Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (38 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

The Armed Vision

was finally published on May 24, 1948. The jacket copy, written by Weinstock, hailed it as “an important publishing and literary event . . . a critical book of major importance, a book over

which rivers of ink will eventually be spilled.” But Hyman’s experience with Knopf had left him demoralized. Even the minor details rankled, especially the fact that his book jacket didn’t include an author photograph or biographical information (which “makes the author feel like an author,” he wrote pathetically to Weinstock). Instead, the space was used to advertise other Knopf books that he happened to dislike. “The literary future I see under this contract is three more books, say the next ten years, in peonage, with the advance for each book whistled past my nose and applied to styling charges, index fees, reset costs, etc., to the accompaniment of nasty notes and bills,” he lamented. “Better to languish unpublished, say I.” He didn’t feel like an author. He felt betrayed.

The critical reaction did little to soothe his bruised ego. Weinstock had gotten mixed results in his quest for blurbs: Wallace Stevens had commended the book as “exciting from beginning to end,” but the critic Mark Schorer, whom Hyman had elsewhere called a “narcissus,” wrote back that he was “unable to lift my gaze from the pool.” In his reader’s report, Tindall had predicted the difficulty of generating positive publicity for

The Armed Vision

, since just about every critic who might write about it was savaged in its pages. “Kenneth Burke cannot review the book for every journal,” he wrote snidely. (Weinstock prefaced his requests for blurbs with the apologetic note, “I feel certain that whether you like this book or not you will find it vastly interesting.”) Alas, Tindall was right. The book’s obstreperousness would have been hard to take from anyone, but it must have seemed especially threatening coming from Hyman, a Brooklyn Jew pitting himself against a generation of WASP literary scholars. When Saul Bellow, a decade earlier, announced his intention to do graduate study in English literature, the chair of his department at Northwestern University discouraged him with a blatantly anti-Semitic remark: “You weren’t born to it.”

A few of the early notices were positive: W. G. Rogers, whose syndicated column “Literary Guidepost” ran in newspapers all over the country, praised Hyman’s “brilliant display of scholarship . . . cogent thinking . . . [and] vigorous writing.” Another reviewer called it “distinguished” and “explosive.” But Joseph Wood Krutch, a drama professor

at Columbia whose biography of Poe had earned a negative mention in

The Armed Vision

, set the tone for much of what would follow in a lengthy piece in the

New York Herald Tribune

on June 20. Krutch’s review betrays a bizarre hostility to criticism in general: “One lays down [the book] with the bemused conviction that . . . the function of the poet is merely to provide some raw material upon which the critics can fling themselves,” he wrote. In his view, Hyman was a parasite eating away at a far more worthy set of hosts.

Hyman’s own publications were no kinder to him. In

The New Republic

, John Farrelly called the book’s goal of developing a scientific approach to criticism “questionable” and its evaluations “arbitrary.”

The New Yorker

, in a brief, unsigned review, judged Hyman’s writing “uncomplicated and often witty” but his conclusions “marked by an almost breathless irresponsibility and lack of judgment.” (The next review praised a new critical anthology, edited by Hyman’s nemesis Schorer, as “thoughtfully planned and instructive.”) Brendan Gill sent a nice note, but admitted that he had read only to

chapter 4

. Hyman’s old friend Louis Harap lectured him that his understanding of Marxist criticism was inadequate.

Despite his obvious disappointment, Hyman managed to have a sense of humor about the reaction. A cartoon he preserved in the scrapbook shows a man surrounded by a mountain of books and magazines as his wife holds up a tiny clipping: “Look, George, a favorable review!” He repeated with amusement a report that the Yale Co-op, misconstruing the title, had shelved the book under Military Affairs. And he treasured the complimentary notes he received from friends and colleagues. But the criticism stung him—he complained to Ellison of Krutch’s “nasty petulance”—and so did the low sales. During the first six months after publication,

The Armed Vision

sold only 1500 copies, grossing just over $700, which left Hyman nearly $250 still to recoup. “Aside from being up against a financial wall, I have no complaints,” he wrote wryly to Jay Williams, who responded with another loan. He did not receive his first royalty check until September 1950. For the next two years, the book sold only a few hundred copies a year, earning Hyman less than $300 in royalties. In February 1952, Knopf announced its intention to melt the

plates, taking the book officially out of print. Hyman would not publish another work of literary criticism until 1961.

