Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (15 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

Many of the male students, including Stanley, lived in the fraternity houses that lined the surrounding blocks: his was Sigma Alpha Mu, one of the few open to Jews. Campus social life centered on the Greek system and sports: the campus was anchored by Archbold Stadium, whose castlelike entryway featured turrets framing a gateway arch. But there were also numerous options for the literarily inclined, including the

Syracusan

literary and humor magazine, where Shirley would publish some of her first stories, and the

Daily Orange

newspaper, where Stanley was a writer and editor. The Cosmo, an all-night coffee shop known as “the Greeks,” was a favorite student hangout.

Shirley was never a top student and would graduate without distinction, but her college notebooks demonstrate her roving intellect:

in addition to her major in English, she took courses in linguistics, geology, and criminology. She developed a fondness for Thomas Hardy and Joseph Conrad, as well as a brief affection for the Victorian poets Algernon Charles Swinburne and Ernest Dowson. Professor H. W. Herrington’s course in folklore was another influence she would later acknowledge. “I am going to write my paper for this course on superstition—the need for it, the use of it, its manipulations, its use in literature, [its] effect on writers,” the future author of “The Lottery” recorded in one of her college notebooks.

Switching colleges was a social challenge for Shirley not unlike her transfer to Brighton High School. She initially felt so isolated and anxious that for three days she kept her bags packed, so that she could leave at any moment. “it seemed that everyone was completely at ease and surrounded by friends but me,” she later recalled. Like Natalie in

Hangsaman

, she initially left her room only for meals. Her primary pastimes were solitary: she spent hours in the record-listening room playing

Caucasian Sketches

and Prokofiev’s brooding

Lieutenant Kije

. She exchanged frequent letters with Michael Palmer, the boy she had been dating in Rochester, and also with Jeanou, now a committed Communist after encountering veterans of the Spanish Civil War in Paris—she asked Shirley to send her copies of the

Daily Worker

. A story Shirley wrote around this time describes two roommates: one a transfer student named Mary who knows no one, the other a popular girl who makes little effort to help her roommate adjust. At the end of the story, Mary—who has boasted that she has “a boy back home”—fakes a love note on a photograph of a man that she puts on display. In an alternate draft, the roommate goes out with friends while Mary hides in their room, writing letters to her mother. She throws away three drafts describing her loneliness before she is able to manufacture the desired cheery tone. The first version says plainly, “Dear Mother, I want to come home.”

Within a few months, however, Shirley came into her own socially, thanks to the creative writing class she was taking. The professor, A. E. Johnson, was a poet whose own work tended toward the florid;

mercifully, she did not absorb his style. But another student in the class became a close friend. Seymour Goldberg was a talented artist from Crown Heights, Brooklyn, who had already established himself in business as an interior decorator. Determined to seek out whatever adventure there was to find in the sleepy upstate town, they would head out together to explore a designated destination—a bar, a department store, the swanky Yates Hotel downtown—then return to campus to write about what they had seen. “I have . . . seldom, if ever, been as completely happy,” Shirley wrote in December. “I have been relaxing into myself. I do not feel the constant strain to be someone else.” Since arriving at Syracuse, she noted with satisfaction, she had succumbed to “hysterics” only once. Perhaps the dramatic highs and lows of the last few years were behind her. “I am going to catch the world in my hand,” she enthused.

As always, Shirley’s writing was the element of her life that brought her the greatest personal satisfaction. Now, for the first time, her peers were starting to acknowledge her talent. She carried her notebook everywhere and briefly began smoking a pipe before taking up the Pall Mall cigarettes that would be her lifelong habit. “People are beginning to grow accustomed to Jackson sprawled in a corner, scribbling away in her eternal notebook,” she told her Rochester friend Elizabeth Young, whom she had nicknamed Y—pronounced “ee,” to rhyme with “Lee,” Shirley’s new nickname for herself. “I have become a mad Bohemian who curls up in corners with a pencil.” She tantalized Michael Palmer by telling him about the “epochal novel” she was working on, but refused to let him see it.

