Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (74 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

“The Bus” is the most complex of the three stories—a belated fourth

part, perhaps, of the late-1940s trilogy of “Pillar of Salt,” “The Daemon Lover,” and “The Tooth.” This time the protagonist is a disagreeable old woman traveling home alone at night. She falls asleep and is awakened by the bus driver, who abruptly puts her off at an empty crossroads she doesn’t recognize. A truck driver picks her up and takes her to a roadhouse that was once a Victorian mansion, but is now a tacky saloon. She tries to tell the innkeeper that she grew up in a house like this—“One of those good old houses that were made to stand forever”—but is met with jeers. She finds a bedroom that looks like her own childhood room and drifts off to sleep, the noise from downstairs reminding her of her mother singing in the drawing room. A rattling disturbs her, and she opens the closet to find it full of her childhood toys, become alive and malevolent. “Go away, old lady,” says her beautiful doll with golden curls, “go away.” She awakens to find herself still on the bus, being shaken by the bus driver, who is about to put her off at the very same crossroads where the bus had stopped in her dream. The story is ambiguous, but its underlying message is reminiscent of “Louisa, Please Come Home”: it is far easier to leave home than to find your way back again.

Jackson also managed to complete a well-paying piece for the

Saturday Evening Post

, a humorous riff on the same theme. Commissioned to write an essay for the magazine’s “Speaking Out” section, in which writers were encouraged to take extreme, irreverent positions on topics of interest, she chose the subject “No, I Don’t Want to Go to Europe.” A few years earlier, Hyman was pleased to be selected as a host to lead a literary European tour for a company specializing in themed trips—“twenty or so lonely schoolteachers decide that their summer might best be spent touring europe with stanley (not me; i am too ignorant; i am just to smile) pointing out spots of literary interest, like westminster abbey. . . . we say hemingwayhemingway and lead them to a bullfight”—but her colitis made the trip impossible. Now, she declared, she had never wanted to go anyway. First of all, she hated to fly; travel by boat was “slow and dirty, and you have to sleep with the bananas.” Even if it were possible to drive, she still wouldn’t want to go. “I don’t like leaving home in any case, but I dislike even more prying into someone

else’s country.” Her traveler friends came back full of insufferable stories about dining on balconies with contessas. The food was supposed to be terrible—“head cheese tastes like gefüllte fish”—and border crossings were terrifying. In any event, her husband “cannot get through the day without

The New York Times

” and she herself is “mortally afraid of practically everything.”

Although she found the piece difficult to write and the end result wasn’t up to her best work—it came out sounding more misanthropic than humorous—Jackson was happy to be working. “I am beginning to be more myself again, and more optimistic and enthusiastic than for a long time,” she wrote to Brandt. But she suffered a setback when the

Post

published her married name and address, unleashing a torrent of angry letters the likes of which she hadn’t seen since “The Lottery.” Not getting the joke, all the happy travelers she had caricatured wrote to castigate Jackson for her narrow-mindedness, one of them calling her piece a “nauseating little pack of distortions.” The episode, not surprisingly, gave her a difficult month.

Brandt was thrilled to see Jackson back at work, and even happier to learn that she and Hyman were planning a visit to New York in March 1964. To celebrate, she suggested a shopping trip to Bergdorf Goodman, the most exclusive department store in Manhattan, and lunch at the Four Seasons, then only six years old and the ultimate statement in American culinary modernism. That visit had to be postponed—Jackson got the flu—but she and Hyman did travel together to Indiana University, where he lectured and they were given a tour of the Institute for Sex Research, founded by Alfred Kinsey, and its pornography library. Jackson was intrigued: “Some of the material would make an interesting book; you couldn’t show it to your mother but my, wouldn’t it sell.” Dr. Toolan suggested that she book lecture dates into the following spring: the next one was scheduled for New York University in May. Sarah would accompany her—Jackson was still afraid to travel alone, though her goal was a solo trip to the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference that summer, where she had been invited to be on the faculty. “all of this i do with great trepidation, and batteries of pills, but i’ve been doing it. . . . each adventure takes a little less pushing from the doctor,” she

reported to her parents. At home, she kept her pills all around the house, in heart-shaped china boxes, so that she would always have them close at hand when she needed them.

