Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (12 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

Stanley Edgar Hyman by Philippe Halsman.

“

MY ANCESTORS WERE

normal people, I being the only insane person in the family,” fourteen-year-old Stanley Hyman declared in a summary of his life to date. Unusually for a Jewish writer of his generation, he was a second-generation American: both his parents were born in the United States. His paternal grandfather, Louis Hyman, was part of the third major wave of Jewish migration from Europe to the United States, emigrating from Lithuania to New York in the late nineteenth century to avoid conscription in the czar’s army. Stanley would say that his grandfather had been a bootlegger, which “paid, even in Russia.” After Louis’s arrival in the United States, he initially worked as a pack peddler in the South, where, as an observant Jew, he restricted himself to a diet of roasted peanuts to avoid food cooked with lard. After he had saved enough money, he bought a pushcart and a site for it on the Lower East Side and sent for the rest of his family.

Stanley’s father, Moe (short for Moises), was born in 1891 and grew up among the tenements of Orchard Street, together with four siblings, in circumstances similar to the portrayal of immigrant Jewish life in Henry Roth’s novel

Call It Sleep

—so similar, in fact, that Stanley would later tell stories he said (and probably believed) were about his parents that actually came from the novel. Eventually Louis established a small paper-manufacturing business, L. Hyman and Sons, in which Moe would join him. Decades later, L. Hyman and Sons would provide Moe’s son and daughter-in-law with the yellow copy paper on which they typed nearly all their work.

In 1915, Moe married Louisa (Lulu) Marshak, the youngest of seven sisters. The couple were first cousins, but the two branches of the family were temperamentally very different. Lulu’s father, Barney Marshak, also from Lithuania, was a Talmudic scholar, a “sensitive, idealistic, and deeply religious soul” who traced his lineage, according to family

lore, back to the Ba‘al Shem Tov, the rabbi who founded the mystical Hasidic movement. Like Geraldine Jackson, Lulu found it important to maintain certain standards: she wore a corset and stockings whenever she left the house and prided herself on the condition of her home. “She was one of those women who had to rush out and clean the ashtray every time someone flicked an ash into it,” Phoebe Pettingell, Stanley’s second wife, would recall. But, unlike Geraldine, Lulu also had a spontaneous, fun-loving side, especially later on, with her grandchildren. When twelve-year-old Laurence Hyman became enamored of jazz, he begged his grandparents to take him to the Copacabana, a Manhattan nightclub, to hear Louis Armstrong. Moe refused. Not only did Lulu take Laurence, they went three hours early and got the best table in the house. Laurence never forgot it.

Stanley, Moe and Lulu’s first child, arrived on June 11, 1919. “It has not yet been declared a National Holiday,” he would write as a teenager, tongue only partially in cheek. “Someday it will be.” Before becoming pregnant with Stanley, Lulu had suffered multiple miscarriages, and Stanley arrived prematurely, perhaps as much as several months early. A tiny, weak infant, he came down with a case of pneumonia so serious that he was not expected to live. The dramatic circumstances of his birth and infancy contributed to his sense of himself, from a very early age, as exceptional: a brilliant dynamo to whom the usual rules, even those having to do with birth and death, did not apply. This self-assessment was not altogether inaccurate. Stanley would grow up to become one of the most important critics of his generation; he published

The Armed Vision

, a major work of literary scholarship, before he turned thirty.

Like Saul Bellow and Bernard Malamud, two of the other major Jewish writers of his cohort, Stanley grew up with a domineering father and a weaker, emotionally fragile mother. In their own way, Moe and Lulu Hyman were as challenging a set of parents as Leslie and Geraldine Jackson—and they had just as difficult a time appreciating their unusual child. Stanley described his father as “a willful, independent, unemotional man, bigoted in his opinions” and uninterested in discussion or debate. “A man who wanted no affection, and who possessed none to give back in return, he bred me to the same stern pattern. . . .

