Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (16 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

They were a perfect pairing: writer and critic, gentile and Jew, S and S. Perhaps they completed each other too well. Natalie, in the throes of her delusion, imagines that a person could be destroyed by a “single antagonist . . . who was calculated to be strong in exactly the right points.” For Shirley, that antagonist was Stanley. Their symbiosis was always in danger of turning parasitic. “Stanley left me tonight with a powerful feeling of anticlimax, determined never to see me again,” Shirley wrote in her diary on March 22, 1938, after the two of them had spent four hours together in nearby Thornden Park. She was certain he would reappear to take her out the following week. In fact, he held out for nearly two weeks before calling her again. It wasn’t from lack of interest: he was alarmed by the violence of his feelings for her. “all along i had been so dazed by you that i couldn’t see you more than once a week and keep my sanity,” he admitted later. He went home for the Easter break determined to get a grip on himself, resume his normal routine, and cut Shirley out of his life “like a cancer.” Instead, he “came back, made straight for lima cottage, and stayed there until the summer began.”

At first, it was Shirley who set the terms. She bragged to Stanley that she could make him do anything she wished, and he did not deny it. “He is absolutely where I wanted,” she gloated after one of those early nights together. “I am proud, and completely powerful.” When things were good between them, Shirley was the happiest she had ever been. In May she began a story with the lines, “I leaned my head back against Stan’s shoulders and relaxed. I was at peace.” From early on, she took on the role of his caretaker: a note to herself includes reminders to “give Stan time to read,” “make him go to YCL meetings,” “see that he gets some sleep,” and “make him laugh tonight.” Yet she worried about how their balance of power could change. The idea of falling in love with Stanley frightened her: “he could break me mentally if he chose.”

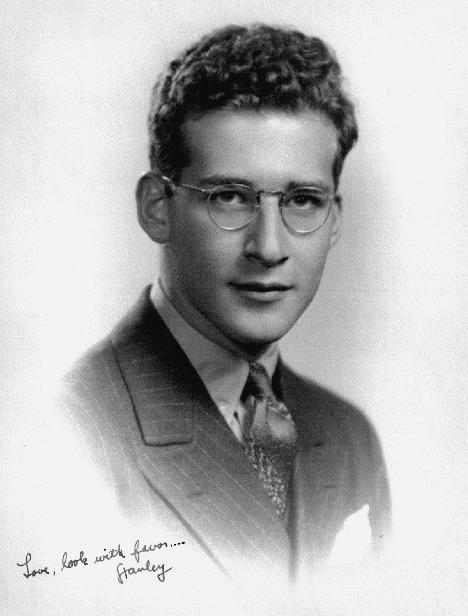

Stanley inscribed his yearbook photographs to Shirley with romantic quotations.

For all his ardor—“Did I remember yet today to tell you that I love you?” he would ask her daily—Stanley could be cold and inattentive. “I must beg him to come, tease him and argue with him to begrudge me—and so condescendingly!—ten minutes of his time,” Shirley complained to Jeanou. He was opinionated, bossy, and dismissive of Shirley’s taste in literature, preferring the modernists to the nineteenth-century writers she adored. And he turned the full force of his critical acumen on her, belittling her pitilessly, just as her mother had. In one of Shirley’s notebooks, he corrected her use of the abbreviation “cf.” in a memo—to herself. A draft of one of her college poems displays his merciless annotations, culminating in “Marx knows [Stanley’s substitute for “God knows”] you ain’t no poet.” When they disagreed politically, he insulted her by calling her a debutante. If he had not yet mastered the art of the literary takedown, his verbal arrows already showed expert aim: how that word must have stung.

Stanley’s communism was an initial source of dispute. Politics interested Shirley “less than does sanskrit”—presumably the most boring thing she could think of. She attended a few meetings of the YCL to please him, but she never joined the Party. As a writer who was already developing a very different style, Shirley found Stanley’s views on proletarian literature anathema. At Rochester, she had heard the writer Burton Holmes speak about his travels in the Soviet Union and was appalled by his reports of Stalin’s repression of religion and art. “I think any nation which can do to Beauty what they have done must be a race of idiots,” she wrote afterward. Where Stanley admired the gritty realism of John Steinbeck and John Dos Passos, she preferred the more esoteric high modernism of Djuna Barnes: both the early novel

Ryder

(1928), written in a bawdy mock-Elizabethan style, and the better-known

Nightwood

(1936), a dreamlike chronicle of a lesbian love affair in 1920s Paris.

