Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (22 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

Jackson and Hyman, too, felt the pinch of poverty. As an editorial assistant at

The New Republic

for the summer, Hyman earned $25 per week—only a few dollars more than he had made at the paper mill in Erving. (For comparison, Cowley was paid $100 a week when he became literary editor a decade earlier.) Hyman quickly earned himself a reputation as a hard worker and was well liked in the office, not least for his sense of humor. After his first piece was published, he bombarded Bruce Bliven, the magazine’s editor, with a series of prank postcards, all signed by people with the last name Hyman, attesting that it was the best thing ever to appear in the magazine. Bliven even kept him on for a few extra weeks as a favor.

When the position had to end that fall, Bliven wrote Hyman letters of introduction to editors all over town: “he is highly intelligent, writes rapidly and well, has the gift of humor and I think has the makings of a crack newspaper man.” Hyman wrote his own letter to Gustave Lobrano, then a young staffer at

The New Yorker

, who within a few years would be Jackson’s editor there. “i choose you because i have no idea who is in charge of reading applications for employment from bright

young men with convictions of innate superiority who have just been graduated from coeducational universities in the east,” the first draft inauspiciously began. This missive—presumably in edited form—somehow made its way to the desk of William Shawn, then the assistant editor in charge of the “Talk of the Town” section. It probably helped that Hyman dropped Walter Bernstein’s name.

In those days, “Talk of the Town” opened with a page or two of brief, unsigned items—sometimes humorous, sometimes pointed—known as “Comment.” In January 1941, Shawn invited Hyman to contribute Comments; he would do so for the next decade. He also began writing freelance book reviews for

The New Republic

, the Marxist magazines

The New Masses

and

The Jewish Survey

, and other publications. The work was demanding: one of Jackson’s early drawings of the two of them shows Hyman staggering under a giant pile of books. Still, it wasn’t enough to live on. Hyman was desperate enough to take a job in a sweatshop, sewing brassiere straps, but he was so bad at it that he was fired. For several months in 1941, he collected unemployment. They economized by using the same coffee grounds for several days in a row, but “we have to have oranges, don’t we, hell, you get scurvy or something,” Jackson grumbled.

Jackson held a series of odd jobs, including staving off creditors at an advertising agency and writing scripts for a radio station—mostly commercial pander aimed at housewives (“How can I make my dinner table look attractive without spending much money?”). In a satirical piece, she parodied the indignities of the job interview: “i am twenty-three [actually twenty-five], just out of college, authority on all books and a great writer, can type, cook, play a rather emotional game of chess, and have a republican father which is no fault of mine.” A stint selling books at Macy’s during the Christmas season served as fodder for “My Life with R. H. Macy,” in which Jackson poked fun at the store’s practice of referring to employees by number rather than name and the cryptic abbreviations she was expected to decipher (her receipt for a pair of free stockings reads “Comp. keep for ref. cuts. d.a. no. or c.t. no. salesbook no. salescheck no. clerk no. dept. date M. . . . 13-3138”). The piece would appear in

The New Republic

the following year.

With the exception of a few short poems printed under pseudonyms in

Tabard

, the Syracuse literary magazine that June Mirken was running in place of

Spectre

, Jackson published nothing for a year and a half after graduation. She tried her hand at

New Yorker

–style casuals and “Talk of the Town” pieces, but nothing other than the Macy’s piece seems to have made it past a first draft. Her poem “Portrait of the Artist, with Freudian Imagery” captures her discouragement:

She might have disguised herself as a pencil

Moving, unseeing, between a world of men

And another world of words; but there, again,

She would have found no paper long enough, and no ink plenty. . . .

Hyman submitted it to the poetry editor at

The New Yorker

, who returned it with the terse comment “Not for us, it seems.” Jackson expressed her frustration with magazine work, politics, the impending war, and all other annoyances of their life in New York in a single immortal couplet, verbosely titled “song for all editors, writers, theorists, political economists, idealists, communists, liberals, reactionaries, bruce bliven, marxist critics, reasoners, and postulators, any and all splinter groups, my father, religious fanatics, political fanatics, men on the street, fascists, ernest hemingway, all army members and advocates of military training, not excepting those too old to fight, the r.o.t.c. and the boy scouts, walter winchell, the terror organizations, vigiliantes, all senate committees, and my husband”:

i would not drop dead from the lack of you—

my cat has more brains than the pack of you.

