Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (20 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

But

Spectre

’s primary political cause was discrimination against blacks, which was then just beginning to become a major social issue, especially among Jews. (Apart from June Mirken’s story in the first issue, the magazine was silent on the subject of anti-Semitism at Syracuse.) Black students could be admitted to Syracuse but were forbidden to live on campus. At the same time, Marian Anderson, the African-American

singer whose operatic voice electrified audiences in the late 1930s, had become a cause célèbre when the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow her to perform before an integrated audience in Washington, D.C.’s Constitution Hall. Anderson “sells out every time she comes here, but they won’t allow negro girls in the college dormitories,” the editors protested in the third issue. “Maybe it’s all right if you’re no closer than the sixth row.” After interviewing various Syracuse administrators, they wrote, they had been unable to determine why so few black students were admitted to the university. The primary argument—that there was no place on campus for blacks to live—was prima facie ridiculous: “The overwhelming majority of white students on campus have no slightest objection to living with negro students, and would be pretty stupid and bigoted if they did.” But the editorial ended on a note of optimism about the future: the NAACP had recently started a branch on campus. “We wish them all the luck in the world.”

Most of what

Spectre

published was typical college literary magazine fare, but a few items stand out. “Big Brown Woman,” an appreciation of Bessie Smith by Stanley, reveals his growing range as a critic. Stanley had recently developed a serious interest in jazz and blues, and whenever he was in New York, he visited the nightclubs as often as he could afford to. One of his favorite hangouts was Nick’s in Greenwich Village, which held Sunday jam sessions featuring musicians such as Sidney Bechet, Muggsy Spanier, and Jelly Roll Morton, with famous bandleaders Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, and others making occasional appearances. Stanley especially favored Nick’s because the club declined to enforce the usual two-drink minimum; you could listen all night for the relatively low cover of seventy-five cents. Watching these musicians play, Stanley had an epiphany: popular culture was just as appropriate a subject for criticism as highbrow art. In his writing about blues music, which would remain a lifelong area of fascination, he took on a new tone: warm, enthusiastic, sincere.

At the time, recordings by African-American artists, primarily blues and gospel, were known as “race records.” Under a segregated system, the recordings were produced by white-owned record companies and marketed to African-American consumers; white collectors of

black music were highly unusual. Alta Williams, the Jackson family’s black maid, helped Stanley acquire many of his Bessie Smith records. His observations about them were acute. On the recording of “Trombone Cholly,” with Charlie Green, “Bessie talks to that trombone and it stands up and talks back to her.” When Louis Armstrong “picked up a phrase or a bar and . . . turned it back on her and sent it up and up and up, clear and round, it was like Bessie singing a duet with herself.” And when she sang, he wrote,

She would rest her bare bronze arms easily at her side, open her well-rouged lips until you could see all of the big white teeth, half close her eyes, and start to sway. . . . Then she would lean forward and let her big full voice roll out over the house. . . . There was nothing you could do about it except sit back and listen and let the sound pour over you like a heavy surf.

Spectre

also marked the only time Shirley published poetry under her own name. Three of her poems appeared in the second issue: “Letter to a Soldier” as well as “Black Woman’s Story,” spoken in the voice of a woman whose husband is lynched, and “Man Talks,” about a worker on the skids. Each was a sonnet in traditional form, but the magazine printed them as prose poems, in paragraphs, so that the reader must do the work of discerning the hidden sonnet. The effect is a little obscurantist: Why go to such effort to disguise a poem? Just as she couldn’t break prose into short lines and call it free verse (as Stanley had once lectured her), Shirley also couldn’t put a poem into paragraph form and call it prose.

