Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures (18 page)

Read Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures Online

Authors: Sir Roger Moore Alec Mills

The saga was now in full swing. Oliver Reed was next, threatening to walk off the film, claiming that he could not stand working with Ryan’s replacement, another American actor allegedly recommended by Candice Bergen. ‘All change!’ a wag remarked, with Mitchell Ryan being recalled to the set, probably on a better deal this time, with his family now in close attendance.

With all this uncertainty going on I expected to be next in line for the hatchet – heads or tails time – however, I managed to struggle on through to the end of this dreadful ordeal, completing my punishment for not resigning as Michael had done in the first place. As luck would have it, Michael would have hated working with this director; his concerns with the script had protected him from this awful person. Now I was left with a sad experience to reflect on – possibly something I would need to learn from.

As filming eventually got back to normal there was one more questionable moment as we moved to Almería. The production company hired an aircraft to take the unit and equipment to the new location. Oliver Reed, Don Medford and the minor roles joined us on the trip, but for reasons known only to himself, the producer decided to travel by road. The flight went well enough until we were making our final approach to the airport, when the starboard engine suddenly caught fire. Through the windows we could see flames pouring from the engine, made worse as the propeller was still working, fanning the burning oil over the wing – a fireball in the making! Although there were no immediate signs of panic on board you could be sure our heartbeats were racing faster than normal; fortunately the engine’s fire extinguisher still worked and the pilot managed to land on one engine.

While filming

The McKenzie Break

we found ourselves on location in Kensal Green Cemetery, which was a little scary as I found myself standing in a grave only yards from where my elder brother Alfie had been laid to rest in 1938. My expression clearly explains this moment with director Lamont Johnson.

A posed photograph for the album! The camera crew included Ron Drinkwater (focus puller), Michael Reed (cinematographer), myself (operating) and a young Malcolm Mackintosh (clappers) standing behind Michael.

It was later established that the aircraft was on its last flight before being scrapped. The obvious conclusion was that it had been rented out cheaply to the production company. When we heard this, you could be sure that the matter would not end there; Oliver Reed personally threatened the demise of the producer, although by the time he finally arrived in his car Ollie had calmed down. After the aeroplane incident the unit seemed to receive more respect and I do not recall seeing the producer after that episode – he suddenly disappeared from the scene without a trace.

The Hunting Party

was about abduction. Outlaw Frank Calder (Oliver Reed) kidnaps Brandt Ruger’s wife (Candice Bergen) and Ruger (Gene Hackman) forms a posse to go after them, which of course ends with the predictable bloodbath. The supporting cowboys were recognisable names from a past era, probably cast more for their horse-riding skills. Although L.Q. Jones, Simon Oakland and Mitchell Ryan were now visibly slower on the draw, they were still happy to go down memory lane as we sat around the crackling fire at night, listening to the spitting wood and reliving memories past.

Yep – happy days, returning to the past!

There is a strange excitement in a profession where you can never be sure where the next challenge might come from, dealing with many egos and trying to win over new faces, or perhaps unpleasant people to work for. Be that as it may, fresh connections would always be useful, even if they sometimes left a bad taste in the mouth.

My next challenge would bring an entirely different problem to the last experience. It was the early spring when I returned to the UK and film production remained quiet. Even so, that did not matter: I was just happy to be back in civilisation after the insanity of

The Hunting Party

experience.

The expected rest would not last long. Within days a call came from producer Timothy Burrill, asking me to meet the director of a film soon to start in Shepperton Studios. No name was mentioned and at the time I could not be sure if I would be happy or not working again so soon after my recent experience in Spain. Out of curiosity I went anyway.

It turned out that the next director whom I would be shaking hands with was Roman Polanski, who had lately featured in the headlines around the world and was now here in England to direct

The Tragedy of

Macbeth

. At first I felt uneasy as to how I would handle this very delicate interview, bearing in mind the recent murder by the Manson Family of Polanski’s wife, the actress Sharon Tate. I sat there feeling uncomfortable and ill-at-ease as the director carefully weighed me up, considering me. Would I be the right person for Roman Polanski? This unease would pass after a lengthy interview with the director, who invited me to be his camera operator on Shakespeare’s masterpiece. Once the cross-examination was over it was clear there would be none of that ‘Action – Cut – Over here, boys’ attitude with this director – quite the reverse. Roman Polanski knew precisely what he wanted to see on the screen, down to the smallest detail; get it wrong and you would surely hear from him before being shown the nearest exit.