She also had a new suitor: Alfred Parsell, a senior in the creative writing class. A story he wrote demonstrates just how different she was from the typical Syracuse coed. “He knew [his roommates] didn’t like her, that they thought she was crazy, and that they thought he was crazy because he went out with her,” the unnamed narrator says. “He could never make them see beyond her impetuous, high-strung mannerisms and her seemingly fantastic ideas and actions.” The speaker’s friends are openly malicious, telling him to stand the girl up or tell her he broke

his leg—anything to avoid going out with her. But the end of the piece finds the narrator and his beloved walking joyfully in the rain, “singing and shouting at the tops of their voices, splashing through puddles, dodging automobiles, and getting wetter and happier all the time.” In reality, gentle, kindhearted Al was never able to make any headway with Shirley, who found him too dependable for her taste.

Jackson’s successful first term at Syracuse culminated with the appearance of

The Threshold

, the class magazine produced by Johnson and his students. Published in February 1938, it quickly made the rounds of the college. “Surprisingly enough, it’s good,” Shirley wrote to Y. “I can write now, more fluently and better than ever before.” Al Parsell had written a story called “The Good Samaritans,” a turgid piece about a writer who breaks down on a book tour, unable to bear the hypocrisy of his audience. Seymour Goldberg’s contribution, “Of Lydia,” was a charming character sketch of an eccentric Russian woman who shares a few characteristics—notably a love of pomegranates—with Shirley, whom he liked to call by Russian nicknames. Perhaps he was a little bit in love with her, too.

“Janice,” Jackson’s story, opened the magazine. Barely 250 words, each one chills. There is no plot: a girl, chatting with her friends, casually mentions that she happens to have attempted suicide. Written entirely in dialogue form, with the arresting refrain “Darn near killed myself this afternoon,” the story precociously displays Jackson’s signature talent for combining the horrific with the mundane. Janice’s conversational bomb, dropped ever so gently, shatters the placid surface of cocktail-party chitchat to reveal a hidden darkness. Jackson apparently based the main character, at least partially, on a girl she had known in Rochester; she didn’t even bother changing the name. (After Y showed the real Janice a copy of the story, she refused to speak to Shirley again.) But Jackson likely chose to tell Janice’s story in part because it contained elements of her own experience.

The Threshold

, not surprisingly, found its way into the hands of sophomore Stanley Edgar Hyman, a dual English and journalism major. The preface alone must have gotten him sharpening his critical knife: it attacked the intellectual limitations of proletarian writers and their

“specious scientific conditioning whereby the magic and the miraculous are banished and the body is gelded of its very soul.” The budding literary critic scoffed at most of what he read. But “Janice” brought him up short. Stanley closed the magazine demanding to know who Shirley Jackson was. He had decided, he said, to marry her.

“

YOU WERE THE ONLY

live thing I had seen outside the greenhouse all winter,” Stanley told Shirley after their first meeting, which took place on March 3, 1938, in the library listening room—Shirley’s favorite spot on campus. The skinny, bespectacled, curly-haired Jewish intellectual from Brooklyn and the tall, redheaded, golf-playing California girl must have seemed an incongruous pair. But in many ways, their interests were perfectly aligned, as they always would be. From the first days of their relationship, Stanley took pride in Shirley as his personal discovery. He was her faithful cheerleader, encouraging her to write more and to write better; he also saw himself in the role of her educator, constantly suggesting books for her to read. Though he was entirely

convinced of her genius, he saw it as innate, instinctive, and perhaps even unrecognized by her. He told Walter Bernstein that she had “no idea what the things she wrote meant. Whatever came out of her head, she put on the page,” Walter recalls.

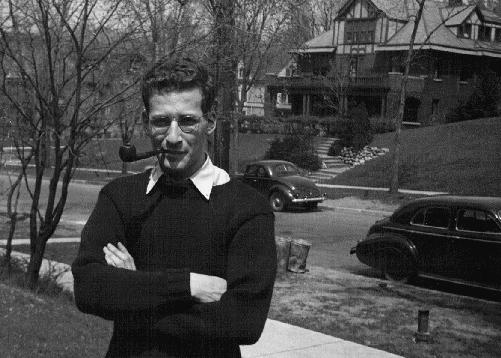

Stanley Hyman outside his fraternity house in Syracuse, late 1930s.

