Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (23 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

In fact, both Shirley and Stanley found country life suited to productivity. Shirley managed to place her Macy’s piece in

The New Republic

—the magazine paid her only twenty-five dollars, but it was her first commercial publication. “Shirley Jackson, the wife of Stanley Hyman, is living in New Hampshire and writing a novel,” her author’s note read. From this point on, her identity was double. Her byline was “Shirley Jackson,” and always would be. But in her personal life, like almost all women of her era, she used her husband’s name. This doubling could play out in amusing ways: her agent’s office would sometimes send royalty statements or other formal correspondence addressed to “Shirley Jackson” but with the salutation “Dear Mrs. Hyman.” She never commented on why she chose not to use the name Hyman professionally, though in later years she was grateful for the relative anonymity it gave her. When the family moved to Westport, Connecticut, after the publication of “The Lottery,” many of their neighbors did not realize that the woman they knew as Mrs. Stanley Hyman was the writer Shirley Jackson.

Hyman, in addition to his

New Yorker

work, speculated that he might spend the long winter evenings writing a biography, perhaps of the abolitionist Wendell Phillips. Walter Bernstein had signed a contract that fall with Viking on the strength of his

New Yorker

pieces, one of which had been selected for the magazine’s first anthology,

Short Stories from the New Yorker

(1940), an effort to establish its bona fides in serious fiction. Bernstein assuaged Hyman’s jealousy somewhat by introducing him to his agent, whom he considered both “mentor and friend”: Frances Pindyck of the Leland Hayward Agency, a motion-picture talent agency with a sideline in writers. A petite, bubbly, intelligent Jewish woman from New York who graduated from Syracuse a decade before Jackson and Hyman, Pindyck counted among her clients Dashiell Hammett (

The Thin Man

) and Betty Smith (

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

). Within a few months she would be shopping around Jackson’s work, too.

Jackson started and abandoned several novels over the next few years, so it’s hard to say exactly what she was writing in New Hampshire. It might have been

I Know Who I Love

, an unfinished novel about

a young woman named Catharine, “thin and frightened, born with a scream and blue eyes,” the daughter of a stern minister who would have preferred a son—Geraldine, in disguise. (The first section of the novel would eventually be published posthumously under the same title.) The bulk of the story has to do with Catharine’s painful memories of high school (“worse for Catharine than any other time in her life”): the girls who tease her by singing “Ratty Catty, sure is batty,” her mother’s disapproval of a girl she befriends, the boy at a party who refuses to kiss her in a kissing game. She envies the girls with high heels and curly hair who go to school dances while she and “her three or four friends gave little hen parties where they served one another cocoa and cake, and said, ‘You’d be cute, honestly, Catty, if you had a permanent and wore some makeup.’ ” She fantasizes about returning someday, “a famous artist with a secretary and gardenias,” and scorning the people who once mocked her.

The minister dies young, and Catharine, a secretary at age twenty-three, brings her mother to live with her, who despite this gesture calls her “an ungrateful, spoiled child. . . . I don’t know what I did to deserve a daughter like you.” Her only happy memories are of a man whom she met in business school, who calls her “Cara” and jokes with her about her parents’ disapproval. She keeps a letter from him in a cedar box with her other treasures: a charm bracelet, a matchbook from a nightclub, and a rejection slip for a watercolor she once submitted: “She kept it . . . because it had been addressed to her name and address by someone there at the magazine, some bright golden creature who called writers by their first names and sat at chromium bars and walked different streets than Catharine did.” The autobiographical elements are obvious—the hen parties, the boyfriend who is the target of parental disapproval, the magazine rejection. But Jackson was starting to show a greater ability to distance herself from them, translating elements of her own experience into an alien environment.