AS

THE ARMED VISION

limped along, “The Lottery” sprinted ahead. It was anthologized immediately in the

Prize Stories of 1949

as well as

55 Short Stories from the New Yorker

(1949), a volume celebrating the magazine’s twenty-fifth anniversary. Vladimir Nabokov marked the table of contents in his copy with a grade for every story: “The Lottery” was one of only two that he deemed worthy of an A. (He gave an A+ to “Colette,” his own story in the volume, as well as to Salinger’s “A Perfect Day for Bananafish.”) The composer Nicolas Nabokov, Vladimir’s cousin, expressed interest in making “The Lottery” into an opera, with Jackson writing the libretto: “We may be the Gilbert and Sullivan of this generation,” she joked. In March 1951, a version of “The Lottery” was broadcast on the NBC radio program

NBC Presents: Short Story

. “An ugly story, ‘The Lottery,’ ” wrote Harriet van Horner in the

Washington Times

. “But how brave of radio to do it!” The story was also adapted for Albert McCleery’s television program

Cameo Theater

. Rod Serling, creator of

The Twilight Zone

, later recalled that the TV show made the “anti-prejudice message much more pointed.”

The story was anthologized for students as early as 1950, and it is still included in textbooks for high school and college English courses. It has been used to teach medical students how to evaluate the ethics of scarce resources (whether to allow an elderly patient to occupy a valuable intensive-care bed, for instance) and to dramatize questions of self-interest for high-school students (one teacher randomly awarded one student a grade of 0 on an assignment and gave all the others a grade of 100 to see how they would react). After coming to power in 1948—coincidentally, the same year “The Lottery” was published—the government of South Africa included the story on a list of banned books along with Lillian Smith’s

Strange Fruit

and Richard Wright’s

Native Son

, among others. Hyman would later say that Jackson was proud of this distinction: “she felt that

they

at least understood the story.” There are Marxist, feminist, symbolic, and religious interpretations. One scholar

analyzed the method of selecting the victim and determined that some villagers actually have a greater chance of being selected than others: since the first drawing selects the family and the second selects the particular victim, villagers from small families are at a disadvantage.

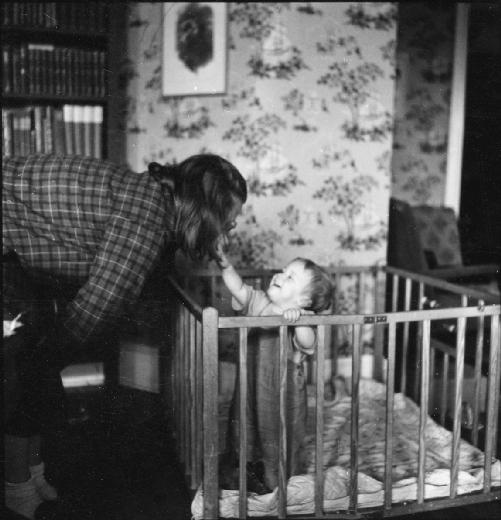

Jackson reading “The Lottery” during a lecture in Michigan, July 1962.

Even though her earnings from permissions fees were substantial, Jackson eventually grew annoyed that “The Lottery” was reprinted much more often than anything else she wrote. She worried, not without justification, that she might become known for that story and nothing else—which for many years after her death was indeed the case. At one point, she asked her agent to raise the permissions fee to encourage editors to “let the poor old chestnut rest for a while.” The only difference the price hike made was to bring in more money.

