported on the curious case of a Long Island family apparently plagued by a poltergeist. One afternoon in early February, Mrs. Herrmann called her husband at the office to tell him that bottles in the family’s ranch house—“a symbol of orderly suburban family life,” wrote one reporter—were “blowing their tops”: their screw tops had spontaneously opened, spilling the contents everywhere. Next, while twelve-year-old Jimmy Herrmann was brushing his teeth, two bottles slid off the bathroom ledge and landed at his feet. The episodes continued almost daily for several weeks: a sugar bowl sitting on the dining table exploded while a detective was questioning the family; a ten-inch globe flew off a bookcase and hurtled across a hall to land at the feet of a visiting reporter; a statue of the Virgin Mary fell off a dresser. The story made the front page of

The New York Times

. Police, scientists, and parapsychologists all examined the case, but no single theory dominated. The disturbances eventually ceased as abruptly as they had begun.

The investigators focused on Jimmy Herrmann, who was around the same age as the girls who claimed to be plagued with witchcraft manifestations in Salem, and who was often in the room or nearby when the actions took place. It seemed impossible for him to be moving the objects physically, but a parapsychologist from Duke University who

visited the house suggested that Jimmy could be unconsciously exercising psychokinesis (also called parakinesis): using mental power to produce physical effects. An article about the case cited

Haunted People

, a book by Hereward Carrington and Nandor Fodor, psychical researchers who sought psychological explanations for phenomena that appeared to be supernatural. Carrington and Fodor point out that poltergeist-type episodes tend to take place in the vicinity of children around the age of puberty. “It is a legitimate inference that the life force which blossoming sexual powers represent is finding an abnormal outlet,” writes Fodor, whose theories were deeply influenced by Freudian psychology.

Jackson, curious, got a copy of Carrington and Fodor’s book. Even had she not acknowledged it to Fodor, its influence would be obvious. The vast majority of poltergeist incidents cited in

Haunted People

have one element in common—an element that appears over and over in the long list of cases the book references, and that will be immediately obvious to any reader of

Hill House

. The most frequent characteristic of a poltergeist manifestation, one that happened to have special resonance for Jackson, is precisely the same as the incident in the novel that originally brings Eleanor to the attention of Dr. Montague, the psychical investigator who organizes the visit to Hill House—an incident that took place when Eleanor was twelve. It is a shower of—of all things—stones. Like the missiles cast at Tessie Hutchinson by her neighbors, the ashes that rained down upon the unsuspecting crew of the Japanese fishing boat, or the satellites hurled into orbit only to come crashing back down, they are a small apocalypse in the air, a harbinger of disaster.

15.

THE HAUNTING OF

HILL HOUSE

, 1958–1959

we are afraid of being someone else and doing the things someone else wants us to do and of being taken and used by someone else, some other guilt-ridden conscience that lives on and on in our minds, something we build ourselves and never recognize, but this is fear, not a named sin. then it is fear itself, fear of self that I am writing about . . . fear and guilt and their destruction of identity. . . . why am i so afraid?

—unpublished document (1960)

“

T

HERE ARE GOING TO BE, EVENTUALLY, THE REASONS WHY

our marriage ends, and you ought to know that it will not be a vague sudden emotion, or quarrel, which drives—has driven—me away,” Shirley wrote in the long letter to Stanley in which she made clear how serious her grievances against him were. It is one of the most painful documents in her archive. She wrote of her loneliness in the face of his indifference to her and the children, his inveterate interest in other women, his belittling her, his obsessive devotion to teaching and to his

students, female all, “which leaves no room for other emotional involvement, not even a legitimate one at home.” She wondered if “this is the lot of wives and i have no cause to complain,” but she could not believe that. She concluded the letter with a final accusation. “you once wrote

me

a letter (i know you hate my remembering these things) telling me that i would never be lonely again. i think that was the first, the most dreadful, lie you ever told me.”

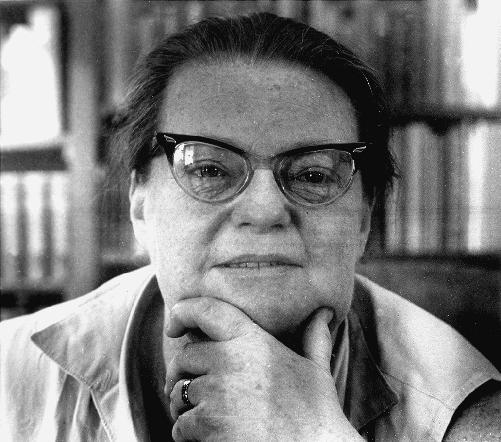

Shirley Jackson, late 1950s.

The letter is dated September 9, with no year. But a reference to the Suffield Writer-Reader Conference—Shirley told Stanley that she did not want him to accompany her there the following year—means that it was likely written in 1958, after the couple returned from a joint trip to the conference. Shirley was deep into writing

The Haunting of Hill House

that fall and completed the manuscript the following spring. Hill House—a house that contains nightmares and makes them manifest, in which fantasies of homecoming end in eternal solitude—is the ultimate metaphor for the Hymans’ symbiotic, tormented, yet intensely

committed marriage. Early drafts demonstrate that marriage was crucial to Shirley’s vision of the novel from the start. In one version, the sister of Erica, the protagonist (later to be named Eleanor), wants to set her up with a man. “Carrie wanted me to get married, for some inscrutable reason,” Erica says. “Perhaps she found the married state so excruciatingly disagreeable herself that it was the only thing bad enough she could think of to do to me.” To be married, Shirley always feared, was to lose her sense of self, to disintegrate—precisely what happens to Eleanor in the grip of the house.