The fourth issue was

Spectre

’s last. The cause of its demise was said to be Shirley and Stanley’s joint review of three new poetry books: two by Syracuse students and one by her former professor A. E. Johnson. They signed the piece with their initials—hardly a disguise, especially considering that they published many pieces under pseudonyms, including poems and stories by Shirley writing as St. Agatha Ives and Meade Lux (the latter pseudonym an homage to the boogie-woogie pianist Meade Lux Lewis). They went easy on the younger poets, but singled

out Johnson as “advocat[ing] retreat and weakness. . . . Professor Johnson is hidden away from the world, and happy in his illusion.” Considering what Stanley, who had been practicing the art of the takedown since high school, was capable of, the criticism was not that harsh; but it was apparently the last straw for the Syracuse administration. Commencement 1940 would be the end of

Spectre

, although that fall June Mirken was able to resurrect its spirit in a new, longer-lived magazine called

Tabard

. The relative mildness of the review raises the suspicion that the administration’s displeasure might have had more to do with

Spectre

’s polemics about racial discrimination at Syracuse than with the editors’ opinion of an English professor’s poetry. “The college was glad to be rid of both us and the magazine,” Stanley wrote later with pride.

Meanwhile, Shirley and Stanley were trying to settle on their plans for after college. Stanley’s hopes of publishing the poetry textbook he had written the previous summer had come to nothing. Despite Brown’s encouragement, the educational publisher Scott Foresman had rejected the book, and Stanley shelved the project. Walter Bernstein had already published two stories in

The New Yorker

—“most of which I wrote,” Stanley reported glumly of one of them—and spent two weeks working there as a reporter in the summer before their senior year, of which Stanley was hardly able to conceal his jealousy. And if Shirley’s father had ever been serious about sending her to Columbia’s graduate writing program, that offer was no longer on the table. A story by Shirley in the third issue of

Spectre

, “Had We but World Enough” (another of Stanley’s allusive titles), hints at their frame of mind in the spring of 1940. A boy and a girl, walking in the park, want to get married but are waiting for him to get a job. They entertain themselves by fantasizing about how they will set up housekeeping together:

“If we had fifty dollars every week we could have a swell place. I’d buy furniture and dishes and things.”

“We’d have to have a place with a telephone,” he said.

“To handle your business calls, no doubt? I don’t want a telephone; I want a brown and yellow living room with venetian blinds and comfortable chairs . . .”

“We’d have children, too.”

“The hell with you,” she said. “You think I’m going to have children and ruin my whole life?”

They laughed. “Twenty children,” he said. “All boys.”

The answer came in early May, when Stanley received a letter from Bruce Bliven, editor of

The New Republic

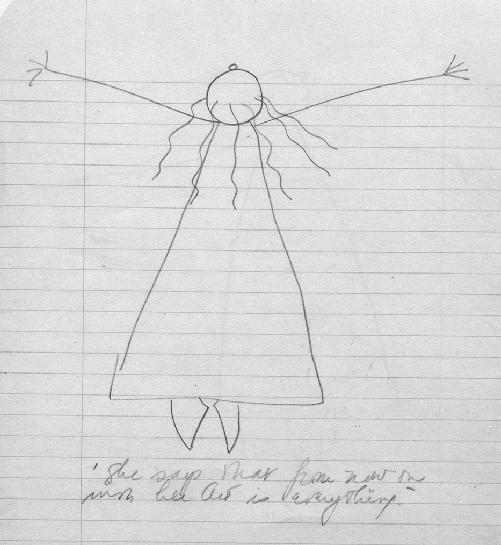

, informing him that he had won the magazine’s college writing contest. The prize was a summer job in the magazine’s New York office. The pay was low and the job was temporary, but it was a start. Stanley accepted at once. If there had ever been any doubt that the two of them would move to New York immediately after graduation, there was no longer. A cartoon Shirley drew around that time depicts her with her arms out wide and her head thrown back in exultation. The caption reads: “She says that from now on with her[,] art is everything.”

5.

NEW YORK,

NEW HAMPSHIRE,

SYRACUSE, 1940–1942

“well, i like the title,” said stanley. “what’s the plot?”

“what plot?” i asked.

“the plot of the novel,” said stanley, wide-eyed.

“don’t be silly,” i said. “i let the characters make the plot as they go along.”

“you mean you don’t have any idea what’s going to happen?”

“not the slightest,” i said proudly.

“but,” said stanley rather breathlessly, “people don’t write novels like that.”

“

i

do,” i told him very smugly indeed.

