Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (37 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

Tessie Hutchinson, the lottery’s victim, in many ways resembles Jackson: her distraction, her self-consciousness about her housekeeping, her disheveled appearance. (Just as Tessie insists on finishing her dishes before she arrives at the lottery, Jackson carefully notes that she put away her groceries before sitting down to write the story.) Female sacrifice is a motif in “The Renegade” as well: the dog is named Lady, and the story ends with Mrs. Walpole metaphorically switching places with her, imagining the sharp points of the collar closing in on her own throat. If “The Lottery” can be read as a general comment on man’s inhumanity to man, on another level it works as a parable of the ways in which women are forced to sacrifice themselves: if not their lives, then their energy and their ambitions. The story is at once generic and utterly personal.

Jackson was less thrilled by the sudden recognition than she had expected to be. “One of the most terrifying aspects of publishing stories and books is the realization that they are going to be read, and read

by strangers,” she wrote later. “I had never fully realized this before, although I had of course in my imagination dwelt lovingly upon the thought of the millions and millions of people who were going to be uplifted and enriched and delighted by the stories I wrote. It had simply never occurred to me that these millions and millions of people might be so far from being uplifted that they would sit down and write me letters I was downright scared to open.” (In reality, the mail Jackson may have been most “scared to open” was more likely to be the invariably critical letters she received regularly from her mother.) Her tone is at least semijocular; she goes on to quote some of the more outrageous letters she received, including one from a convicted murderer and another from a group of “Exalted Rollers” who acclaim her as a prophet and ask when she will publish her next revelations. But her lecture broadcasts a level of anxiety about her fame that foreshadows the crippling agoraphobia of her later years—in which she feared going to the post office, among other things. “I am out of the lottery business for good,” she concludes.

At the end of “The Lottery,” as the villagers close in on Tessie, the slips of paper blow out of the black box and mingle with the stones on the ground. Like the letter used for blackmail in Poe’s “The Purloined Letter,” the platitudes Mrs. Hope sends out indiscriminately in “When Things Get Dark,” or the wicked little notes Mrs. Strangeworth leaves for her neighbors in “The Possibility of Evil,” they serve as reminders of all the ways in which the written word can wreak havoc.

IN A STROKE OF

particularly evil luck, the appearance of “The Lottery” coincided almost exactly with the publication of

The Armed Vision

, Hyman’s long gestating work of criticism. The title, which came from Coleridge’s

Biographia Literaria

, refers to the level of discernment attainable by the ideal critic: “The razor’s edge becomes a saw to the armed vision; and the delicious melodies of Purcell or Cimarosa might be disjointed stammerings to a hearer, whose partition of time should be a thousand times subtler than ours.” At more than 400 pages of tiny print, this impressive book was the apotheosis of the “scientific” approach to literary criticism that Hyman, guided by his dual

mentors—his Syracuse professor Leonard Brown and his critical idol Kenneth Burke—had been perfecting since college. In twelve densely argued chapters that began with a vicious takedown of Edmund Wilson, the

New Yorker

critic who was one of the dominant literary voices of the 1940s, and climaxed in an encomium to Burke (the book progressed from “villains to heroes,” as one reader noted), Hyman analyzed major contemporary critics as exemplars of different approaches: evaluative, Marxist, psychological, and so on. He argued the merits and faults of each in exhaustive detail, building to a conclusion in which he attempted to integrate the approaches in “the ideal critic.”

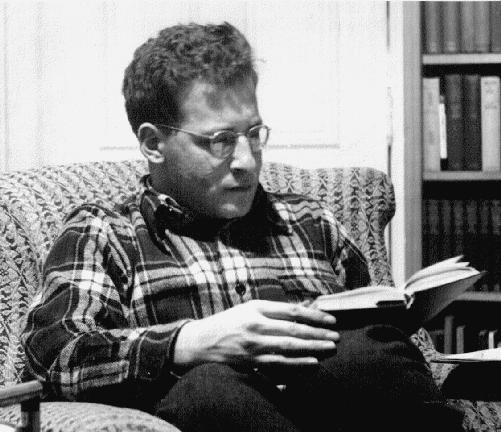

Hyman in 1947, while he was writing

The Armed Vision.

