Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (35 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

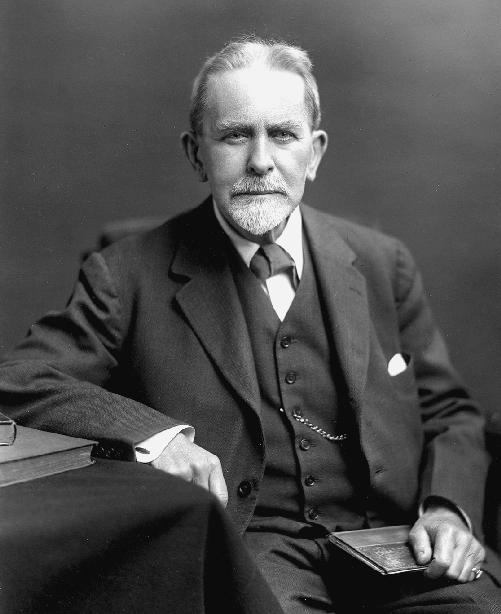

Sir James Frazer, mid-1930s. His book

The Golden Bough

deeply influenced Jackson

.

Details aside, it is stunning to think that this story composed in only a few hours—on this all the accounts agree—has proved to be one of the most read and discussed works of twentieth-century American fiction. Hyman told his friend Ben Belitt, a poet and fellow Bennington professor, that he recognized it as a masterpiece from the moment he read it. “It was the pure thing . . . the mythic thing you find in Greek literature,” Belitt commented. Other perceptive readers were also impressed from the start: “It is not likely the story will be forgotten, even though others of yours come along to assault,” John Farrar wrote to Jackson. But the reaction of Joseph Henry Jackson, the literary editor of the

San Francisco Chronicle

, was more typical—admiring, yet puzzled. “No one writes a story in a vacuum,” he wrote to Jackson. “Something pulled the trigger that set ‘The Lottery’ off in your mind. What was it?”

“The Lottery,” of course, did not come out of a vacuum. It was an obvious continuation of the preoccupations that had haunted Jackson for years. In a publicity memo written for Farrar, Straus around the time

The Road Through the Wall

appeared—only a month before “The Lottery” was written, if the March date on the draft is accurate—Jackson mentioned her enduring fondness for eighteenth-century English novels because of their “preservation of and insistence on a pattern superimposed precariously on the chaos of human development.” She continued: “I think it is the combination of these two that forms the background of everything I write—the sense which I feel, of a human and not very rational order struggling inadequately to keep in check forces of great destruction, which may be the devil and may be intellectual enlightenment.” In all her writing, the recurrent theme was “an insistence on the uncontrolled, unobserved wickedness of human behavior.”

Nowhere is this more obvious than in “The Lottery.” The story, with shades of

The Scarlet Letter

, unfolds in Jackson’s signature plain

style, which is perhaps what fooled some of its initial readers into believing it was fact. Much of it is devoted to a deceptively simple account of exactly how the ritual is conducted. Jackson sets the scene with her usual economy, depicting how the children, out of school for the summer, gather first, the boys horsing around and choosing “the smoothest and roundest stones” to fill their pockets. The men assemble next, “surveying their own children, speaking of planting and rain, tractors and taxes,” followed by the women, “wearing faded house dresses and sweaters. . . . They greeted one another and exchanged bits of gossip as they went to join their husbands.” Tessie Hutchinson arrives late; distracted by her housework, she forgot what day it was. “Wouldn’t have me leave m’dishes in the sink, now, would you?” she jokes. The details and the dialogue are virtually timeless: were it not for the reference to tractors, these villagers could be residents of Puritan Boston, gathered to witness the punishment of Hester Prynne.

The story proceeds calmly through every detail: the jovial manner of Mr. Summers, the retired man who conducts the ceremony, because he has “time and energy to devote to civic activities,” and who also runs the village square dances and the youth group; the black wooden box, shabby and splintered, from which the slips of paper will be drawn. Those who are missing must be accounted for—Clyde Dunbar is at home with a broken leg, so his wife will draw for him; Jack Watson draws for his mother, who seems to be a widow. (Looking back, the reader may wonder if the elder Watson was the victim of an earlier lottery.) Then the lottery proceeds, with the men coming up first to draw for their families.

