Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (34 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

The more reserved Farrar, who would be Jackson’s primary editor, came from a High Episcopalian Vermont family that was rich in pedigree but poor in cash: he attended Yale on a scholarship. In 1920, at age twenty-four, he became editor of

The Bookman

, a book review journal. Six years later, he cofounded the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, where Jackson would eventually serve on the faculty. His wife, Margaret Petherbridge Farrar, who joined him as an editor at Farrar, Straus, created the

New York Times

crossword puzzle in 1942. Straus was the commercial man, but Farrar was the firm’s literary backbone. In those early years, Kachka writes, “everything of quality was brought in by Farrar.”

From the outset, Farrar, Straus intended to be a literary house. “A new imprint on a book gathers character through the years,” announced the firm’s first catalog, in the fall of 1946. “Our list will be a general one. . . . We shall shun neither the realistic nor the romantic.” Farrar, Straus’s first literary success was Carlo Levi’s

Christ Stopped at Eboli

(1947). But the company was best known in its early years for a blatantly commercial diet manual by the bodybuilder Gayelord Hauser called

Look Younger, Live Longer

(1950), which sold about half a million copies and guaranteed the firm’s stability, at least for the time being.

When Jackson first met him, Farrar had “an owlish aspect,” with wire-rimmed glasses and red hair. He once described himself as having “no sense of humor and a vile temper,” but from the start Jackson’s relationship with both him and Margaret was warm and intimate. “I hope you will let me know whenever you feel like talking about the book, about any book, about anything,” Farrar wrote to her shortly after they first met. She and Margaret bonded over puzzles, which Jackson also enjoyed; for her part, Margaret found the book “so beautiful and so devastating, I can’t get it out of my mind.” John proposed changing the title to

The Innocents of Pepper Street

, but when Jackson balked, arguing that the wall was the book’s central symbol, he backed down. The copyediting was almost nonexistent; in return, she made not a single mark on the proofs. The book’s cover was dominated by the brick wall, with parallel rows of surreal lime-yellow trees extending eerily on either side.

The publisher’s standard request for biographical information flummoxed Jackson. Hyman ended up filling out the sheet for her. It paints an idiosyncratic picture:

She plays the guitar and sings five hundred folk songs . . . as well as playing the piano and the zither. She also paints, draws, embroiders, makes things out of seashells, plays chess, and takes care of the house and children, cooking, cleaning, laundry, etc. She believes no artist was ever ruined by housework (or helped by it either). She is an authority on witchcraft and magic, has a remarkable private library of works in English on the subject, and is perhaps the only contemporary writer who is a practicing amateur witch, specializing in small-scale black magic and fortune-telling with a Tarot deck. . . . She is passionately addicted to cats, and at the moment has six, all coal black. . . . She reads prodigiously, almost entirely fiction, and has just about exhausted the English novel. . . . Her favorite period is the eighteenth century, her favorite novelists are Fanny Burney, Samuel Richardson, and Jane Austen. She does not much like the sort of neurotic modern fiction she herself writes, the Joyce and Kafka schools, and in fact except for a few sports like Forster and [Sylvia

Townsend] Warner, does not really like any fiction since Thackeray. She wishes she could write things as leisurely and placid as Richardson’s, but doesn’t think she ever will. She likes to believe that this is the world’s fault, not her own.

Out of all this, only the detail about witchcraft remained in the final version—an obvious attempt at generating publicity. It looks out of place on

The Road Through the Wall

, the least spooky of all Jackson’s books. When the line appeared again on the

Lottery

collection the following year, reviewers took notice—not always in a way Jackson appreciated. But for now, it attracted little attention.

On November 13, 1947, Jackson and Hyman sat separately for the photographer Erich Hartmann. Hyman’s picture has a debonair quality—an image befitting the brash young author of

The Armed Vision

, which was scheduled at last for the following spring. His hair is closely cropped, and his expression is not exactly a smile, but something close. (In the version that was sent out with Hyman’s publicity materials, he wears a forbidding scowl.) Dressed in a dark wool jacket and patterned tie, he holds a smoldering cigarette that casts a plume of smoke toward his face. Jackson looks very young and very serious; she tilts her head slightly to the right, just as Hyman does, and her enigmatic half-smile is almost the mirror of his. Her hair is pulled back with a clip, and a string of chunky beads hangs around her neck. Behind her round glasses, her gaze is penetrating.

Jackson thought Hyman looked like “a man of distinction,” but she was disappointed in her own photos, one of which she thought resembled “Alexander Woollcott [a distinctively jowly

New Yorker

writer] imitating an owl.” She was being overly critical—the picture that became her standard publicity shot is an attractive one. Margaret Farrar found it “perfectly delightful and fetching.” But Jackson was always sensitive about her appearance. Throughout her life, she would consent to be photographed only with great reluctance, and eventually she refused entirely. Fifteen years after it was taken, that same photograph would appear on

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

.

The Road Through the Wall

was published on February 17, 1948:

“we hope [it] is a day you like,” Farrar’s assistant wrote to Jackson, with a nod to her superstitious tendencies. She dedicated it “To Stanley, a critic.” They both came to New York for the “ritual week,” which included a cocktail party in Jackson’s honor on publication day. At the time they were especially broke, and so anxious about the book’s potential sales that Hyman took it upon himself to complain to Straus about the firm’s publicity efforts. Straus, using all his sensitive social tentacles, sent back a soothing response in which he cautioned against too much optimism in the current “mediocre market” but assured Jackson and Hyman that the firm was making an “all-out effort.” “We believe in Shirley as a writer,” he promised. “We are all interested in the same thing—selling books—and we are all interested in the stature of Shirley as a writer now, tomorrow, ten years from tomorrow or twenty years from tomorrow.” Still, he allowed that reviews would be a crucial factor, and to reviewers a first-time novelist was “an unknown quantity.”