Trepidation notwithstanding, the NYU lecture was a triumph. Brandt was out of town, so the Four Seasons lunch had to be postponed once again, but Jackson was in top form. She read an essay based on a set of rules for writing short stories she had drawn up the previous year, when Sarah had begun writing seriously; afterward, as if to demonstrate that the advice worked, she read a new story by her daughter. Titled “Notes for a Young Writer,” the lecture repeated some of the instructions she had been giving for years at Suffield—the writer’s main goal is to keep the reader’s attention; avoid anything extraneous to the narrative—but she phrased them with uncommon elegance. A story must have “a surface tension, which can be considerably stretched but not shattered”; it must keep as much as possible to one time and place and lead the reader naturally from one setting to another. Instead of wasting a sentence on a simple action—“They got in the car and drove home”—she advised using it to advance the plot: “On their way home in the car they saw the boy and the girl were still standing talking earnestly on the corner.” Characters don’t need to waste time in needless conversation: “It is not enough to let your characters talk as people usually talk because the way people usually talk is extremely dull.” Colorful words ought to be used sparingly for “seasoning,” if at all: “Every time you use a fancy word your reader is going to turn his head to look at it going by and sometimes he may not turn his head back again.” Simple language is usually best: “if your heroine’s hair is golden, call it yellow.” Textbooks insist that the beginning always must imply the ending, but “if you keep your story tight, with no swerving from the proper path, it will curl up quite naturally at the end.” During the question-and-answer session, Jackson was inevitably asked about “The Lottery.” “I hate it!” she answered. “I’ve lived with that thing fifteen years. Nobody will ever let me forget it.”

After the lecture, an editor from Doubleday approached Jackson. Would she be interested in doing a children’s chapter book for them—perhaps a fantasy in the style of the Oz books? Jackson was intrigued.

Brandt quickly shot down the idea—Jackson was already committed to Viking—but that was not enough to dissuade her. Within a month, she had embarked on a new children’s novel on the off chance that Covici might want it. “Since I do not seem to be writing any other kind of book, I thought this might be a good running start,” she told Brandt.

The Fair Land of Far

begins with an ordinary, unpopular girl named Anne, “the kind of person who always seems a stranger.” When she throws a party for herself, only two of her classmates show up. They are greeted with a surprise: because it is Anne’s birthday, the three of them will be granted access to the Fair Land of Far, reached through a hidden doorway in the kitchen. There she is no longer ordinary Anne, but a princess doted on by her parents, the king and queen. But as they prepare to celebrate, a strange present is delivered: a gigantic creature in a cage. Somehow it gets out, and in a rush of wings it seizes Anne and flies away with her. Someone must go after them—perhaps the two classmates who reluctantly showed up at the party.

If Jackson got much further than that, her work has been lost. But the book served its purpose: to provide an imaginary country to which she could retreat at a difficult time. A rehearsal, perhaps, for the real escape she planned to make as soon as she was ready.

18.

COME ALONG WITH ME

,

1964–1965

“I’ve just buried my husband,” I said.

“I’ve just buried mine,” she said.

“Isn’t it a relief?” I said.

“What?” she said.

“It was a very sad occasion,” I said.

“You’re right,” she said, “it’s a relief.”

—Come Along with Me

O

N APRIL 27, 1965, SHIRLEY JACKSON TOOK THE STAGE

of Syracuse University’s Gifford Auditorium. Wearing a bright red dress, with her hair loose down her back, she began to read the opening chapter of her new novel, speaking slowly and carefully:

I always believe in eating when I can. I had plenty of money and no name when I got off the train and even though I had had lunch in the dining car I liked the idea of stopping off for coffee and a doughnut while I decided exactly which way I intended to go, or which way I was intended to go. I do not believe in turning one way or another without consideration, but then neither do I

believe that anything is positively necessary at any given time. . . . I needed a name and a place to go; enjoyment and excitement and a fine high gleefulness I knew I could provide on my own.