In contrast to the isolationist indifference shown by many Americans to the catastrophe that was threatening Europe, American Jews were visibly more anxious—as was Jackson, now married to a Jew. Her

growing concern about the war is evident in a story she wrote for Harap for a contest run by

The Jewish Survey

. “The Fable of Philip” depicts an anti-Semitic art student who tries to rally his classmates against the Jewish students, who he complains are advancing unfairly by paying others to do their work for them (“they’ve got money to burn”) and taking opportunities from others. Eventually he is suspended for an act of vandalism against a Jewish professor, and his family, which includes a Jewish grandfather, disowns him. Even the German-American Bund proves unhelpful, and in the end he settles for a job in the wholesale paint business. As the title suggests, this “fable” is a simple piece of writing with an obvious political message, more a piece of propaganda than a true short story. Harap, failing to understand Jackson’s intentions, was dismissive. “I cannot, as a friend of yours, allow this story to be published,” his rejection letter began. The plot lacked “movement,” and Philip was “a stereotype right out of

The Jewish Survey

’s rogue’s gallery.” Jackson took the criticism hard—she remembered it in an angry letter to Harap several years later. Throughout her life, she had trouble handling rejections; later Hyman and her agents would shield her from them as much as possible.

Her consolation was her first magazine story. “My Life with R. H. Macy” appeared in

The New Republic

on December 22, 1941. The magazine’s second issue after Pearl Harbor, it was devoted almost entirely to analysis of the war. The lead editorial blamed officials in Washington for following a policy of appeasement, which had made it impossible to prepare adequately for the possibility of war, but urged the public not to indulge in “either excessive pessimism or optimism.” Other articles examined Japan’s possible strategy and encouraged support for Russia as “our strong and admired ally.” Earlier in the year, the magazine had surveyed its contributors about whether they supported an immediate declaration of war against Germany. Along with about half the respondents, Hyman came out in favor: “We should prosecute the war on Hitler with all possible fervor, including the immediate creation of a second front in Europe and the rapid crushing in that gigantic pincers of the old pincers-master himself,” he had written. Now the question was moot.

THE LANDLADY’S PREDICTIONS

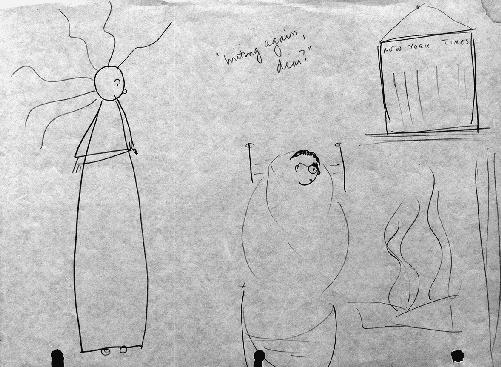

about winter in the country proved accurate. Temperatures averaged as low as single digits. Shirley and Stanley brought in an extra stove, but it wasn’t enough. Shirley’s cartoons depict them both wrapped in blankets; the bird, too, wears a scarf. Even in top form, Shirley probably did not have the constitution to endure a New Hampshire winter in an insufficiently insulated house. But now her health was a little more delicate than usual. Around the start of the new year, she began to suspect she was pregnant.

In January 1942, Shirley and Stanley decamped to Syracuse for the rest of the winter. There they could get by nearly as cheaply as in New Hampshire, and they still had an assortment of acquaintances at the university, including their mentor Leonard Brown and their old friend Seymour Goldberg, who became a near constant companion. One night after dinner, reminiscing about

Spectre

and people they had known, they realized their college stories were fertile material for fiction. Troubled by how much he had already forgotten, Stanley resolved to keep a journal and persuaded Shirley to join him: they would write every day and periodically share their journals with each other.

Shirley, of course, was no stranger to journal keeping, and lately her cartoons had become a kind of personal chronicle. But she hadn’t tried to write a daily diary since high school. It was in her letters—from the

scribbled notes to Elizabeth Young and Jeanou in random pages of her college notebooks to the lengthy missives to Stanley she typed during the summers—that she gathered her thoughts and assessed her life. Now, the return to journal writing reopened her confessional vein. Her “official” typewritten journal, the one she shared with Stanley, was cool and analytical. But now and for the rest of her life, there would be other spasms of diary writing: just a page or two at a time, hidden among a pile of drafts for a novel or notes for a lecture, often written at a moment of crisis.

