Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (25 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

NEW YORK,

1942–1945

In some respects, having a baby is roughly like being in the path of a major hurricane. Or like having all your relatives come at once for a two-week visit. . . . Or like discovering suddenly that you have only one hand when you thought you had two. Or like discovering suddenly, as a matter of fact, that you have only two hands when you hoped you had four.

—

Special Delivery

“

M

Y MENAGERIE NOW INCLUDES TWO SNAKES, ONE SMALL

snapping turtle, twenty-three salamanders, eight frogs, and several million polliwogs,” Hyman reported happily to Louis Harap in May 1942. Now that the weather was warmer, he and Jackson had returned to New Hampshire, and he was again indulging his childhood fascination with natural science—by summer, the snake count reached nine. He gathered food for them himself, catching chipmunks, frogs, or a handful of grasshoppers for his pets. The weather, at last, was beautiful, and Jackson’s pregnancy was proceeding easily. Harap was drafted in July, but he did make it up to visit beforehand, and so did Jesse and Irene Lurie. Jackson and Hyman spent their days swimming, picnicking, and

picking wild berries. Hyman’s

New Yorker

Comments were still running at least once a month, and he was publishing occasional book reviews in

The New Republic

and elsewhere. He had also been in contact with a young man named Ralph Ellison.

Self-portrait, c. 1942.

“Sometimes we have such good luck in acquiring our friends that it’s impossible not to suspect that fate had a hand in their appearance,” Ellison later recalled. Born in Oklahoma City, he attended Tuskegee Institute in Alabama before coming to New York in 1936, just as the initial glow of the Harlem Renaissance was starting to fade. Hyman may have noticed his writing as early as 1938, when Ellison, mentored

by Langston Hughes and later Richard Wright, made his debut in

The New Masses

, reviewing a biography of Sojourner Truth. In 1942, he was named managing editor of

Negro Quarterly: A Review of Negro Life and Culture

, a new journal of African-American writing backed by left-leaning intellectuals, including the novelist Theodore Dreiser and the Harlem Renaissance philosopher Alain Locke. Ellison’s plans for the magazine were ambitious: to stimulate “discussions concerning the relationship between Negro American culture and history and that of the nation as a whole” while covering sociology, literary and cultural issues, and politics from a socially radical perspective, with writing from “the best critical minds, whether black or white.” But the initial response from white critics was disappointing. Ellison discovered that while many of the critics he admired “knew the spirituals well enough to sing a few verses and had been touched by jazz and Negro American dancing styles, few were prepared to give these cultural products the finest edge of their sharply honed minds.”

Hyman—young, eager for exposure, and passionately antiracist—was an exception. After reading the magazine’s first issue, he immediately sent Ellison a postcard offering his services as a reviewer. Ellison was already aware of Hyman’s work, complimenting him on an article he had recently published about Steinbeck in the

Antioch Review

. “Between the sophisticated

New Yorker

and the deadly earnest

Quarterly

there ought to have been a chasm,” writes Ellison’s biographer Arnold Rampersad. But the two men’s interests were already aligned. Like Hyman, Ellison was attracted to folklore and mythology as an influence on fiction (including his own)—an interest that had begun at Tuskegee, when he followed T. S. Eliot’s footnotes on

The Waste Land

to Jessie Weston’s book

From Ritual to Romance

, a key text in myth and ritual criticism, which interprets the Grail legend as rooted in primitive myths of the death and rebirth of a fertility god. In 1940, Ellison published an essay in

The New Masses

that began with an extended reference to

The Grapes of Wrath

as a novel that had recently “explod[ed] upon the American consciousness”—including, of course, Hyman’s.

Their affinities were personal as well as intellectual. Both men were active and respected in the New York intellectual scene, yet in important

ways outsiders to it. “A Jew married to a gentile, Hyman saw himself as a cosmopolitan intellectual—just as Ralph, labeled a Negro, saw himself as a citizen of the world,” Rampersad writes. The two men met for the first time that summer and started seeing each other regularly in the fall, when Jackson and Hyman returned to New York. Hyman’s first piece in

Negro Quarterly

, a review of the novel

Tap Roots

by the white Southern writer James Street, appeared in the fall 1942 issue.

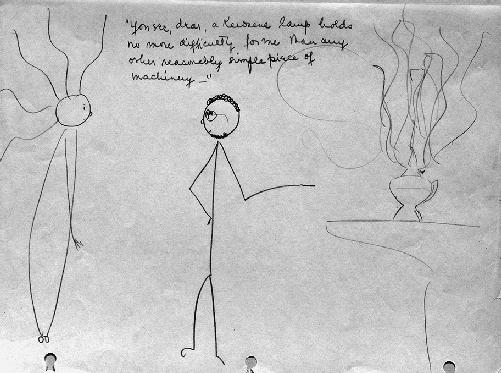

After a burst of writing that spring, Jackson had been less productive. Fran Pindyck had shopped around a few of her stories without success. Jackson amused herself by drawing cartoons and putting together an illustrated ABC book called

The Child’s Garden of New Hampshire, or, How to Get Along in the Country

, written in a parody of the gruff New England style. “D is for Deer—which is a season”; “I is for Idle, which is the kind of hands we find work for” (illustrated by an axe and a pile of chopped wood); “S is for Stanley, easily recognizable by the

New York Times

he carries in his hand”; “U is for Uppity, which is what summer folks are”; “Y is for Yesterday, which is when the mailman started out.” For a time, she may have seriously considered becoming a cartoonist.

