Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (11 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

The demon in the mind

. This was Jackson’s obsession, perhaps her fundamental obsession, throughout her life. Often it appears metaphorically as the source of the evil deeds people commit against one another, as in her story “The Lottery”: what else can explain the villagers’ mad adherence to a tradition that requires them to murder one of

their neighbors? But it takes literal forms as well. In the early stories that would be assembled in the

Lottery

collection, innocent young women encounter an eerily seductive figure named James Harris (modeled on the character in the Child Ballad), who at first appears to be an ordinary person—a boyfriend or a colleague—but sneakily, through a sinister trick of the mind, induces in them a kind of madness. In early drafts of

Hangsaman

, too, the demon is literal: Natalie is visited by a figure she calls Asmodeus, a Hebrew name for the king of demons. “there was a devil who dwelt with natalie; she was seventeen, and the devil had been with her since she had been about twelve,” one of the early drafts begins. “his was the first voice to greet her in the morning, and at night he slept under her pillow. . . . all day he rode on her shoulder, unseen by her mother, and he whispered in her ear.” Asmodeus is an evil alter ego, whispering snide quips about Natalie’s parents and urging her to yield her soul to him. In later drafts the literal demon disappears from the novel and the figure of the detective takes over as Natalie’s inquisitor, plumbing the depths of her guilty heart.

The demon in the mind, Jackson wrote, exploits one’s bad conscience, spinning ordinary worries and grievances into destructive obsession. It is striking that the sources of fear she was still writing about nearly thirty years later are reminiscent of the stresses she suffered as an adolescent: “being someone else and doing the things someone else wants us to do,” “being taken and used by someone else”—in other words, yielding to Geraldine’s (and later Hyman’s) vision for her, which she feared would cause her to lose her own identity. Even words are to be feared: words that unfairly categorize, that criticize, that damage.

AFTER JEANOU’S DEPARTURE, SHIRLEY

spent the next few months in summer school, trying to improve her grades. Her sophomore year started inauspiciously, with an English teacher she had a crush on conspicuously absent from her course schedule. But now her focus was her writing: she had a “glorious” new typewriter and was happy with what she was accomplishing with it. She had reason to suspect that her mother was going through her papers again, especially after Geraldine scolded

her for writing “sexy stories.” (She was living back at home—the Jacksons had moved to a larger house within walking distance of campus.) “I shall have to lock my desk,” Shirley resolved. “I

would

like some privacy.”

Despite Geraldine’s interference, she continued to be productive. “Wrote an allegory which might mean something,” she reported to her diary in September. She was most pleased with a story she called “Idiot”: “The idea is driving me insane, but it’s there—and the story won’t end.” The piece does not survive, but the title suggests that it dealt with a character who was mentally retarded or otherwise deficient—another of the outsider tropes that would later recur in different versions throughout her fiction. Jackson worked up the courage to submit “Idiot” to

Story

magazine, which rejected it. Nonetheless, her confidence in her work continued unabated. “Wrote a play tonight which delights me—it is so

myself

!” she exulted a few weeks later, chiding herself immediately afterward for conceit.

None of the girls in Shirley’s small circle of friends had replaced

Jeanou, especially in terms of intellectual excitement. But she began to date a boy named Jimmie Taylor, whom she had met one night in November at the movies: “very nice, and surprisingly fun—good dancer.” For her nineteenth birthday, he took her to the Peacock Room, a rococo restaurant featuring opulent chandeliers and a live cabaret band. Jackson complained that he was dull, but she enjoyed having a boyfriend to go dancing with. After he stood her up for a date, she vowed never to speak to him again—until the next day, when he showed up at her house with a gardenia to apologize. (She still gave him “what is technically known as Hell,” she told her diary proudly.) Her customary new year’s musings for 1936 show that, unserious as it was, the relationship was interfering with her Harlequin equilibrium. “For people who do not care, life can hold so much of interest and so much of delight, I have discovered. There is a strange charm in feeling not able to be hurt.” But she could not will herself out of emotion. “It is so desperately easy to resolve ‘I will not care,’ and so much easier to break that resolve!”