During their first summer apart, Shirley briefly declared her allegiance to the Party and began reading the

Daily Worker

, probably just to annoy her conservative father. Her pose fell apart at once. Why, she wondered in a letter to Stanley, must she be branded a capitalist oppressor simply for neglecting to declare herself on the side of revolution? Couldn’t she be politically neutral? His response, in a letter that ran to fifteen pages, was harsh. No one could be neutral in the class struggle, he told her. More important, as a writer, with a heightened sensitivity to injustice, misery, war, poverty, and other social problems, she had an even greater obligation to “portray life, to write true. if the major feature of life today is misery and starvation, you must show misery and starvation.” Art that failed to do so would ultimately fade away: “it cannot meet the inflexible criterion of literary worth, ‘is this thing true? is this the way things were?’ ” Hurtfully, he lumped her story “Janice”—which she had thought he admired—among the failures, calling it “a finger exercise, well done, but meaningless.” He had praised it, he said, because it showed “a style graphic and economical enough to say something and say it well someday.” Perhaps in an attempt to be conciliatory, he allowed that her blinkered perspective wasn’t her fault; it stemmed directly from her upbringing. “when

you add knowledge to [your sensitivity], and not only feel evil but understand it, you will almost certainly be a great writer.” Eventually Stanley would abandon these inflexible standards and acknowledge that literature had a meaning and a purpose beyond the political. But in his youthful zeal, he was unable to look past ideology.

More problematic was Stanley’s persistent interest in other women, which he saw no reason to hide. Dowson’s poem about a man who confesses infidelity even as he pines for his lost love—“I have been faithful to thee, Cynara, in my fashion!”—became their personal shorthand. (“My fashion has been acting up again,” Stanley would sometimes say, addressing Shirley as “Cynara,” after he had been out with another woman.) As much as he loved Shirley—and he was already deeply in love with her—Stanley, embracing a self-styled polyamorous philosophy, saw no reason to limit himself to a single woman. He believed he held the moral high ground: open marriage was a Communist principle. His hero John Reed—Stanley recommended

Ten Days That Shook the World

, Reed’s eyewitness account of the Russian Revolution, to anyone who would listen—was notorious for his affairs. Shirley, too, was welcome to go out with whomever she liked, he asserted rather disingenuously. She would take him up on it only once.

Stanley’s dalliances with other women left Shirley profoundly unsettled. “I’ll do anything you want, only don’t leave me alone without you anymore,” she implored him in an unsent letter that spring. One particularly upsetting incident involved Florence Shapiro, the art student from Queens whom Stanley had met through the YCL. Stanley, neglecting to mention he had a new girlfriend, invited Florence to his room one night. “He kept making remarks indicating that he liked my figure,” Florence recalls. Then Shirley walked in. After that, Shirley never let Florence forget that she was in charge. “She didn’t like me and she let me know it,” Florence remembers more than seventy years later. The new couple had scenes in which Shirley would cry and throw Stanley out, then telephone his fraternity house over and over, worried that he had caught pneumonia outside in the cold. Later she would berate herself for her cruelty to him. “Stanley, crawling, is still powerful,” she admitted soon after they met.

THE RELATIONSHIP BECAME

more contentious over the summer of 1938. Instead of visiting Jeanou in Paris for Bastille Day, as the two friends had once planned—a trip that, even if the Jacksons had allowed it, the imminent outbreak of war now made virtually impossible—Shirley returned home to Rochester to resume her long-standing routine of golf, dinner at the country club, and exploring the city’s cafés and secondhand bookstores with Elizabeth Young. Stanley enjoyed his usual freedom, first crashing with Walter Bernstein at Dartmouth and then heading to New York for his brother’s bar mitzvah before starting his $20-a-week blue-collar job at the paper mill in Erving, Massachusetts. This endeavor was met with skepticism: the workers at his father’s paper business, as well as the barbers at the local barbershop where Stanley had been getting his hair cut since childhood, all predicted that he would not last two weeks at manual labor. “they will eat those words like radishes,” he vowed. In fact, he made it through nearly two months.