Once it is discovered that Bill Hutchinson has drawn the slip of paper marked with a black dot, the story’s emotional climate alters drastically. Tessie, Bill’s wife, protests that he was rushed through the drawing. “It wasn’t fair!” she exclaims repeatedly. The others quiet her. The Hutchinsons—Bill, Tessie, their three children—draw again to determine who it will be. This time Tessie gets the black dot. “All right, folks,” says Mr. Summers, “let’s finish quickly.” The purpose of the stones becomes apparent as the story builds to its disturbing conclusion:

The children had stones already, and someone gave little Davy Hutchinson a few pebbles.

Tessie Hutchinson was in the center of a cleared space by now, and she held her hands out desperately as the villagers moved in on her. “It isn’t fair,” she said. A stone hit her on the side of the head.

Old Man Warner was saying, “Come on, come on, everyone.” Steve Adams was in the front of the crowd of villagers, with Mrs. Graves beside him.

“It isn’t fair, it isn’t right,” Mrs. Hutchinson screamed, and then they were upon her.

Jackson would claim that the only editorial change requested by

The New Yorker

was to change the date on which the lottery took place to June 27, so that it would match the cover date of the magazine (which was actually June 26). This is impossible to confirm, because the first few pages of the first draft have been lost. But it is the kind of change that editor Harold Ross, who insisted that the magazine’s fiction had to correspond with the season in which it was published, was known to make. In April, Kennedy tried to persuade the magazine to rush publication but was unsuccessful: had she succeeded, the date of the lottery might have been April 27 instead. The revised copy in Jackson’s archive reveals additional small changes—one or two by Hyman; others in response to marginal queries in Lobrano’s handwriting, asking her to make certain details of the process more clear. (In the first version of the story, she neglected to describe the actual drawing of lots.) Lobrano also was concerned that the story’s meaning was too opaque. “The most important thing is somehow to clarify your intention—that is, the underlying theme of the piece—just a bit more,” he told Jackson, suggesting that she amplify “one or two snatches of talk”—perhaps Old Man Warner’s complaint that nothing is good enough for young people. Could she give him a few more sentences about the dangers of breaking away from established tradition? “Not at all necessarily in such bald terms,” Lobrano cautioned. “He might even complain about the deviations from the original ritual.”

Jackson agreed to his request, adding one of the story’s key passages: Old Man Warner’s speech warning the villagers not to abandon the tradition.

“They do say,” Mr. Adams said to Old Man Warner, who stood next to him, “that over in the north village they’re talking of giving up the lottery.”

Old Man Warner snorted. “Pack of crazy fools,” he said. “Listening to the young folks, nothing’s good enough for

them

. Next thing you know, they’ll be wanting to go back to living in caves, nobody work any more, live

that

way for a while. Used to be a saying about ‘Lottery in June, corn be heavy soon.’ First thing you know, we’d all be eating stewed chickweed and acorns. There’s

always

been a lottery,” he added petulantly.

The townspeople take it for granted that the lottery serves a civic function, though that function is never articulated. “Some places have already quit lotteries,” one woman remarks. “Nothing but trouble in

that

,” Old Man Warner replies. Part of the reason is superstition: the lottery, which takes place near the summer solstice, fulfills the function of the ancient fertility rites detailed in

The Golden Bough

. (Hyman, with his ear for folklore, is said to have contributed the “corn be heavy soon” line, but if so, it must have been in conversation: that line is written on the manuscript in Jackson’s handwriting.) But more than that, the lottery is an event in which the entire town joins together. The participation of each member is so crucial that even little Davy Hutchinson must join in throwing pebbles at his mother. Tessie’s friend Mrs. Delacroix, one of the kindlier characters, will choose a stone “so large she had to pick it up with both hands.”

Even with Jackson’s clarifications, the meaning of “The Lottery” was not at all obvious to

The New Yorker

’s editors. She would later tell Thurber that when Lobrano called to say the magazine had accepted the story, he asked if she wanted to comment on its meaning. “I could not—having concentrated only on the important fact he had mentioned, which was that they were buying the story,” she said. (It was her first

piece to appear in

The New Yorker

since “It Isn’t the Money I Mind,” in August 1945, nearly three years earlier.) Lobrano continued to push, asking if the story was about the ignorance of superstition, or if it could be considered an allegory that made its point by ironically juxtaposing ancient customs with a modern setting. Sure, she said, that sounded fine. “Good,” Lobrano answered, “that’s what Mr. Ross thought it meant.”