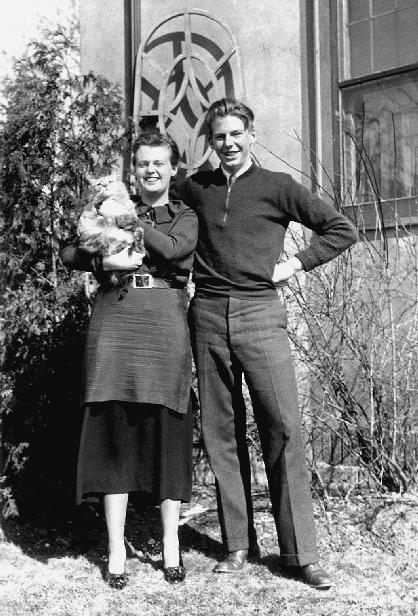

Shirley and Barry Jackson in Rochester, c. 1935.

If the Jacksons’ intention in moving Shirley home had been to keep an eye on her schoolwork, they were not successful. She failed three of her fall courses—biology, French, and psychology—and barely squeaked by in the remaining two, English and archaeology. In the spring, her grades plummeted even lower, and she was put on academic probation. By June, the university had asked her to leave. Later she would say she was thrown out “because i refused to go to any classes because i hated them.”

Jackson certainly did not lack the intelligence to succeed at Rochester. Did she suffer another episode of depression that led to her failing grades? Or was it the other way around—her grades began to slip, inducing her mental disintegration? Regardless, she was deeply demoralized by her failure at college. And living at home could not have helped. Her mother pressured her constantly to find a boyfriend who would become a suitable husband—preferably someone rich who could support her in the style to which Geraldine and Leslie were accustomed, a life of country clubs and ski trips. At the same time, Geraldine continued to be highly critical of her daughter’s figure, her looks, her personal style. She warned Shirley that she would never meet a man unless

she lost weight and dyed her hair. All Shirley’s life, Geraldine had been telling her that she was unsuitable, undesirable, unattractive. Now the University of Rochester had rejected her too. A psychiatrist who treated her in the 1960s would later say that she had her first breakdown during college.

Major depression often emerges in late adolescence. Sylvia Plath—whose novel

The Bell Jar

, which also depicts a young woman’s breakdown, was likely influenced by

Hangsaman—

tried to kill herself for the first time at age nineteen, the same age as Jackson was during much of her second year at Rochester. (Plath, who also struggled with her relationship with a domineering mother, admired Jackson and hoped to meet her during a summer internship at

Mademoiselle

in 1953.) Was Jackson’s depression serious enough that she tried to kill herself, as the memoir quoted earlier suggests? It is certainly possible. She had suicidal thoughts as early as sixteen. Her college diaries reveal that her mental suffering was intense. Back in February 1935, that month of “evil omen,” she called her life “deadening” and wondered, “Will there ever come a break, and will there be any life to jump at the break when it comes?” She did well for several months after Jeanou left, but by November 1935 her “old fears of people” had returned. The following spring she suffered from “nerves and overwrought temperament.” A poem tucked into her 1935 diary is written from the perspective of a person who might be about to jump off a bridge, looking at “the fearful cold waters below.” (Several years earlier, as Jackson probably was aware, the poet Hart Crane had committed suicide by jumping off a boat bound to New York from Mexico.) The story “Janice,” written during her first year at Syracuse University, depicts a girl at a party who casually tells friends that she attempted suicide because she wasn’t able to return to college. In another story Jackson wrote around the same time, a girl tells a male friend about her brush with suicide—she had planned to jump off a bridge:

“you were just going to slip off into the water?” asked victor.

“very softly,” i said.

“with no more than that?” asked victor.

“no more than that,” i said.

“tell me,” said victor, “why didn’t you die?”

“i forgot,” i said. “i went home and wrote a poem instead.”

But it is telling that the girl in Jackson’s bridge story talks about committing suicide rather than attempting it. In “Janice,” too, the girl does not go through with the deed. Talking, or writing, takes the place of action.