Twenty-five years earlier, she had been interviewed on a college radio program called “I Want a Job,” in which people seeking employment could advertise themselves. Jackson said simply, “I want to write.” A month later, she left Syracuse with Hyman for New York, uncertain of her future.

Now she was the author of eight published books for adults, two

of them best sellers, one a National Book Award finalist. After more than two years of struggling with agoraphobia, she was at the start of a lecture tour that would take her to five different cities. She had two novels under way, with a lucrative new contract from Viking. While at Syracuse, she learned that in June the university planned to award her its prestigious Arents Medal for distinguished alumni. Leonard Brown was no longer alive to appreciate it, but in her lecture she credited her college education with starting her writing career. After she spoke, students swarmed her with questions about her writing methods, her work, and her time at Syracuse. By any measure, she was in top form.

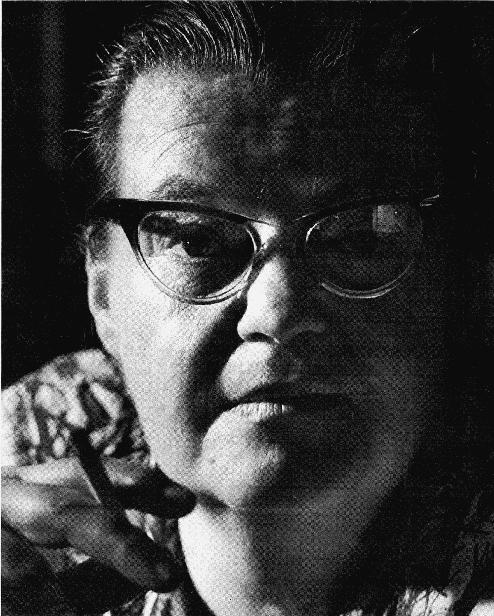

Jackson photographed by her son Laurence, early 1960s.

Less than three months later, she was dead.

IN AUGUST 1964

, Howard Nemerov and Jackson drove together along the winding roads from North Bennington to Bread Loaf Mountain. It was her first time attending the famous writers’ conference, founded in 1926 by her old friend John Farrar. In 1954, John Ciardi, a poet and regular columnist for the

Saturday Review

, had taken over as director. More formal and regulated than Suffield, it was the most prestigious summer program for writers. In addition to Robert Frost, who was a long-standing teacher there, many of the most important American writers came through the program as either fellows or faculty, including Eudora Welty, Carson McCullers, Anne Sexton, Ralph Ellison, and Joan Didion. “Being invited there meant something,” says Jerome Charyn, who was a Bread Loaf fellow in 1964.

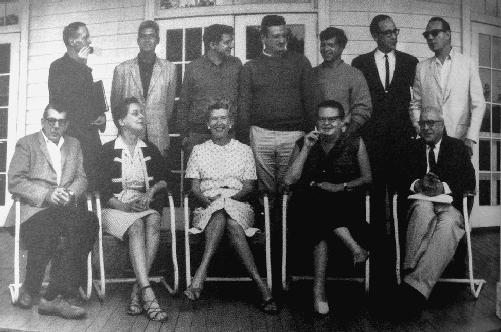

At meals, the faculty sat at a central table, separate from the students and fellows: they were “a little private group, eating together and gathering every day at twelve and five in our private little bar, where we had a bartender and an inexhaustible supply of bloody marys,” Jackson wrote later. Pictures of her with the other faculty that summer show her relaxed and smiling, often with a cigarette in her hand. For her public lecture, she delivered “Biography of a Story,” her account of the publication of and reaction to “The Lottery,” and read the story yet again. Her voice was “dour yet direct,” and projected a “quiet sense of doom,” recalled Mark Mirsky, another Bread Loaf fellow that summer. Hearing her read,

he said, was “a hypnotizing experience.” When she wasn’t teaching, she mainly rested.