Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (14 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

But in other ways Stanley was significantly less progressive. Many years later, he would reportedly say he did not believe it was possible for a woman to be raped. No matter how adamantly they might protest, he claimed, women wanted to be forced into sex, and “ultimately their excitement made them receptive.” This line of thinking was not unusual for men of Stanley’s era, but—influenced later by his deep reading into Freud—he may have taken it further than most.

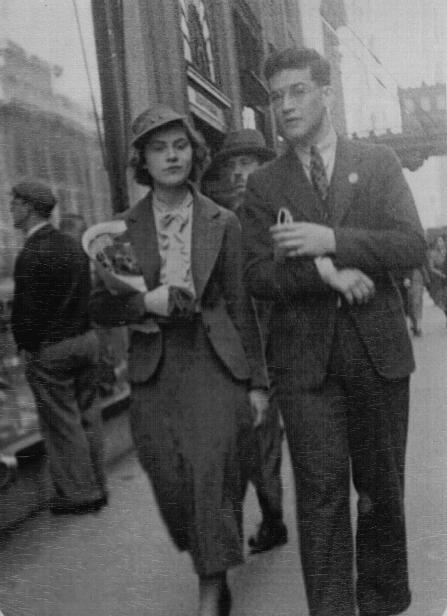

STROLLING ACROSS THE BROOKLYN BRIDGE

one night in the summer of 1936, shortly before he left for Syracuse University, Stanley had an epiphany. On his arm was Elsa Dorman, a “small, round, red-haired girl, of the type described in novels as ‘pert,’ ” whom he had recently met and was trying desperately to impress. Several years older, Elsa was one of the first Communists he had ever encountered, and the two of

them spent much of that summer, on the eve of the Spanish Civil War, discussing political theory. Despite his atheism, Stanley was not an easy convert: his innate individualism and skepticism of any kind of intellectual conformity made him an unlikely Communist. But that night on the Brooklyn Bridge, he suddenly was convinced. Perhaps the lights of lower Manhattan reminded him of his own family’s modest beginnings in the tenements; perhaps the view onto the industrial warehouses of Brooklyn’s Vinegar Hill brought home the reality that the problems of the worker were not limited to Europe; perhaps it was just the inherent romance of the bridge on a warm summer night that swayed him. The next day he signed up for the Young Communist League (YCL).

Stanley with Elsa Dorman, c. 1936.

Stanley’s conversion took place just as a growing number of writers and intellectuals were becoming aware of the possibilities for revolution, both politically and creatively. In the traumatic Depression years, many came to see the capitalist system as irremediably broken, its demise taking with it their hopes for progressivism. Literary journalist and social critic Edmund Wilson, who traveled around the country in the early 1930s reporting for

The New Republic

on the condition of miners and other workers (his essays were collected as

The American Jitters

in 1932),

initially called for American radicals to “take communism away from the Communists,” though he soon came to embrace Marxism. (Later Stanley would memorably skewer Wilson—for his critical method, not his political beliefs—in the pages of

The Armed Vision

.) But many intellectuals decided either to cooperate with the Communist Party as fellow travelers or to join. For some, this youthful moment of idealism had far-reaching consequences.

Malcolm Cowley, a colleague of Wilson’s at

The New Republic

who considered himself a fellow traveler, wondered later why Communist doctrine had appealed to so many writers, especially considering how much it could cost them in terms of their literary freedom. His answer was that, in the face of the Depression, the fight against Hitler, and the Spanish Civil War, communism offered a specific plan for action. That certainly seems to have been what appealed to Stanley. If liberalism was a balm for good intentions, communism offered, in the words of his high school yearbook motto, “intentions charged with power.”