Jackson’s humor could not mask the very real alienation she felt from her neighbors in Winchester. Part of the reason she and Hyman urged their friends from New York to visit was that they felt isolated:

their only local friends were a pair of Communists who ran a dog kennel. The fancy-newspaper-reading, Sauternes-drinking renters hardly fit in, and their neighbors let them know it. A cartoon depicts their house surrounded by figures listening at the windows as Jackson complains, “I can’t understand how the neighbors find out that we have company from New York.” They also clashed with their landlady, who lectured them about the “mutual assistance” country people expected after they neglected to help repair the bathhouse, which they had managed to burn down. (Jackson’s cartoon about the incident shows Hyman calmly regarding a kerosene lamp as it bursts into flame.) Jackson would later say that “The Lottery” grew out of this period in their lives—not, as is commonly thought, from the insular community of North Bennington, Vermont, where they were living when she wrote the story. She would give many explanations—or partial explanations—for that story’s genesis; still, the influence of New Hampshire seems meaningful.

Perhaps to her relief, their second stay in New Hampshire was even shorter than the first. In July 1942, William Shawn, then

The New Yorker

’s managing editor for “fact” pieces, offered Hyman a full-time job at a salary of thirty-five dollars a week, plus bonuses for extra productivity, doing much the same work as he was already: writing Comments, casuals, and perhaps some “Talk of the Town” items. The war had hit the magazine hard: some of the staff had already been drafted, while others, including A. J. Liebling and Janet Flanner, were sent abroad to cover the news from Europe. Walter Bernstein, for whom Harold Ross had found a job with

Yank

, the Army’s new weekly magazine, also sent occasional dispatches back to

The New Yorker

from Europe and the Middle East, including the first interview with the new Yugoslav leader Marshal Tito conducted by an American journalist.

The New Yorker

was “a worse madhouse than ever now, on account of the departure of everybody for the wars, leaving only the senile, the psychoneurotic, the maimed, the halt, and the goofy to get out the magazine,” E. B. White complained in a letter to his brother.

Hyman would be among them. Called before the draft board again in March 1943, he failed his physical. He later liked to joke that the Army doctor told him he had the organs of a middle-aged man. He probably

did, thanks to his sedentary lifestyle, but in fact it was his poor eyesight that disqualified him. He and Jackson would have to watch the war from afar. His friend and colleague Joseph Mitchell was also disqualified from war service, because of a history of ulcers. Mitchell’s inability to participate in the war effort was a source of guilt and resentment for the rest of his life: he complained of sitting at home in New York while friends like Liebling and Flanner wrote “reputation-making” articles. Hyman may well have felt the same.

When he offered Hyman the job, Shawn warned that “living in New York has its disadvantages, the newest of which is the prospect of air raids.” The city had been transformed by the war. Workers mobilized to help with war production efforts—everything from building ships in the Brooklyn Navy Yard to making uniforms at Brooks Brothers. Ration books were issued for sugar, gasoline, and soon coffee; anyone wishing to buy a new tube of toothpaste, made from metal, had to turn in the old one. Typewriters, too, were rationed—a special hardship for writers. At the war’s height, a ship laden with supplies or men left New York harbor every fifteen minutes. In the quiet of the New Hampshire woods, the war could be ignored; in the city, it could not.

Wartime chaos notwithstanding, it was Hyman’s dream to work at

The New Yorker

. Now, at age twenty-three, he had achieved it. Although he wrote little for the magazine in his later years, he kept the title of staff writer until his death. Even after he began teaching at Bennington, he wrote nearly all his correspondence on

New Yorker

letterhead—a symbol of his attachment to the magazine and his pride in the status it conferred. Whenever he visited the office, he replenished his supply. His colleague Brendan Gill would later write of Hyman’s “magic briefcase”: he would leave Bennington with a briefcase full of whiskey and would return with it weighing exactly the same amount, now full of

New Yorker

stationery.

On September 1, as German troops were beginning their ill-fated advance on Stalingrad, Jackson and Hyman traded their cabin in the woods for a brick row house at the top of a hill in Woodside, Queens, then known as “the borough of homes.” The extension of the subway in 1918 had generated a housing boom, and the quiet streets were lined

with new semidetached English-style houses with gardens in the front and the rear. Their new house was just around the corner from Jesse and Irene Lurie, who were soon to have a baby of their own, and a short subway commute to Manhattan. Their experiment in country living was over—for now.

FOR MANY YEARS

, Shirley maintained a running joke that she was conducting a contest between the number of children she produced and the number of books she wrote. Eventually the books pulled ahead, but at first the children kept pace, with a new arrival every three years, almost to the day. Laurence Jackson Hyman (Laurie) was born on October 3, 1942, followed by Joanne Leslie (Jannie) in November 1945, Sarah Geraldine (Sally) in October 1948, and Barry Edgar in November 1951. Like nearly all men of his era, Stanley was a hands-off parent, preferring to sequester himself with his typewriter behind a closed door. “Bring ’em to me when they can read and write,” he liked to say. Shirley once commented that at age two, Laurence’s definition of “Daddy” was “man who sits in chair reading.”

But Shirley, all her children remember, was an imaginative and unconventional mother. Several years before Dr. Benjamin Spock’s best-selling

Baby and Child Care

would advocate a more relaxed style of child rearing than the strictly routinized methods that had become standard in America, she embodied his intuitive, casual approach. Though she couldn’t help channeling some of Geraldine’s admonishments—“A lady doesn’t climb trees,” she would tell her daughters, whom she made wear garters and high heels as teenagers—she was determined to give her children an upbringing altogether different from her own: down to earth, creative, loving. Early in

Hill House

, Eleanor, the protagonist, encounters a little girl having a tantrum because she cannot drink her lunchtime milk out of her usual cup painted with stars. “Insist on your cup of stars,” Eleanor silently bids the girl. “Once they have trapped you into being like everyone else you will never see your cup of stars again.” Shirley, who would one day decorate the kitchen ceiling with stars, wanted to be the kind of mother who offered a cup of stars.