On her last day at the University of Rochester—June 8, 1936—Jackson wrote herself a letter, addressed to “Shirlee” and signed “Lee”: the name of a new persona. Lee explains that she is leaving her old self behind: “You don’t mind my outgrowing you, do you?” If she once was suicidal, she is no longer. “I still want to live, as you did,” she writes. “And now I think I know how. . . . Through you, and all the rest in that desk, I have learned to be willing.”

The rest in that desk

—the little black datebooks, the “Debutante” diary, all the pages on which she tried out new writing styles and new characters—were instruments she used to find her voice.

As her classmates returned to campus in the fall, Jackson spent what would have been her junior year at Rochester in her bedroom at her parents’ house, working on her writing. Elizabeth Young, a friend from college who was close to her at the time, recalled that she set herself a strict—and ambitious—quota of a thousand words a day. None of what she wrote then appears to survive. By the spring of 1937, she had resumed her regular social schedule of dances and dinners at the country club—sometimes in the company of Michael Palmer, the son of one of her father’s business acquaintances and the first boyfriend she considered marrying.

As Jackson regained her mental strength, her parents started to worry about her future. Leslie apparently told her that he would send her to any school she chose, as long as she promised that she would “stay there and behave [herself] and graduate.” As a further enticement, he suggested that if she indeed “conducted [herself] like a lady” in college—probably meaning that she stop cutting classes and take her schoolwork seriously—he would let her go to Columbia University

for a graduate course in writing. Geraldine did not support this plan; she wanted Shirley to stay close to home and marry Michael. But Leslie triumphed.

“I wish to further my writing career,” Jackson wrote on her Syracuse application, explaining for a second time why she wanted to attend college. A hundred miles from Rochester, the university was well-known then, as it is now, for its English and journalism programs, as well as for its liberal atmosphere. (Michael Palmer disapprovingly called it “a hotbed of communism and antisocial attitudes”; he was not entirely wrong.) Her family, as usual, did not know what to make of the plan. In a posthumously published sketch, Jackson recalled her teenage decision to become a writer. “Since there were no books in the world fit to read, I would write one,” she resolved. She wrote a mystery story in which any of the characters could potentially be the murderer, and decided at the end to put all their names in a hat and draw one out, “thus managing to surprise even myself with the ending.” She brought the finished manuscript downstairs to read to her family. “Whaddyou call that?” her brother responded. Her father said, “Very nice.” Her mother wondered if she had remembered to make her bed.

Soon their lack of interest would no longer matter. Jackson was about to meet the person who would become her most fervent admirer—and her sharpest critic.

3.

BROOKLYN,

1919–1937

[Modern criticism] guides, nourishes, and lives off art and is thus, from another point of view, a handmaiden to art, parasitic at worst and symbiotic at best.

—Stanley Edgar Hyman,

The Armed Vision

T

HE PHOTOGRAPHER PHILIPPE HALSMAN, RENOWNED FOR

his elegant portraits of royalty, politicians, actors, and other celebrities, pioneered an unorthodox technique. In the 1950s, he began asking his subjects to jump as he took their picture, believing that the moment of the jump communicated something essential about a person that a more controlled facial expression or body language might disguise. “I wanted to see famous people reveal in a jump their ambition or their lack of it, their self-importance or their insecurity, and many other traits,” Halsman explained.

Halsman photographed Stanley Edgar Hyman in 1959 to accompany an article on tragedy that Hyman had written for the

Saturday Evening Post

. In the formal photograph chosen by the magazine’s editors, Hyman holds a smoked-down cigarette in his long fingers; his beard is thick,

his forehead prominent, his eyes dark behind black-framed glasses. He looks the epitome of the serious literary critic. But Hyman’s jump photo tells another story. On the first take, he jumped so high that the frame captured only his feet—not what Halsman had expected from a sedentary scholar. Halsman readjusted the camera and Hyman jumped again. This time Halsman caught him at the very top: eyes squeezed shut, lips twisted in a near grimace, knees drawn up beneath him. He might be an eccentric millionaire about to do a cannonball, fully clothed, into a swimming pool. Or a guest at a Jewish wedding throwing himself

into an especially spirited kazatsky, a dance Hyman knew and loved. Or simply a man at a moment of intense concentration, determined to put his whole being into his act. He would not be satisfied with anything less than the best jump he could possibly achieve.