Cowley later joked that “Red Decade” was a misnomer; the years between 1929 and 1939 were merely “tinged with pink.” The Party’s political gains were slow: in the 1928 presidential election, the Communists received around 49,000 votes, a modest increase over their showing four years earlier. But the Party’s influence among writers was disproportionate. John Reed Clubs for radical young writers—founded in 1929 by contributors to

The New Masses

, the leading Marxist magazine—sprang up all over the country “to clarify the principles of revolutionary literature, to propagate them, to practice them.” In Chicago, the future novelist and social critic Richard Wright got his start after wandering into a John Reed Club during an editorial meeting. In New York, Cowley found himself summoned to the club’s headquarters in December 1932 to discuss an article he had written for

The New Republic

about a hunger march on Washington. Two of the men who criticized his piece, Philip Rahv and William Phillips, would soon found

Partisan Review

, which—after shedding its Communist Party connections—became the dominant highbrow cultural magazine in the United States from the 1940s through the 1960s.

More than two hundred politically engaged intellectuals descended

upon New York’s Mecca Temple (now New York City Center) and the New School for Social Research for the first American Writers’ Congress in April 1935, a year before Stanley’s political awakening. The call for delegates was written by Granville Hicks, literary editor of

The New Masses

. “He wrote in English, unlike many of his colleagues,” sniped Cowley, who signed the call along with Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Langston Hughes, and numerous other writers. “Hundreds of poets, novelists, dramatists, critics, short story writers and journalists recognize the necessity of personally helping to accelerate the destruction of capitalism and the establishment of a workers’ government,” Hicks wrote. “A new renaissance is upon the world; for each writer there is the opportunity to proclaim both the new way of life and the revolutionary way to attain it.” Delegates to the congress formed the League of American Writers, which would join the International Union of Revolutionary Writers in the struggle against fascism.

The most controversial speech of the congress was delivered by literary critic Kenneth Burke, a pioneer of language-based textual analysis who would soon become Stanley’s intellectual hero and close friend. Burke’s paper analyzed the semiotics of revolutionary language, arguing that if the American Left wanted to appeal to a broader swath of the public, it ought to substitute the term “the people”—more in keeping with American values—for “the masses” or “the workers.” He also argued that this change would benefit the proletarian novel, of which the examples in English thus far had been uninspired. Burke was denounced as a traitor: to suggest that the Left should appropriate capitalist discourse was heretical. The fact that proletarian literature was read only by the intelligentsia rather than by workers or non-Marxists—a problem Stanley would take up a few years later—was not addressed by anyone else at the conference.

By the fall of 1936, when Stanley arrived at Syracuse, news of the Moscow show trials—Stalin’s first effort to purge and execute Trotsky supporters and other dissenters—was beginning to roil the Party’s American devotees. Many writers who had previously been sympathizers, including Wilson and the circle around

Partisan Review

, distanced themselves from the Soviet government. The second American Writers’

Congress, held in June 1937, abandoned the open call to revolution and instead endorsed the broad alliance against fascism known as the Popular Front. Stanley, along with Cowley and the others in the League of American Writers, initially toed the Stalinist line, denouncing Trotskyists as traitors. But in true Jewish style, Stanley admitted to having “constant doubts,” scouring the works of Marx for errors and inconsistencies and remaining deeply skeptical about the Party as a monolithic institution.

Nonetheless, the YCL provided him with an instant social life in college. Florence Shapiro, an art student from Queens, recalled one of the Party’s methods for helping young Communists find one another: before she got to Syracuse, she was given half of a Jell-O box and was told to find the person with the other half, who would be “on the same wavelength.” That person turned out to be Stanley, and the two became friends: she found him “a typical Brooklyn intellectual . . . with a fantastic sense of humor.” A senior became his political mentor and helped him discover a knack for organizing: he was soon distributing leaflets and addressing meetings of a group of steelworkers in Solvay, a suburb of Syracuse. The summer after his sophomore year of college, shortly after he and Shirley met, he took a job working at a paper mill in rural Massachusetts that supplied his father’s business. His goal was to live among the workers, doing manual labor, in order to understand the conditions of their lives—and he was serious enough to go through with it.