While apart, Shirley and Stanley wrote to each other addictively, sometimes twice in a day. Never published, the letters are thrilling to read: witty, furious, and often brilliant. Shirley’s warmth and humor bubble up from her pages. As a teenager, she had developed her voice in correspondence with an imaginary boyfriend; now, at last, her correspondent was flesh and blood—and did not hesitate to remind her of his corporeality. “for god’s sake can you think of any telepathic way by which i can get myself into your arms and stay there?” she wrote in early June. Stanley responded no less effusively: “i ought to stop wasting typewriter ink in letters, rush to rochester, and grab you in my arms, which is what i want to do more than anything in the world.”

Stanley filled his letters with gossip about mutual friends, humorous anecdotes, and commentary on his reading, which proceeded at a frenetic pace. In a single week he mentions plays by Archibald MacLeish; fiction by Jean Toomer, William Saroyan (“every once in awhile the goddamned armenian writes a marvelous story, buried in all that trash”), James Gould Cozzens, and

New Yorker

art critic Robert Coates; literary theory by Yvor Winters; and, for a break, James Thurber’s humor. He

had moments of tenderness: during a rare phone call, when he heard Shirley’s voice for the first time in two weeks, he wept. But his written register tended to the brash and bawdy. He addressed Shirley by inventive, sometimes vulgar pet names (“darling slut”) and was forthright about his physical longing for her. Just to look at one of her letters, he avowed, gave him an erection. He repeatedly begged her to send him a lock of her pubic hair. And he berated her for any perceived indifference, especially if she failed to write back promptly enough.

Stanley’s love for Shirley, however, did not prevent him from pursuing other women, especially when he was drinking. At his brother’s bar mitzvah, he drank an entire quart of scotch, sneaked out with two more bottles in his pockets, and ended up at the apartment of three female acquaintances living a life of “genuine bohemia,” with people sitting all over the floor, the corners littered with empty liquor bottles, and the walls hung with bad oil paintings, generally nudes, made by friends. The girls who lived there lay around “in various stages of undress,” he reported, idly swatting at the bedbugs and cockroaches. Stanley retained enough of his bourgeois upbringing to be disgusted by the filth, but he found the girls alluring. “i fondled them all indiscriminately [and] called all three of them ‘baby.’ ” He might well have slept with one or more of them, but for the fact that he was “so drunk that i couldn’t get a hard on to save my life.” Also, he was afraid of the bedbugs.

Shirley refrained from commenting on this episode, but Stanley continued to detail his escapades in a manner that even a woman less sensitive and devoted might have found distressing. “i promised you a précis of the female situation here,” he wrote from Erving, describing four girls in the factory who had caught his eye. One, “a polish slut of twenty-six,” was “damned good-looking in a consumptive way”; another was a “buxom creature” who drove Stanley into “fearful erections” every time he worked opposite her, until he discovered that she was a “mental defective.” Describing a weekend spent with his family at a Borscht Belt hotel (“typical jewish middle-class summer resort, fabulously expensive, excessively somnolent”), he related a tale about an abortive attempt at seduction that might have sparked guffaws from Walter Bernstein but understandably failed to amuse his possessive girlfriend:

i also made a play for two girls that i had seen together all that day, getting them apart and telling them practically the same thing. i was coming along pretty well with the older one when i began to feel lousy and went to bed (be it forever to my credit that when she said what, not leaving so early? why the evening is young, i said yes, too young for me). the next day the two girls drove home with us. naturally, as i could have expected, they were mother and daughter.

Stanley sometimes tried to soothe Shirley’s feelings after these dalliances. “you have forever spoiled me for other girls,” he told her after one episode. But he truly seems to have felt obliged to be transparent about both his beliefs and his activities: he regarded monogamy as a politically and philosophically useless enterprise, and he saw no reason to restrict himself. The obvious argument—that Shirley wanted him to—did not compel him in the least.

Stanley’s insistence on his own moral rectitude was particularly hard for Shirley to handle. She tried her best to take his escapades as casually as he seemed to, but—to her shame—each one made her “all sick inside.” “if it turns you queasy you are a fool,” he responded unsympathetically. Rather cruelly, he made it clear that both her jealousy and her conventional insistence upon monogamy were repellent to him. “it was a copulation, simply that and nothing more,” he scolded her when she ventured to complain about his sleeping around. Casual sex was one thing; his love for her was entirely separate. Indeed, he was capable of declaring his love in the most romantic terms in the very same letters that detailed his infidelities.