BY THE TIME HYMAN

began working at

The New Yorker

, the war had managed to invade that magazine’s mild-mannered pages. For most of the 1930s,

The New Yorker

had clung stubbornly to its original identity as a humorous publication, declining to take political positions and treating even the most ominous news with the evenhandedness that

consistently characterized its tone. In April 1933, E. B. White opined in a Comment that recent developments in Germany had sent the nation “a thousand years into the dark,” but the remark was buried low in the column, after an item on trout fishing. In 1936, White noted the irony that some American Christians who opposed the Nuremberg laws continued to patronize “restricted” establishments, but his editorializing struck a false note: “Americans’ philosophy seems to be that it is barbarous to persecute Jews, but silly to suppose that they have table manners. Of the two types of persecution, Germany’s sometimes seems a shade less grim.” This takes the ironic pose one step too far.

Irwin Shaw, one of the most prolific

New Yorker

fiction writers in those days, may have done more than any of the magazine’s other writers to raise awareness of the coming disaster. “In almost everything I wrote . . . this thing was hanging like a backdrop,” he said later. The magazine was known for its reluctance to engage with overtly Jewish topics, but Shaw managed to work them in. His story “Sailor off the Bremen” describes an anti-Nazi demonstration encroaching upon a bohemian New York City scene that would prefer to ignore politics. (This story, incidentally, seems to mark the first appearance of the term “concentration camps” in the magazine.) In Shaw’s “Weep in Years to Come,” published in July 1939, a newsboy continually shouts “Hitler!” in the background as a couple leave a movie theater. Initially they carry on with their conversation, but eventually the subject of the war takes over—a metaphor for what was taking place in the city at large.

Walter Bernstein, who had drawn an unlucky number, was the first of Hyman’s friends to be drafted; he left for Fort Benning in February 1941. In March, Hyman received his first notification from the Selective Service. As a married man, he was classified 3-A: deferred, for the time being. But the war found its way into his Comments, which had initially tended toward the innocuous. Now, in an item about advice that Eleanor Roosevelt had recently offered young women on how to avoid being the victims of crime, he included a reference to a speech given by a Navy admiral to families in Honolulu, warning about anonymous phone calls used to track ship movements. (Appearing less than six months before

Pearl Harbor, it now feels eerily prescient.) At Gimbel’s one morning shortly after the Office of Production Management seized the nation’s supply of raw silk, he watched as women responding to an advertisement allowing unlimited purchases of silk stockings stampeded the hosiery department. Hyman wrote about the scene in the language of a military exercise: “The terrain unquestionably favored the invaders, many of whom were clad in light cotton dresses. . . . The defenders, back of the counters taking orders, were hard pressed to maintain their lines in the face of opponents who deployed with skill and single-mindedness. . . . Such is our bulletin from the front during what may be the last days, for all we know, when a woman can walk into a department store and buy as many pairs of silk stockings as she has a mind to.” The magazine still sought the humor in virtually any situation.

A summer heat wave brought “tense and humid days,” making New Yorkers so testy that—as Hyman reported in another of his Comments—a man in Coney Island bit a police officer. Five people died; the warm front stretched as far west as the Dakotas, setting records in Indiana. Shirley, always affected by seasonal allergies, suffered from an excruciatingly painful headache that would not go away. Her parents convinced her to make a trip to Rochester to visit the family doctor, who diagnosed her with a sinus infection and said she needed sleep, exercise, and green vegetables.

