Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (36 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

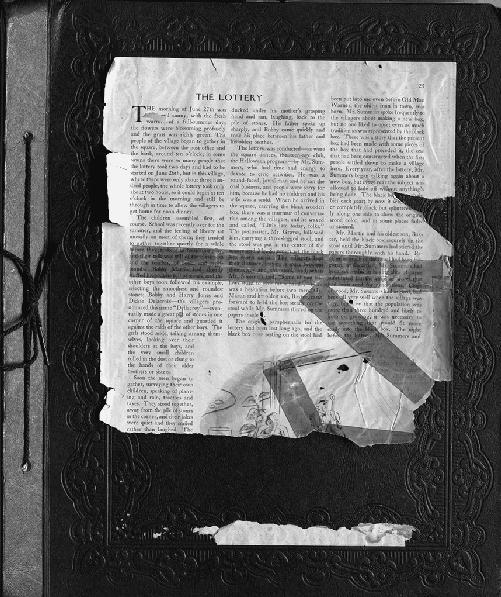

Jackson kept many of the letters she received about “The Lottery” in a large leather-bound scrapbook.

These were the start of a torrent of letters that

The New Yorker

would receive about “The Lottery.” By now the story is so familiar as a cultural touchstone that it is hard to remember how uncanny it originally seemed: “outrageous,” “gruesome,” “shocking,” or just “utterly pointless,” in the words of some of the readers who were moved to write to the magazine or to Jackson personally. Within a month there were nearly a hundred letters, “not counting two newspaper columns and ten notes canceling subscriptions,” Hyman reported cheerfully to Ben Zimmerman. By the beginning of August, the total was up to 150, and more were starting to come in from abroad. The magazine issued a press

release to say it had never before received so much mail in response to a work of fiction.

In “Biography of a Story,” Jackson gave the final total as more than 300 letters. Only 13 were kind, she claimed, “and they were mostly from friends.” (One had overheard people on the Fifth Avenue bus saying to each other, “Did you read that story in

The New Yorker

?”) The rest, she reported with mordant humor, were dominated by three main themes: “bewilderment, speculation, and plain old-fashioned abuse.” Readers wanted to know where such lotteries were held, and whether they could go and watch; they threatened to cancel their subscriptions; they declared the story a piece of trash. If the letter writers “could be considered to give any accurate cross section of the reading public . . . I would stop writing now,” she concluded.

Jackson probably did not exaggerate the sheer number of letters. A giant scrapbook in her archive contains nearly 150 of them from the summer of 1948 alone, and she would receive letters about “The Lottery” for the rest of her life. But though there were some canceled subscriptions and a fair share of name-calling, the vast majority of the letter writers were not hostile, simply confused. More than anything else, they wanted to understand what the story meant. The response of one Connecticut woman was typical. “Gentlemen,” she wrote, “I have read ‘The Lottery’ three times with increasing shock and horror. . . . Cannot decide whether [Shirley Jackson] is a genius or a female and more subtle version of Orson Welles.”

Although a decade had already passed since Welles’s famous broadcast of

War of the Worlds

, some did take the story for a factual report. “I think your story is based on fact,” wrote a professor at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. “Am I right? As a psychiatrist, I am fascinated by the psychodynamic possibilities suggested by this anachronistic ritual.” Stirling Silliphant, a producer at Twentieth Century-Fox, was also fooled: “All of us here have been grimly moved by Shirley Jackson’s story. . . . Was it purely an imaginative flight, or do such tribunal rituals still exist and, if so, where?” Andree L. Eilert, a fiction writer who had once (and only once) had her own byline in

The New Yorker

, wondered if “mass sadism” was still a part of ordinary life in New England, “or in equally enlightened

regions.” Nahum Medalia, a professor of sociology at Harvard, also thought the story might be factual, though he was more admiring: “It is a wonderful story, and it kept me very cold on the hot morning when I read it.” But the fact that so many of the readers accepted “The Lottery” as truthful is less astonishing than it now seems, since

The New Yorker

at the time did not designate stories as fact or fiction as it does today, and the “casuals,” or humorous essays, were generally understood as falling somewhere in between.