Stanley Hyman’s author photograph for

The Armed Vision,

taken by Erich Hartmann in November 1947

.

Alas, Straus’s cautions were validated. A few critics loved the novel: one recognized Jackson’s gift for diagnosing the “little secret

nastinesses” of the human condition, and another praised the “direct, unsentimental way” she wrote about children. But most were put off by the book’s negative depiction of humanity. “If you sometimes have bad days when you seem to remember all of the stupid, inane, embarrassing things that you ever did, then you will find a bit of yourself on every page, for Miss Jackson has selected only such incidents to carry her story, if indeed there is a story,” sniped one critic. Others found the ending contrived and melodramatic. Even

The New Yorker

could manage only a backhanded compliment: Jackson’s “supple and resourceful” style managed to make her “shopworn material appear much fresher than it is.” Some friends were also less than enthusiastic: Jeanou, to whom Jackson proudly sent a copy of the novel, loved the descriptions of suburban life but was disappointed in the ending, which she found melodramatic. The reaction of Geraldine and Leslie, who had recently moved back to the Burlingame area, has not survived, but it could not have been positive. Early sales were disappointing—only around 2000 copies. Straus had projected 3500, the minimum necessary for Jackson to earn back her advance. In response, Farrar, Straus decided to delay her book of stories until the following year.

Jackson, it seems, was not overly disheartened by the reaction. At any rate, it hardly discouraged her from using fiction to tell her readers—or her neighbors—unpleasant truths about themselves. And with this first investigation of a small town in which neighbors gradually undo one another, she laid the groundwork for the thunderbolt that would come next.

8.

“THE LOTTERY,”

1948

The morning of June 27th was clear and sunny, with the fresh warmth of a full-summer day; the flowers were blossoming profusely and the grass was richly green.

—“The Lottery”

“

T

HE LOTTERY” IS A KIND OF MYTH; AND OVER THE YEARS

, various myths have been told about its writing. Jackson’s neighbors in North Bennington would say that she had been inspired to write it after village children had thrown stones at her while she was out for a walk with her baby. In one version of the lecture she often gave about “The Lottery” and its aftermath, Jackson said a book she had been reading about “choosing a victim for a sacrifice” had led her to the idea. At the time she wrote the story, Hyman and Jay Williams were collaborating on a proposal for an anthology of myth and ritual criticism, for which Hyman had begun to collect numerous books, one of which might well be the one she refers to. Jackson’s interest in myth and ritual dates back to her collegiate reading of

The Golden Bough

, anthropologist Sir James

Frazer’s compendium of ancient rites and customs. Frazer’s main area of interest is the rituals surrounding the death and rebirth of a vegetation god, a fertility rite that is relevant to “The Lottery”; he also describes the use of scapegoats, another of the story’s themes.

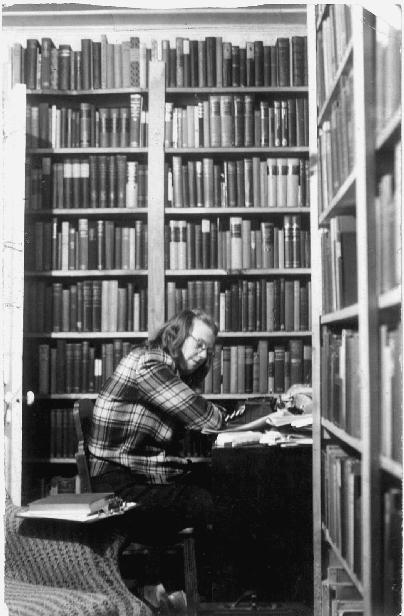

Shirley Jackson in her study, late 1940s.

The most enduring myth, however, was created by Jackson herself, in the version of her “Lottery” lecture that was published after her death as “Biography of a Story.” As she told it, she was out doing errands one bright June morning “when summer seemed to have come at last, with blue skies and warm sun and no heavenly signs to warn me that my morning’s work was anything but just another story.” She was pushing Joanne, around two and a half, in a stroller; Laurence was

at kindergarten. The idea came to her, she said, on the way home—“perhaps the effort of that last fifty yards up the hill put an edge to the story”—and as soon as they arrived, she put Joanne in her playpen, put away the groceries, and sat down to write. She was finished by the time Laurence arrived home for lunch. “I found that it went quickly and easily, moving from beginning to end without pause,” she would recall. “As a matter of fact, when I read it over later I decided that except for one or two minor corrections, it needed no changes, and the story I finally typed up and sent off to my agent the next day was almost word for word the original draft.”

As with some of the other stories Jackson told about her life, this one takes some liberties with the factual record. For one thing, she puts the story’s date of composition as sometime during the first week of June, three weeks before its publication in the

New Yorker

of June 26, 1948, which would have meant an unusually quick turnaround from manuscript to print. A note in Jackson’s handwriting on the draft of “The Lottery” in her archive indicates that she submitted it to MCA on March 16, 1948. Jim Bishop had recently left the agency, and another agent, Eleanor Kennedy, was now handling Jackson’s submissions. Kennedy wrote to Jackson on April 6 that Gus Lobrano liked the story but had “some reservations about it” and would send on a detailed critique: “He

assured me that if you can put it in proper shape for them, they will take it,” she wrote. Jackson submitted the revised story on April 12. On April 26, she received a telegram from Kennedy. Lobrano had bought “The Lottery” for $675—about three times what he had paid for any of Jackson’s previous stories.