The Armed Vision

’s journey to publication was full of stumbles. Hyman found his dealings with Knopf so aggravating that he tried more than once to break his contract. His editors must have been no less annoyed by his conduct, which was, in truth, sometimes childishly obstinate. To begin with, he did not deliver the manuscript until April 1947—nearly two and a half years after the deadline. By that time, his original editor had left the firm, turning the book over to Herbert Weinstock, a scholar of classical music who would become an important writer on opera. On a personal level, Hyman and Weinstock got along well: Weinstock and his partner, Ben Meiselman, were among the Hymans’ houseguests in North Bennington. (Weinstock was among the very few relatively uncloseted gay men in New York publishing in the 1940s.) But professionally their relationship was rancorous.

Hyman’s desperate financial situation may have driven him to be more aggressive than usual with Knopf. Although he admitted it to almost no one, Bennington—which offered no tenure—had declined to renew his contract in the spring of 1946, after his first full year of teaching. His firing, for that was what it amounted to, was apparently more a referendum on his personality than on his teaching skills: the college president, Lewis Jones, found him abrasive. (Some of his colleagues believed him to be a victim of academic politics.) Upon his return, in September 1953, he would establish himself triumphantly as one of the superstars of the literature department. But for now he was out. “Stanley himself felt he had failed as a teacher,” says Phoebe Pettingell. After the book was finished, he planned to return full-time to

The New Yorker

—to write profiles, he hoped—and perhaps to New York City. But for the time being, he and Jackson decided to stay in North Bennington.

In some ways, Hyman’s firing was a boon: it meant more time to work on his already overdue book. On a practical level, however, he and Jackson were broke. Hyman’s weekly “allowance” (as he called it) from

The New Yorker

, cut from $50 to $35 that year, was nowhere near enough to support a family of four, not to mention his book-buying habit. Jackson’s story income was essential to their household, and after “The Lottery,” her greater earning power would be obvious. But in 1946, the year Hyman stopped teaching, she sold only one story: “Men with Their Big Shoes,” for which

The Yale Review

paid just $75. In 1947,

The New Yorker

declined to renew her first-reading option. Hyman was forced to ask both Jay Williams and Ben Zimmerman for loans. At least one trip to New York that year had to be canceled for lack of funds. Their situation began to improve in the spring of 1947, when Jackson signed her contract for

The Road Through the Wall

. Six months later she sold “The Daemon Lover” to

Woman’s Home Companion

for $850, and her fees would rise from then on. But for now, they needed money.

Since Hyman had taken most of his advance early, he was due only $150 when he finally delivered the full manuscript, in April 1947. At once he began agitating for more cash. When Weinstock enthused over the book, Hyman suggested that if he liked it so much, he might consider increasing the advance. That was not possible, so Hyman started

pressuring Weinstock to give him a contract for the next book, based on only an outline and a brief description. His idea was to study Darwin, Marx, Frazer, and Freud (“the greatest and most influential minds of the past century”) as literary writers, “on the theory that their great influence has been due, as much as anything, to their creative and imaginative powers.”

The Tangled Bank

, the book that eventually grew from this germ, would be a remarkable compendium of virtually everything Hyman had ever read or thought about. But Weinstock can hardly be blamed for not immediately seeing its potential.

Weinstock did not hold back in expressing his admiration for

The Armed Vision

: the book, he wrote to Hyman, was the most exciting manuscript to cross his desk in his three and a half years at Knopf, and he predicted it would become “what is loosely called a classic in its field.” The scholar William York Tindall, to whom Weinstock sent it for evaluation, largely agreed, beginning his report with the line “This is an important book.” But Weinstock worried—not unreasonably—about Hyman’s ability to complete the next project on time. He offered $1000 as an advance for the new book, then called

Four Poets

, to be paid whenever Hyman began work on it and thought he could complete it within a year.