Stanley, on the other hand, kept his journal every single day for a month and a half (often signing off with the Pepysian flourish “And so to bed”), then abandoned it entirely. When he set his mind to something, he did it—but only as long as it held his interest. His love of routine is evident in his daily habits. He typically stayed in bed until late morning or early afternoon; Shirley would get up earlier to prepare coffee for him. (Arthur, his brother, would later remark that Stanley had preserved one aspect of their traditional Jewish upbringing: like a Talmudic scholar, he managed to have his wife take care of all the day-to-day matters so that he could concentrate on his studies.) Their room didn’t include a full kitchen, so they took most meals at the Greeks, their old college hangout, which stayed open until two in the morning and conveniently allowed them a generous line of credit. After a late breakfast or early lunch, Stanley would return home to work through the afternoon. He continued to write Comments for

The New Yorker

as well as reviews for

The New Republic

, and read both magazines from cover to cover the day they came out. He also scoured the newspaper daily, filing away articles he thought might later be useful for Comment ideas or reviews. Throughout his life, Stanley maintained a system of taking rigorous, organized notes on all his reading. As he read, he would make tiny notations on a bookmark; later he would type them up and file them.

Shirley’s habits were less regular, as they always would be: she often spent the afternoon drawing cartoons or having coffee with a friend. They were sharing a single typewriter, and Stanley generally commandeered it. After her resounding rejection from Louis Harap,

she felt uncertain about how to proceed. “Shirley is still working on funny pieces, but hasn’t turned out anything yet that is really good,” Stanley wrote to Harap. She followed through with attempts at a few stories drawn from the lives of their college friends: one centered on June Mirken’s painful breakup with a boyfriend. Shirley wanted to write about the episode because it troubled her, but she was unsure how to make it into a story. To do so, she mused, she’d “have to put it down first the way it happened and then go back and cut out all the drama until it stopped being what had happened and turned into a story. it’s a good story . . . the only thing wrong with it is that it happened.” Later she would often use the technique of basing a story on an anecdote someone told her, “thinking about it, turning it around, thinking of ways to use a situation like that in order to get a haunting note.” Eventually she would realize that, as she put it in a lecture, an “accurate account of an incident is not [a] story.” But she hadn’t yet figured out how to transform a life event into fiction.

In Stanley’s opinion, her stories needed to have a “wow ending, like Mr. Hemingway,” whose collected stories he had given Shirley for their first Christmas together. This advice was largely in sync with the literary taste of the time, particularly as it was influenced by

The New Yorker

, which in the years since its inception in 1925 had expanded beyond its initial purview as a humor magazine into a destination for at least moderately serious fiction. By the early 1940s, the “

New Yorker

short story” was already an identifiable type. Exemplified by writers such as Shaw, James Thurber, and John O’Hara, this style of fiction was brief (no more than a few pages), genteelly oblique, and virtually plotless. Instead, the writer used precise observations and keen aperçus to illuminate some cold truth about contemporary life, often revealed in a bitter twist at the end. The “wow ending” was far from universal: Thurber’s stories in particular often meandered to a close. But when it was done well—O’Hara and Shaw were particularly skilled in this regard—the final stab could reverberate through the entire story to alter the reader’s perception of what had taken place.

The

New Yorker

style was not universally admired—even the magazine’s editors sometimes felt uneasy about it. Katharine Angell (later

Katharine White), who joined the magazine’s staff in August 1925, six months after its founding by Harold Ross, and was in charge of the fiction department for many years, wrote to an early contributor that “we want fiction and we want short stories, and yet when it comes right down to it Mr. Ross feels the stories we use have to be quite special in type—

New Yorker

-ish, if that word means anything to you.” Lionel Trilling, the soon-to-be eminent literary critic who had recently been hired as the first Jewish full-time professor in Columbia University’s English department, objected to the magazine’s already notorious slick and glossy style in a critique of

The New Yorker

’s fiction in

The Nation

in the spring of 1942. All the authors, Trilling argued, were “the same anonymous person, and you feel about them that, just as any scientist might take over another’s research or any priest take over another’s ritual duty, almost any one of these writers might write another’s story in the same cool, remote prose. . . . Somehow, despite their admirable technical skill and despite their high earnestness, these stories have a mortuary quality; they are bright, beautiful, but dead.” Part of the problem, Trilling believed, was the magazine’s strict limits on length: the stories have “just room enough to make the sharp perception but not room enough for a play of emotion around it.” And their themes were as indistinguishable as their style. Trilling found the stories “grimly moral,” invariably devoted to a social lesson about “the horrors of snobbery, ignorance, and insensitivity and . . . the sufferings of children, servants, the superannuated, and the subordinate.”