I became a smaller edition of my father . . . as tight-lipped and unsentimental a little boy as ever grew.” Walter Bernstein, a close childhood friend of Stanley’s, remembered Moe as “peremptory,” with “a tough demeanor.” Once, accompanying Stanley on a visit to Moe’s paper business on Varick Street in SoHo, then Manhattan’s industrial district, Walter absentmindedly picked up a paper clip from Moe’s desk to fiddle with. Later, standing on the subway platform, he realized with horror that he was still holding the paper clip, and worried that Moe had seen him take it and would think he had intentionally stolen it. “I was scared of him,” Walter admitted. Stanley, too, cultivated a tough-guy persona. Walter recalled a favorite game of his: “He would say, ‘I’ll let you hit me in the stomach as hard as you can if you let me hit you in the stomach as hard as I can.’ I never let him.”

Lulu, for her part, was asthmatic and likely depressive. Despite her shortcomings as a mother, Stanley felt protective of her. “I invariably took her side in her recurrent battles with my father, and yet it was somehow my father that I consciously aped and tried to be like,” he would later reflect. An uneducated woman, she saw her brilliant, precocious son as something of a changeling, an alien. She was once called into school to hear the results of Stanley’s IQ test: he had scored 180. “So?” Lulu responded. She was “frightened of his intelligence,” Pettingell remembers. Lulu doted instead on her younger son, Arthur, a more conventional child with whom she was apparently able to bond more firmly. Stanley was fiercely jealous of their close relationship. But the fact that his own mother did not quite know what to do with him must have confirmed his conviction that he was a superior being.

By the time Stanley reached elementary school, Moe and Lulu had left behind gritty Manhattan for the tree-lined streets of Midwood, a newly developed middle-class Brooklyn neighborhood filled with rambling Victorian one- and two-family houses. Malamud, five years older than Stanley, grew up in the same area and attended the same high school, Erasmus Hall, but the two writers would not meet until Malamud began teaching at Bennington, in 1961. Norman Mailer, several years younger, grew up in nearby Flatbush but went to Boys High in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Then, as now, Borough Park was home

to a substantial community of Orthodox Jews. Stanley attended P.S. 99, the neighborhood elementary school, “full of savage little children or grandchildren of immigrant Jews, like myself, fiercely competing to get ahead in the world through education, to become dentists or accountants or pharmacists or whatever.” Many years later, teaching at Bennington, he delighted a student who had graduated from the same elementary school by singing the school song. June Mirken, who went to grade school with Stanley and later became close friends with him and Shirley at Syracuse University, recalled that he raised his hand so frequently in class that the teacher had to tell him to give the other students a chance. Stanley, more mildly, commented that he “competed with great success.”

Religion was important to Moe and Lulu, as it was to most American Jewish families of their generation. The family observed rituals such as keeping kosher, and Lulu would eventually teach her daughter-in-law how to cook potato kugel and the other comfort-food staples Stanley grew up with; Shirley took particular pride in her potato pancakes, and she once tried to structure a story around the kugel recipe. Stanley and Arthur were both bar mitzvahed at Congregation Shomrei Emunah, an imposing Romanesque Revival synagogue on Fourteenth Avenue,

walking distance from the Hyman home. Even though Stanley detested Hebrew school and never managed to learn much of the language, he carried out his religious obligations with the zeal he brought to all his youthful passions. On Yom Kippur one year, he fasted until he fainted. At age sixteen he collected so much money for the Jewish National Fund to buy land in what was then Palestine that he received an award. In college, he formed an important friendship with Jesse Zel Lurie, one of the first Jewish journalists to report from Palestine.

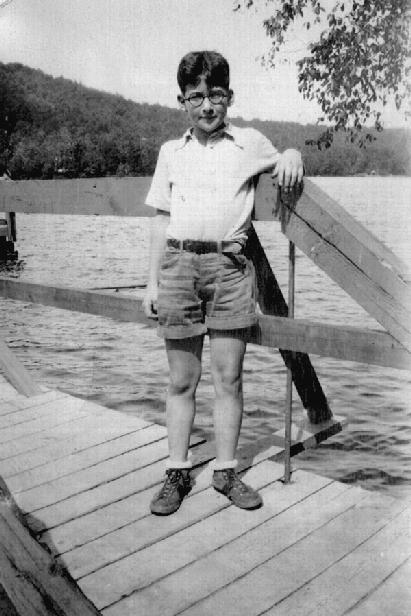

Stanley on vacation, age ten.