Grudgingly, Jackson agreed to record “The Lottery” for Folkways Records in 1959. Along with her recording of “The Daemon Lover,” on the B side, it is the only recording of her voice that still exists. The agoraphobia of her late years had not yet begun, but she preferred to avoid New York City if possible, and refused to make a special trip to do the recording. Laurence, then a technically adept senior in high school, did it for her on a reel-to-reel recorder at Bennington. Jackson, nervous, brought

along a glass of bourbon; the clink of ice cubes in her glass is occasionally audible. Her voice is low, with the slightest hint of an English affectation. She reads the story calmly, almost without expression. A sharpness enters her tone only when Tessie Hutchinson begins to speak. Jackson’s voice ascends shrilly as she reads the lines: “It isn’t fair, it isn’t right.” She gives the final line of the story a curious inflection: “And

then

they were upon her.” Like the pointed collar around the throat of the dog Lady in “The Renegade,” the recording cuts off abruptly before her voice has a chance to die out, making the last line sound like a question: And

then

they were upon her? The irony is audible. They have been upon her all along.

9.

NOTES ON A MODERN

BOOK OF WITCHCRAFT

THE LOTTERY: OR,

THE ADVENTURES OF

JAMES HARRIS

, 1948–1949

[S]he was running as fast as she could down a long horribly clear hallway with doors on both sides and at the end of the hallway was Jim, holding out his hands and laughing, and calling something she could never hear because of the loud music, and she was running and then she said, “I’m not afraid,” and someone from the door next to her took her arm and pulled her through and the world widened alarmingly until it would never stop and then it stopped with the head of the dentist looking down at her. . . .

She was back in the cubicle, and she lay down on the couch and cried, and the nurse brought her whisky in a paper cup and set it on the edge of the wash-basin.

“God has given me blood to drink,” she said to the nurse.

—“The Tooth”

F

OUR MONTHS AFTER “THE LOTTERY” WAS PUBLISHED, JACKSON

arrived at the hospital to give birth to her third child. As she would tell it, the clerk who admitted her asked her to state her occupation. “Writer,” she answered. “Housewife,” the clerk suggested. “Writer,” Jackson repeated. “I’ll just put down housewife,” the clerk told her.

This story appears in a magazine piece Jackson called “The Third Baby’s the Easiest,” a hilarious account of labor and delivery that would later be included in

Life Among the Savages

. Comedy aside, it perfectly illustrates the dilemma of her Janus-like dual identity—a dilemma that would become even more pronounced as her books achieved greater success and her fame grew. She was Mrs. Stanley Hyman: housewife, PTA member, faculty wife, mother to Laurence, Joanne, and now Sarah. And she was Shirley Jackson: the author, when she wrote that piece, of one finished novel, numerous short stories, and a forthcoming

collection that included the literary sensation of 1948. That tension would never be resolved; if anything, it would grow more pronounced over the coming years. But Jackson also would grow skilled at manipulating it—and at using it in her fiction to illuminate the problems that defined women’s lives of her era.

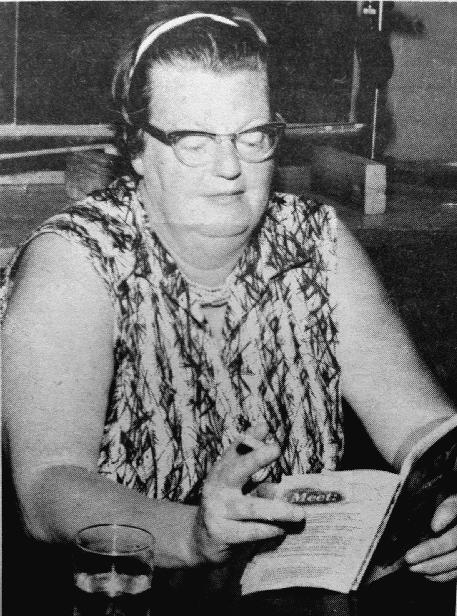

Jackson in North Bennington, late 1940s.