Stanley had hoped to write fiction himself, but once he met Shirley, he realized that he could not compete. Stanley “wrote painfully, it was a tedious, forced thing, whereas she—the thing flowed like you turned on a faucet,” said June Mirken, Stanley’s old friend from elementary school, who graduated a year behind him and Shirley at Syracuse. “He talked a lot but she wrote better,” another of their college acquaintances recalled. Instead, he would be the cool-headed intellectual who helped Shirley realize her full creative powers and then interpreted her work to the world: a perfect symbiosis. Between them, the criticism flowed largely in one direction. Shirley would comment on Stanley’s writings, but she rarely worked them over with the same gusto he brought to hers. Throughout their marriage, he gave her detailed pages of notes on all of her novels and many of her stories. She would dedicate

The Road Through the Wall

, her first novel, to “Stanley, a critic.” It became their custom to present each other with leather-bound editions of their own works, inscribed “To S with love from S.”

Shirley, in contrast to her suitor, was not immediately convinced that she would marry Stanley. Age was one issue: both were sophomores, but she was two and a half years older, and she worried about his immaturity. (Starting with their marriage license, she took to reporting her birth year as 1919 rather than 1916 to disguise their age difference, an error that was repeated for years in the biographical and critical literature about her.) Religion was another. Shirley was untroubled by Stanley’s Jewishness, but a number of her acquaintances, reflecting the disdain for mixed marriages then pervasive, expressed surprise that she would date him. Though Syracuse was less conservative than the University of Rochester, mixing religions (and even more so races, which was illegal in most states) was nonetheless frowned upon.

Primarily on religious grounds, Shirley’s parents expressed strong opposition to the relationship, which they discovered over the summer, when a flurry of letters from Stanley made it impossible to

conceal. Geraldine, who found out first, did not approve of her daughter’s dating a Jew, but also did not forbid Shirley to continue the relationship—perhaps hoping, as parents often do, that it would quietly fade away. Geraldine did, however, suggest that Leslie, whom Stanley nicknamed “Stonewall,” should not be told. The secret inevitably came out when Stanley showed up in Rochester for an impromptu visit. The couple were sitting together on the front porch when Shirley’s parents drove up: she had thought they were out of town, but Leslie and Geraldine changed their plans without telling her. Unwilling to confront Leslie, Stanley leaped over the railing and ran off. Shirley had no choice but to go after him, all the while dreading the scene that would eventually ensue at home. Stanley later tried to explain that he was self-conscious because he hadn’t shaved; he didn’t want to meet her father for the first time “looking enough of a bum to confirm his worst suspicions.” But Shirley was furious at his rudeness. Geraldine had raised her with certain standards of behavior: you don’t turn tail and run at the sight of your girlfriend’s parents, no matter how badly you might need to shave.

Her doubts notwithstanding, Shirley quickly recognized Stanley as the intellectual partner for whom she had been waiting all her life: attractive (if not conventionally handsome), sexual, funny, and fearfully brilliant. “Your intellect is a half-crazed centaur,” she wrote in a poem addressed to him. In

Hangsaman

, Natalie muses that “no one can really love a person who is not superior in every way.” For the first time, Shirley had found a man whose intellect she could truly admire.

Shirley shared with Stanley her obsessions with Villon and the commedia dell’arte, as well as new favorites Swinburne and Dowson. She adopted his all-lowercase typing style—Stanley had recently given up the shift key, likely under the influence of E. E. Cummings, whose poetry he had read so many times he knew much of it by heart—and would continue to type drafts and informal letters in lowercase for the rest of her life. They wrote each other notes in code, using Hebrew letters to spell out English words. And she started making humorous drawings to share with him, depicting herself with a cartoon character that is a cross between a penguin and an eagle: a squat figure with giant feet,

a large beak, and a perpetual scowl. (They sometimes called it Boid-Schmoid.) The Shirley figure is much taller, with wavy hair sticking out from her head in every direction. In one, Shirley bends down toward the bird, who points his beak at her. The caption reads: “He wants to know why no one ever kisses him passionately.”