But Stanley would later say that he was a “militant atheist” by the time he reached high school, which made him as much of an outcast in his family as Shirley was in hers. His atheism had its roots in the humanistic studies he began to pursue at a very early age, both independently and with a series of mentors to whom he looked for the intellectual stewardship his parents could not provide. Shirley had to wait until Jeanou’s arrival, during her freshman year of college, to find an intellectual guide, but Stanley discovered the first of his as early as age eight: a girl named Berenice Rosenthal whose family lived upstairs from the Hymans. Six or seven years older, with an interest in philosophy, she instilled in him a disdain for mysticism and a love of empirical truth. Berenice loved to tell the well-known anecdote about the French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace, who, when asked by Napoleon why he had written a treatise on the universe without once mentioning God, answered proudly, “I had no need of that hypothesis.” Stanley would later credit her with having led him away from the religion of his childhood: he would eventually come to understand the Bible as no different from any other system of mythology. Berenice, he said, “freed my mind from all the bigotry and narrowness of my home environment, made me question everything I believed or respected, taught me both to think and to evaluate. Entire new vistas opened up for me under her tutelage: microbes, hypnotism, the theater, mathematics, all of science [and] of truth-seeking.” Nearly thirty years later, when Stanley discovered his daughter Sarah, then seven years old, on her knees praying to Jesus, he sent her to her room and made her read Thoreau. At the breakfast table, he sometimes made his children recite the phrase “Jesus is a myth.”

The educational role Berenice played in Stanley’s life was next filled

by Gil, a camp counselor he met the summer before he entered high school. While the other boys were playing baseball or swimming, Stanley and Gil sat in their tent, talking about art, literature, music, and natural history. Stanley, short and heavily nearsighted, had never been athletic; now, he joked, he “became stagnant physically.” But his mind was active. Gil introduced him to Lucretius’s

De Rerum Natura

and to Baudelaire. “For the first time in my life I began really to read, omnivorously and far over my head,” Stanley recalled several years later. Gil also demonstrated a type of masculinity far different from the model his gruff father presented. “He talked me out of thinking that poetry was only for ‘pixies,’ and convinced me that there were other men besides himself who used words like ‘beauty,’ ‘rapture,’ and ‘sublime’ without being ashamed.” At camp, Stanley hunted for mushrooms alone in the woods; back in New York, he made friends with the curators of the Bronx Zoo reptile house. He would later astound a Bennington colleague with tales of putting a praying mantis and a nightcrawler together in a milk bottle so that he could “watch—with dazzling cruelty—the ensuing battle.” When he and Shirley briefly lived in rural New Hampshire in the early 1940s, Stanley had an opportunity to rekindle his interest in the natural world, collecting snakes and turtles. The works of Darwin, which Stanley read in their entirety, would form one of the four pillars of

The Tangled Bank

(1962), his nearly five-hundred-page magnum opus.

While Stanley’s childhood was intellectually rich, the Hymans often struggled financially, downsizing more than once to a smaller home. It was not easy to run a small paper business during the Depression, when the average income of the American family fell 40 percent. In contrast to the lush estates and bustling car dealerships of Burlingame, California, where the rich were able to avoid the worst of the Depression, Hoovervilles popped up all around New York, from a former reservoir in Central Park (now the Great Lawn) to the Brooklyn waterfront. “One got used to seeing older men and women scrounging in garbage cans for their next meal,” Malcolm Cowley, an editor at

The New Republic

and soon to become an acquaintance of Stanley’s, wrote in his memoir of those years. During the winter of 1931–32, New York families received

an average of $2.39 per week in relief funds. For most of Stanley’s childhood, at least one aunt or uncle lived with the family, and he would later say that he grew up surrounded by affectionate female relatives. Moe’s father and uncle offered material assistance, but at one point the Hymans resorted to selling their furniture to raise money. Moe also had a gambling habit. “His idea of a good time was to hang around on the street outside the barbershop with the other men and talk about baseball and place bets,” Laurence Hyman says. Eventually, the family’s situation was stable enough to allow for regular summer vacations at the Borscht Belt resorts frequented by Jews of their era. But Stanley never forgot those years of financial anxiety.