Shooting

Macbeth

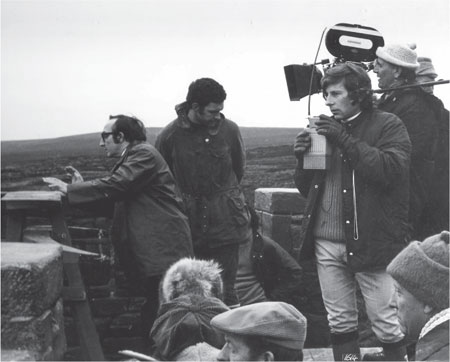

(1975) on location in Snowdonia with Roman Polanski making sure that I understand what he wants – or else goodbye Alec!

The director made it clear that he would be making great use of camera movement to add drama to the subject, which so far was in step with my own thoughts on the matter. Looking directly at me, he added, ‘There will be no limits to the challenge to your skills as camera operator.’

Not knowing exactly what Polanski had in mind, this bothered me. The director’s comments would be repeated and underlined at his first pre-production meeting with all departments coming together.

‘We will be filming direct sound with a BNC camera …’

No problem. However, my comfort would quickly pass when Roman looked straight at me. ‘The BNC camera will be in handheld mode!’

I now understood what Roman meant by ‘no limits’ in challenging my skills. My obvious reaction was to explain the physical impossibility of handholding a BNC camera, but sensibly I decided to remain silent, if only to see where he was heading before the director could point me to the nearest exit! Already I had visions of the muscular camera operator Bob Kindred waiting outside in the corridor in anticipation of my early departure – I had seen Bob hanging around in the canteen earlier – but all became clear when I learned what the director’s definition of a handheld camera was.

Roman’s idea was to install an overhead tracking rail above a large courtyard set in the studio, leaving me to assume that the camera would be coupled to a telescopic harness hanging from the track. Still unconvinced by this, and with the thought of losing the luxury of my geared head – which made operating a camera so much smoother – I could only assume that it would be necessary for me to guide the heavy camera with my hands, with my framing coming from the parallax viewfinder. No way – the idea was ridiculous; I had no chance of winning that battle.

Then again, I reasoned that Roman’s idea could possibly work, but it would depend on how steady the overhead mechanism was and how much control I would have at my end of the apparatus. I certainly had my doubts with all this and at this point it was anyone’s guess what the final outcome would be. I wanted to work for Roman Polanski, so it was important not to sound negative at such an early stage; even so, it would not be easy to tell him that what he was asking was impossible.

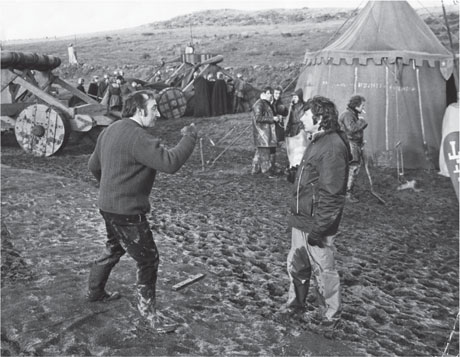

I believe this discussion was about the forthcoming battle sequence.

At the same meeting we discussed the handheld filming on location in Snowdonia. To help with this problem Roman suggested a harness for the Arriflex IIC camera, which would help with the scenes he required. His idea – if not original – involved two strips of 4 x 2 wood resting on my shoulders, strong enough to support the camera with accessories and counterbalanced by the weight of the battery at the other end of ‘Roman’s harness’. Bearing in mind that, like Roman, I am small in build, my concern was more about the overall weight of the equipment, plus the heavy wooden harness, which would not be helpful to my operating. This idea would make it impossible for me to satisfy the standards which the director was demanding from me. Bob Kindred was now back in the frame, but Roman suggested I had time to play around with his idea.

Working from Roman’s basic description, I decided to design my own lightweight alloy harness, made to my own specifications. It was a good deal lighter than Roman’s planks of wood – stronger and easily more manageable – so now the celebrated Mills Handheld Harness was born. My director was suitably impressed, insisting that I also had one made for him. As it happened I had already asked for four to be prepared.