Arthur L. Kroeber, an anthropologist at the University of California, Berkeley, wondered about Jackson’s motivations: “If Shirley Jackson’s intent was to symbolize into complete mystification, and at the same time be gratuitously disagreeable, she certainly succeeded.” Kroeber’s daughter, the novelist Ursula K. Le Guin, was nineteen when “The Lottery” came out, and remembers that her father was indignant about the story “because as a social anthropologist he felt that she didn’t, and couldn’t, tell us how the lottery could come to be an accepted social institution.” Since the fantasy was presented “with all the trappings of contemporary realism,” Le Guin says, her father felt that Jackson was “pulling a fast one” on the reader. Jackson’s literary friends were no less bewildered. Arthur Wang, then at Viking Press and soon to found Hill and Wang, wrote to Hyman that he had discussed the story with friends for nearly an hour: “It’s damned good but I haven’t met anyone who is sure that they . . . know what it’s about.”

Only a few of the letter writers dared to hazard an interpretation. “In this story you show the perversion of democracy,” a reader from Missouri wrote confidently. “A symbol of how village gossip destroys a victim?” wondered a reader in Illinois. A producer at NBC believed it meant that “humanity is normally opposed to progress; instead, it clutches with tenacity to the customs and fetishes of its ancestors.” Some ventured wilder guesses. Marion Trout, of Lakewood, Ohio, suspected that the editorial staff had become “tools of Stalin.” “Is it a publicity stunt?” wrote a reader from New York, while others wondered if the printer had accidentally cut off a concluding paragraph. Other readers were simply confused by the plot—not everyone understood that Tessie was stoned to death. “The number of people who expected Mrs.

Hutchinson to win a Bendix washer at the end would amaze you,” Jackson commented wryly to Joseph Henry Jackson. Still others complained that the story had traumatized them so greatly that they had been unable to open the magazine since. “I read it while soaking in the tub . . . and was tempted to put my head underwater and end it all,” wrote a reader in St. Paul.

But the largest proportion of the respondents did admire the story, even if they did not understand it. “Only a true genius could have written ‘The Lottery’—a story that persists in staying in the thought of the reader, whatever interpretation may be reached, and compelling him to keep on wondering about it,” wrote a friend of Jackson’s parents. H. W. Herrington, who had been Jackson’s folklore professor at Syracuse, wrote that the story had disturbed his sleep as well as his waking thoughts, but that he had been “singing over it too as one must over a fine piece of art.” Jackson wrote back that the idea for the story had originated in his course, which may have been at least partially true, although she had read

The Golden Bough

before transferring to Syracuse.

Jackson and Hyman’s friends were mostly generous with their compliments. Herbert Weinstock, Hyman’s editor at Knopf, said it was “one of the most impressive stories

The New Yorker

has ever published.” Kenneth Burke judged it “a very profound conceit. . . . [T]he story starts the bells of possibility ringing.” Ralph Ellison, who spent Christmas with Jackson and Hyman that year, was more critical: he thought Jackson had “presented the rite in too archaic a form” and with too much understatement, though he was willing to admit that “it is a rich story and perhaps it succeeds precisely because of the incongruity to which I am objecting.” He also noted, approvingly, that he and Jackson were “beginning to work the same vein.”

Harold Ross, for his part, never went on the record with his opinion. But he wrote to Hyman in July that “The Lottery” was “certainly a great success from our standpoint. . . . Gluyas Williams [a

New Yorker

cartoonist] said it is the best American horror story. I don’t know whether it’s that or not, or quite what it is, but it was a terrifically effective thing, and will become a classic in some category.”

Jackson, though she was asked repeatedly, never would offer a

consistent explanation of “The Lottery.” Her friend Helen Feeley said Jackson told her that the story had to do with anti-Semitism. In fact, its theme is strikingly consonant with the French Holocaust survivor David Rousset’s book

L’Univers concentrationnaire

(1946), which argues that the concentration camps were organized according to a carefully planned system that relied on the willingness of prisoners to harm each other. The book was translated into English as

The Other Kingdom

in 1947 and was reviewed in

The New Yorker

, possibly by Hyman, who was a frequent contributor to the magazine’s section of brief, anonymous reviews.