There was then, as there is now, no shortage of doctors in New York. Shirley’s parents were using her illness as an excuse to induce her to come home. Geraldine and Leslie, as a matter of pride, would not come to New York, but they longed to see their daughter, even if they disapproved of her life choices. “This is a week I have owed them for so long,” Shirley wrote to Stanley plaintively from Rochester. Still unaware of the marriage, they greeted her with a box of her favorite peanut brittle and did not mention Stanley at all: when he called on the phone, Geraldine and Leslie shut themselves in their bedroom until the couple finished talking. Stanley, who spent the week in Syracuse with friends, wanted to visit, but Shirley discouraged him, worried about her parents’ reaction. “Like always I don’t know how to see you [in Rochester] and it is so

funny and different if you come here and I am always scared.” Stanley was dismissive. “there is some incredible psychological hold that house has on you that puts us back three years as soon as you go through the door,” he harrumphed. But he obediently stayed away, arriving to collect Shirley for the trip back to the city at a time when no one else was home.

Back in Manhattan, Shirley and Stanley came upon an advertisement for a remote cabin on the evocatively named Toad Hollow Road, outside the town of Winchester, in southern New Hampshire. A dozen miles from Keene, the nearest major town, it was fully furnished and came with a wood-burning kitchen stove. “The house looks fresh and clean and cool,” their prospective landlady, Gwynne Ross, assured them. Across the dirt road was a brook that had been dammed up to make a swimming hole, “marvellous if you like cold water.” It wasn’t the “house with no sides on top of a mountain” Shirley had once dreamed of, but it was close. Perhaps there, in the quiet, she would finally be able to calm the “insane seeking for some overwhelming stability” she had once lamented.

The conditions, Ross cautioned, were rustic. There was a telephone, but no gas or electricity. The kitchen had running water, but the bathhouse was a shed outside. More important, the plumbing was not designed to be used during the winter, and the pipes would have to be buried so as not to freeze. “Have you ever lived through a winter in the country before? There is quite a technique to it,” Ross warned them. Sandbags had to be stacked around the outside of the house and an adequate supply of wood stockpiled. “With reasonable care, damage can be prevented, but you have to be on the qui vive all through the winter.” The rent was only one hundred dollars for the entire year. Her warnings notwithstanding, they took it.

Although Shirley’s driving skills were rudimentary at best (Stanley could not drive and never would learn), they bought an old car from her former nemesis Florence Shapiro for twenty-five dollars—it was “a real tin lizzie,” Florence recalls—and headed for New Hampshire. “It has been wonderfully warm and incredibly lovely, with the leaves turned red and me not yet turned blue,” Stanley wrote in October to

Louis Harap, a friend of Jesse Zel Lurie’s and the editor of

The Jewish Survey

, for which he wrote occasional reviews. He was happily nursing blisters and calluses from chopping wood and shoveling dirt, they had found and adopted two kittens, and

The New Yorker

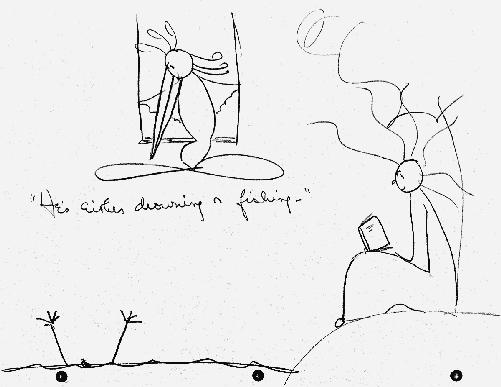

continued to run his Comment items every other week or so. “The farm seems to agree with you,” Shawn told him. In cartoons depicting their rural life, Shirley gently poked fun at Stanley’s ineptness at surviving in the country. “He’s either drowning or fishing,” she comments to the eagle-penguin character as Stanley flails in the creek, only his arms visible above the water. Her drawings were changing. The bird now functioned as the straight man or sounding board to whom Shirley’s comments—funny, wry, or bitter—were directed: her audience. In one drawing, Shirley labels him a “familiar.”

Stanley’s main adaptation was growing a beard, which gave him the professorial look he would always cultivate. He invited Harap to visit—and to help out: “there is still wood to be cut, a cesspool to be dug, and many other features of a pleasant weekend.” Shirley, he reported, had “gone completely rustic . . . baking bread and putting up cinnamon jelly with a passionate, unquestioning fury.” She would send Harap a story to publish “as soon as she can get away from the oven to the typewriter.”