—

Anthony

(unfinished novel)

I

N AN INFORMAL CEREMONY—“A BRIEF THREE-MINUTE THING,”

as Stanley described it—Shirley and Stanley were married on Tuesday, August 13, 1940, at a friend’s Manhattan apartment. On the marriage license, Shirley listed her birth year as 1919. It was as if the three miserable years she had spent in Rochester had been erased and her adult life had officially begun when she entered Syracuse and met Stanley—which,

in truth, it had. In a gruffly worded invitation, Stanley advised friends to “miss the ceremony and come for the liquor.” Formal dress was not expected, he emphasized, and neither were presents: “it is not that sort of wedding.”

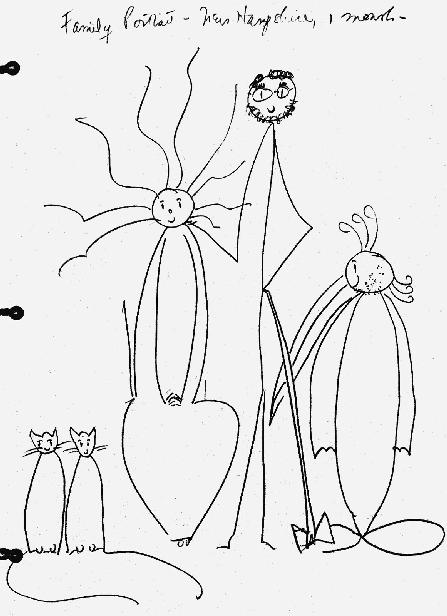

Shirley’s drawing of herself and Stanley in New Hampshire, fall 1941. The figure with the beak is the bird she called her “familiar.”

If Stanley’s tone sounds grim for a man about to be married, it was likely because the months leading up to the wedding had been filled with tension. The couple faced determined parental opposition from both sides. Moe had first confronted Stanley about the relationship in the summer of 1938, when he discovered long-distance charges on the phone bill and realized Stanley had been calling “that Mick,” as he referred to his son’s

shiksa

girlfriend. In the spring of 1940, back

at their home in Brooklyn, the two of them had their first serious talk about what would happen when Stanley and Shirley were married—

when

and not

if

, he reported to her afterward. The dire news out of Europe must have increased Moe and Lulu’s opposition to the marriage. Moe had distant relatives still in Lithuania; two years earlier, his synagogue had been one of the few in New York to hold a service commemorating Kristallnacht. Moe told Stanley he wouldn’t say Kaddish for him—the signally harsh measure of essentially declaring his son dead, or at least dead to the family—but “he would be awfully sore and awfully hurt and he wouldn’t talk to me for years.” Moe also enlisted his friends in the campaign. Stanley got a call one day from his former boss at the paper plant in Erving, who said that he understood perfectly well the desire to sleep with non-Jewish women—in fact, he had a number of such mistresses himself—but, out of respect for his mother, he didn’t marry them. Stanley insisted that his relationship with Shirley was, as he put it, “the real business,” and by the end of the conversation the man was offering to help them both find jobs in New York. Lulu, for her part, seems to have kept quiet about the matter; she could not have been pleased, but she also would not ostracize her elder son.

Leslie and Geraldine Jackson were no happier about the marriage than Moe was. In the two years since a scruffy Stanley literally jumped off the porch rather than meet his future in-laws face-to-face, the Jacksons’ attitude toward him had deteriorated even further. “they will do anything in the world, says my father, to prevent my marrying you, even unto bribery and threats,” Shirley reported. The cross-country road trip the previous summer had likely been motivated at least in part by their desire to put distance between their daughter and her unsuitable boyfriend. In the spring of 1940, Shirley’s parents announced that for a graduation present they were buying her a plane ticket to spend the summer in California—a major extravagance in the early days of air travel and another obvious effort to separate the couple. They were crestfallen when she told them she would not go: her plan was to move to New York immediately and look for a job. But Geraldine did not give up. “i have come to the conclusion that my family is not so dumb,”

Shirley wrote to Stanley while she was at home in Rochester over the Easter holiday.