At Syracuse, Stanley also had his first encounter with Marxist literary criticism, which was to shape his method of interpreting literature well beyond his college years. The professor who influenced him most deeply was Leonard Brown, who had begun teaching at the university in 1925, when he was only twenty-one. Brown devoted his career to teaching rather than publication; his books are few, but many of his students would remember his influence as formative. His innovation was to teach the ideas of Darwin, Marx, Freud, George Berkeley, Albert Einstein, and anthropologists such as Bronisław Malinowski, Franz Boas, and Margaret Mead alongside the touchstones of modern literature, which he believed had gravitated toward the “sociological position.” During the mid-1930s, Brown was briefly fired for introducing

dialectical materialism into his classes; after a popular outcry, the university quickly reinstated him, and from then on he was allowed to teach whatever he wanted. Brown also brought Burke to lecture at Syracuse several times later in the decade; Stanley would first encounter him there in 1939. While Brown favored a Marxist, scientific approach to literary study, he did not force it upon his students. “What I am attempting to teach,” he told them, “is a method of criticism, not a body of personal beliefs about writers or a ‘view’ of literature.” Stanley’s copy of Brown’s syllabus for the course Main Currents in Modern Literature: 1870–1939—a single-spaced, nine-page reading list in world literature and social thought—is covered with his own additions and annotations. The roots of

The Tangled Bank

extend to this course.

Stanley’s infatuation with communism did not continue beyond his college years. If he suffered a specific moment of disenchantment, to parallel his epiphany on the Brooklyn Bridge, he did not mention it in his writings. More likely, as World War II progressed and Stanley began working at the thoroughly apolitical

New Yorker

, he simply grew estranged from the Party, as did so many other intellectuals. Remarkably, unlike some of his friends, he never suffered any consequences for his youthful political activities. Stanley’s last known Communist affiliation was with the League of American Writers in 1941, as that group’s political stance shifted to advocate American entry into World War II after Germany’s invasion of Russia. From then on, literature would be his only cause.

4.

SYRACUSE,

1937–1940

i want you more than anything in the world and you needn’t imagine that anything you say or do is going to stop me from getting what i want, and you can’t even stop me from wanting it.

—letter from Shirley Jackson

to Stanley Edgar Hyman, summer 1938

“

I

WAS IN THAT FIRST SWEET BOHEMIAN STAGE WHERE ALL LIVING

artists are Artists, and everyone who is pursuing his happy anonymous artistic way through college is a potential satellite,” Jackson later recalled of her early days at Syracuse University. When she arrived there, in September 1937, the school was still relatively small—it would see exponential growth after World War II. Dramatic buildings clustered around a central quad at the top of a hill, including Crouse College, a multistoried Romanesque Revival building, and Hendricks Chapel, modeled after Rome’s Pantheon, with a pillared façade and a dome. Unlike at the University of Rochester, men and women attended classes together, but their living quarters, of course, were separate. For most of her time at Syracuse, Shirley lived in Lima Cottage, a dormitory for about fifty women at 926 South Crouse Avenue.

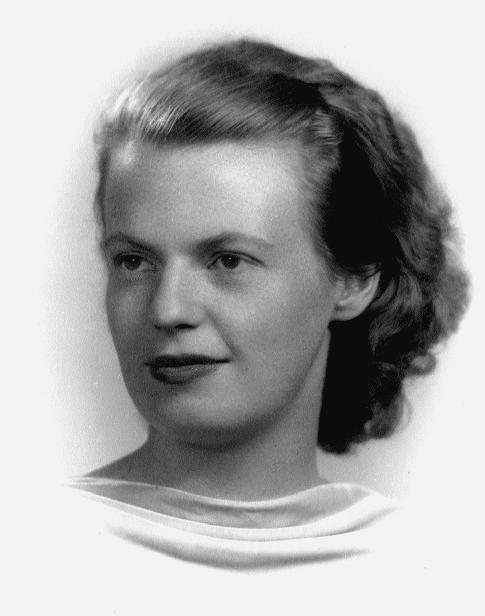

Shirley Jackson’s college yearbook photograph.