Others have said that all the characters were based on actual people in North Bennington, and an early version of “Biography of a Story,” in which Jackson considers specific people in the village and how they would behave in such a situation, backs up this interpretation. She said something similar to Bennington professor Wallace Fowlie when he told her that critics had been explaining it in terms of ritual: “Shirley’s beautiful piercing eyes sparkled with an expression that was half surprise and half amusement. ‘The scene of that story is simply North Bennington. Just listen to the people here in town and the way they slaughter one another with words and stories and slander.’ ” Joanne Hyman, the toddler who was in the playpen while her mother wrote the story, says Jackson told her it drew from her first experience living in New England—the brief period she and Hyman spent in Winchester, New Hampshire—rather than their life in North Bennington. Sometimes she refused entirely to say what it meant: when Jennifer Feeley, Helen’s daughter, read the story in high school and asked Jackson about it, Jackson responded huffily, “If you can’t figure it out, I’m not going to tell you.”

Others have commented that “The Lottery” reflects a culture of casual violence common in Vermont at the time. Janna Malamud Smith writes that she was unprepared for the “rural harshness” that others took for granted; as a child, she was shocked to hear a friend of her parents’ talk casually about local factory employees torturing a mentally disabled coworker. Jackson depicts some of this harshness in “The Renegade,” written around the same time as “The Lottery,” in which Mrs. Walpole—another city woman who feels out of place in the country—is informed by a neighbor one morning that her dog has been killing

chickens. As she makes her way around the village doing her errands, everyone she meets has heard the rumor, and all kinds of gruesome solutions are offered: tying a dead chicken around the dog’s neck, letting a mother hen scratch out the dog’s eyes, or—most horribly—forcing the dog to run while wearing a spiked collar, so that it cuts off her head.

Still, Jackson almost certainly did not intend “The Lottery” as an insult to rural Vermonters, even if some of them read it that way. The best interpretation is likely the most general, something like what she wrote in response to Joseph Henry Jackson’s query: “I suppose I hoped, by setting a particularly brutal ancient rite in the present and in my own village, to shock the story’s readers with a graphic dramatization of the pointless violence and general inhumanity in their own lives.”

The New Yorker

’s Kip Orr, who was charged with the task of responding to all the letters on Jackson’s behalf, echoed this position in what became the magazine’s standard formulation. “It seems to us that Miss Jackson’s story can be interpreted in half a dozen different ways,” he wrote to reader after reader. “It’s just a fable . . . she has chosen a nameless little village to show, in microcosm, how the forces of belligerence, persecution, and vindictiveness are, in mankind, endless and traditional and that their targets are chosen without reason.”

In the summer of 1948, only three years after the end of World War II, the American public was still reeling from the horrifying scenes from the death camps of Europe, not to mention the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The term “Cold War” had been coined a year earlier in a speech by financier and elder statesman Bernard M. Baruch before the South Carolina House of Representatives, gaining currency after it was repeated by Walter Lippmann in the

New York Herald Tribune

. In the United States, Kip Orr’s “forces of belligerence, persecution, and vindictiveness” had recently assumed a new form in McCarthyism. The House Committee on Un-American Activities had already begun its infamous hearings regarding alleged Communist influence in the movie industry, and Hyman’s old friend Walter Bernstein was one of the screenwriters targeted. Soon Whittaker Chambers would expose Alger Hiss as a Communist operative within the U.S. government. When Arthur Miller’s play

The Crucible

—an allegory of the witch hunt

for Communists set against the background of the Salem witch trials—came to Broadway a few years later, a friend of Jackson’s commented to her on its similarity in theme. It is no wonder that the story’s first readers reacted so vehemently to this ugly glimpse of their own faces in the mirror, even if they did not understand exactly what they were seeing.

In Jackson’s story, the target of the lottery is indeed chosen at random, as Orr pointed out. But it seems hardly “without reason,” at least on the part of the author, that she happens to be both a wife and a mother. On the morning she wrote the story, Jackson was pregnant with her third child—a fact she omitted from “Biography of a Story”—and was occupied with taking care of her second; she had a break from the first for only a few hours. Published nearly a decade before Betty Friedan conducted the survey of Smith College graduates that would lead to

The Feminine Mystique

, the story depicts a world in which women, clad in “faded house dresses,” are defined entirely by their families. Though “The Lottery” has an anachronistic quality, with an atmosphere at once timeless and archaic, in fact it describes the world in which Jackson lived, the world of American women in the late 1940s, who were controlled by men in myriad ways large and small: financial, professional, sexual.