By the late 1940s, the magazine’s fiction was starting to break free of the “bright, beautiful, but dead” style that Lionel Trilling had savaged in his 1942 essay for

The Nation

. Fiction writers who had their first stories in the magazine during those years included Nabokov, Salinger (whose

New Yorker

debut, “Slight Rebellion off Madison,” came in 1946 after two solid years of rejection), Stafford, Roald Dahl, and V. S. Pritchett. Cheever’s “The Enormous Radio” (1947) showed the magazine’s tastes evolving to embrace work that might previously have been thought too weird or difficult. A young couple, middle-class New Yorkers who live in a typical high-rise, mysteriously receive a new radio. Trying to tune it to her favorite station, the wife discovers that the radio picks up her neighbors’ conversations. She listens obsessively to the vicious fights that go on behind their sedately closed doors and eventually grows despondent. “We’ve never been like that, have we, darling?” she begs her husband to reassure her. Of course, the reader knows that these two are just as secretly wretched as all the rest.

Ross, who frequently complained about the grim stories the magazine was running and was famously resistant to anything that smacked of obscurity, initially balked at “The Enormous Radio.” “He’d say, ‘Goddammit, Cheever, why do you write these fucking gloomy goddamm stories!’ And then he’d say, ‘But I have to buy them. I don’t know why,’ ” Cheever recalled. Nevertheless, Ross supported the publication of “The Lottery” when Jackson resubmitted it in April. The only dissenter among the editors was William Maxwell, who found it “contrived” and “heavy-handed.” Among the writers, opinions were more divided, as Brendan Gill, then a young staffer at the magazine, cheekily informed Jackson. “I think, and have thought from the second I finished it, that it is one of the best stories (two or three or four best) that the magazine ever printed,” Gill wrote to her. “Lobrano thinks it’s

overwhelming, which—tell it not in Gath—surprises and delights me. On the other hand, Mitchell, Liebling, and others are as opposed to it as I am in favor of it.”

Despite the portentous way in which she would describe the story’s composition, Jackson presented herself as having been utterly unaware that anything unusual would happen upon its publication. And indeed, nothing about

The New Yorker

of June 26, 1948, suggested that it was something other than an ordinary issue of the magazine. The cover depicted a row of people fishing on a darkened beach, illuminated by the glow of campfires. There were ads for Dewar’s, Pontiac, United Airlines, Elizabeth Arden, Tiffany, DuMont televisions, and the new Pitney-Bowes postage meter. The “Talk of the Town” section included humorous pieces about knickers coming back in style and the process of adapting subway turnstiles for the imminent fare increase from a nickel to a dime. “The Lottery” was the second piece in the issue, between a short story by Sylvia Townsend Warner and an article from Argentina by Philip Hamburger about the corruption of the Peróns. The magazine also included a review of women cabaret singers, among them Ella Fitzgerald; a humor column devoted largely to the upcoming Republican presidential convention; a “Letter from Paris” by Janet Flanner; and a long review of Evelyn Waugh’s novel

The Loved One

by Wolcott Gibbs. Aside from the bombshell on page 25, there was nothing unusual about it at all.

THE FIRST LETTERS

were dated June 24, just after the issue hit newsstands. “Shirley Jackson’s ‘The Lottery’ . . . despite a certain skill of expression, impresses me as utterly pointless,” wrote Mrs. Victor Wouk of Park Avenue, who wondered whether Jackson was “not overly preoccupied with the gruesome.” “If the sole purpose . . . was to give the reader a nasty impact it was quite satisfactory, I suppose,” wrote Walter Snowdon of East Thirty-fifth Street. “I frankly confess to being completely baffled by Shirley Jackson’s ‘The Lottery,’ ” wrote Miriam Friend, a young mother living in Roselle, New Jersey, asking the editors to send an explanation before she and her husband “scratch right

through our scalps” trying to figure it out. Interviewed sixty-five years later, Friend still remembered how upsetting she had found the story.