Hyman wanted the money at once—a request that Weinstock found more appropriate for a banker than a publisher. It did not help that Hyman had yet to turn in his revisions on

The Armed Vision

. In a final desperate stab, Hyman prevailed upon

The New Yorker

’s treasurer to loan him $1000 with his future Knopf contract as a guarantee, provoking a stern rebuke from Alfred Knopf himself. “The basic point, it seems to me, is that you simply cannot, the book world being what it is—and who are we to set it right—count on getting . . . ‘money for rent and groceries’ from the kind of book you write,” the man who had once served squab to Hyman now scolded him. “It is a pleasure and a privilege to publish such books, but we cannot finance them as if they had sales possibilities which we are all but certain they have not.” A profile of Knopf that appeared in

The New Yorker

a little over a year later quoted him lamenting “the crassness of present-day literary men. ‘My God!’ he said last year, speaking of a writer who was asking for what he considered a premature and excessive advance. ‘This man tells me he

needs money to pay his grocery bills. What the devil do I care about his grocery bills?’ ” The writer, of course, was Hyman. The same profile notes that Knopf contracts were considered “a good deal longer, and a good deal more tiresome, than the contract of any other American publisher,” whch must have been slight consolation. The line about the groceries would be repeated in Knopf’s

New York Times

obituary, nearly forty years after Hyman’s request.

Insulted and furious, Hyman asked to be released from his contract, but Knopf wouldn’t even do that. “We will rest on our contract and hope that as time goes on you will think less badly of us than you no doubt do now,” he replied. (In the scrapbook in which he kept correspondence and reviews for

The Armed Vision

, Hyman taped below this letter the news report of Knopf’s skiing accident.) Jim Bishop, Hyman’s agent, told him there was nothing he could do—the Knopf editors liked the book and viewed it as “one of the prestige items of the year.” But “they don’t think it will sell worth a damn,” Bishop said, “and neither do I.”

In the end, Hyman backed down. But he was incensed a few months later to learn that the book’s price, owing to its long page count, had been set at $6.95—nearly $70 in today’s money—which he considered “criminal and farcical”: “It will make me a general laughing-stock and reviewers’ butt . . . [and] will kill absolutely any chance for a sale the book might have had.” (

The Road Through the Wall

, by comparison, sold for $2.75.) Since Hyman was depending on the book’s royalties to bring in some much needed income, this was not a trivial matter. He had hoped to earn more by selling off individual chapters to literary magazines, but their fees were as low as $25. The disparity between his income and Jackson’s rankled him. “You see our difference in scale,” he complained to Ellison.

This time Hyman had the contract on his side: it stipulated that the book’s price could be no higher than $5. “If Alfred A. Knopf Inc. . . . cannot fulfill in 1947 a contract that was made in 1943, Mr. Knopf should have accepted the chance I gave him in a letter some months ago to break the contract peaceably and let me go elsewhere,” he wrote gleefully, threatening to take up the matter with the Authors Guild. After a hasty consultation with the firm’s lawyer, Knopf conceded that

round to Hyman. But various altercations still lay ahead over the fees Hyman was charged for alterations, the index, and so on. By the time

The Armed Vision

was published, Hyman had racked up nearly $500 in additional charges on top of his $500 advance, all of which would have to be recouped against sales before he could start earning royalties.

Materially and emotionally, Jackson supported Hyman through these travails. The book was dedicated to her, “a critic of critics of critics,” and in the acknowledgments Hyman thanked her for doing “everything for me that one writer can conceivably do for another.” That may be a sly inside joke: Jackson and Hyman had publicly spread the rumor that Knopf owed his skiing accident to Jackson’s witchcraft. She had to wait for him to go skiing in Vermont, she said; federal laws prevented her from doing magic across state lines. (The joke would come back to embarrass her the following year, when, in the wake of her

Lottery

publicity, an interviewer asked her, quite in earnest, how she had broken Knopf’s leg.) Hyman’s files reveal that she read the manuscript carefully and made numerous notes. In a jocular “review” of the book that Hyman pasted into his scrapbook, she wrote that she had read it “perhaps more often, and with greater loving and painstaking care, than almost anyone else, excepting possibly mr hyman himself.” (The two writers made a game of coming up with fake blurbs and reviews of each other’s books, purportedly authored by Shakepeare, Samuel Richardson, and other idols.) Still, Hyman, always competitive, chafed at having lost out to Jackson in the race to publish their first books. “I am delighted that I have finally gone into type, since Shirley, who has already had page proofs on her opus, has practically stopped twitting me,” he wrote to Weinstock in the fall of 1947. And Jackson also used her joke review as an opportunity to slide in the dagger, noting that her qualifications for writing it were her “relations with mr hyman, which are of course about what you might expect, he having done everything for me that one writer could possibly do to another.” That slip at the end from “for” to “to” was surely intentional.