Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures (22 page)

Read Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures Online

Authors: Sir Roger Moore Alec Mills

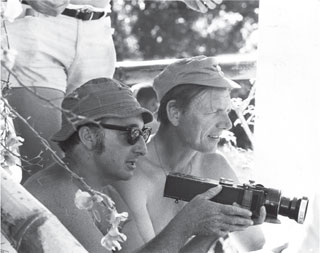

Filming the final battle sequences of

Operation Daybreak

at the cathedral of Saints Cyril and Methodius in Prague. I’m still smiling, so this must have been taken before the result of the Arsenal v. QPR game was known!

With the end of filming and the usual celebrations over we walked to our cars while chatting, with me believing that this would be the ideal time for Harry to make an offer of his next film. It never happened. After shaking hands we went our separate ways, but all was not lost. As I was getting into my car a shout suddenly came from Harry, now some distance away, calling me over to him. With great expectation I hurried to the cinematographer, certain of what he was about to say.

‘Alec, if you hear of a film going, mention my name!’

I stood there, gobsmacked, totally lost for words. Then came take two with the shaking-of-hands bit, which Harry was fond of, before he drove away, never to be seen again. This experience would come as a timely reminder that my chances of moving up the ladder would not come easily, no matter how hard I tried to impress. One learns from experience on many levels.

Now, many years later, I would set out to impress my director, the same Lewis Gilbert. This time, however, I would be Lewis’s camera operator on

Operation Daybreak,

the true story of the assassination of the SS General Reinhard Heydrich, Himmler’s deputy during the war.

Operation Daybreak

would also be an interesting reminder of what our lives would have been like had things worked out differently.

In recent years Lewis had worked with French cinematographers, which would continue with Henri Decae – a pleasant gentleman with a generous moustache and with whom I also enjoyed working. At the same time, I was at a loss to see how I came into this Anglo-French connection. Perhaps Lewis thought it would be to his advantage in having an English-speaking camera operator and my name had fallen out of the hat.

Working with Lewis Gilbert, you could be sure that life was never dull. One of the many memories we shared over the years was our filming of a battle scene in the centre of Prague, which involved a hundred extras dressed as German soldiers. The scene could only be filmed on a Saturday, when the police could seal off all the roads around the cathedral of Saints Cyril and Methodius – the same church where the Czech partisans were hiding after Heydrich’s assassination, where the drama had finally played out fifty years earlier.

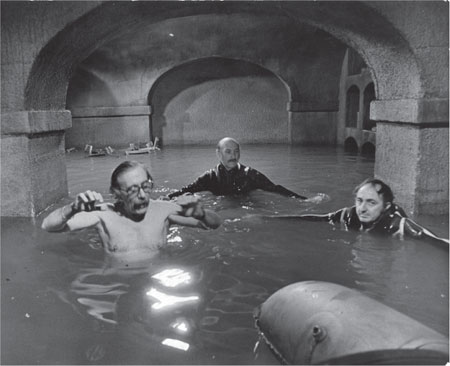

The not-so-comfortable filming of the crypt sequences, where the besieged Czechoslovakian paratroopers eventually commit suicide.

With our German army preparing to storm the building with tanks, machine guns and fire engines, the watching public witnessed the elimination of the partisans trapped inside the church … except that on this particular Saturday there would be a distraction for our director, whose mind appeared to be elsewhere. What would an Englishman like Lewis Gilbert find so distracting in Prague on this particular Saturday afternoon?

Lewis’s beloved football team Arsenal was playing an important match against my team Queen’s Park Rangers, with the game being broadcast live on the BBC’s overseas service. Due to the poor reception, our heads were glued to Lewis’s small portable radio; with five minutes still left in the game the first assistant director arrived to inform Lewis that everything was ready on the set. With that I excused myself and moved away before being hauled back by Lewis grabbing my arm, insisting that I suffer the remaining moments of his pleasure. Arsenal won the battle, whereby I lost a sizeable bet, so making it necessary for Lewis to relish the moment until the final whistle confirmed that we could now get on with the job in hand, leaving me a broken man both in cash and humiliation. Worse still was that I would never hear the end of it from Lewis!

Filming at the train station in Prague – supposedly Berlin – we had to film Adolf Hitler, played by George Sewell, waiting to greet Heydrich, played by Anton Diffring. The plan was for the engine to stop on its prearranged mark so that the carriage came to a halt opposite the Führer. With the scene fully rehearsed, the engine driver backed the train to a reasonable distance from the platform, preparing to enter the station on cue so that Heydrich would step off the train, saluting Hitler in the customary Nazi fashion.

For reasons known only to the engine driver, he decided to change the scene as it had been rehearsed, by passing his mark and stopping a considerable distance down the platform. However, Anton recognised the driver’s error and smoothly moved along the platform towards Hitler. Through the camera I had Hitler on the left of frame wearing his brown coat with swastika armband clearly featured on his left sleeve; as Heydrich approached, the two Nazis came together, only for Heydrich to continue walking straight past his Führer without a second glance and straight past my camera. Anton later claimed that he never recognised Hitler standing there with his toothbrush moustache and dressed in full Nazi uniform – another silly moment we look back on, sharing a quiet smile with each other.

More important was that I had won Lewis Gilbert’s favour with this new relationship developing, where we would soon be working together with a secret agent 007, which would continue long into the future – unlike my efforts with Harry Gillam.

As a camera operator mindful of the need for cooperation to improve the composition in the camera frame, it is necessary to build up relationships with the actors, so making the job easier. However, much depends on their attitude to this, especially with their changing moods where performance was more important. Tact and diplomacy usually paid off; grovelling could be resorted to when all else failed.

One of the many irritations which actors have to live with usually come with early morning calls, perhaps for make-up after having had little sleep – let’s face it, actors are human beings, after all. Whatever their problems, a good camera operator quickly learns to recognise any signs which could leave an actor in a less-than-cooperative frame of mind, making the humble operator’s life difficult – actors’ personal problems are sometimes of little help to the poor soul looking through the camera.

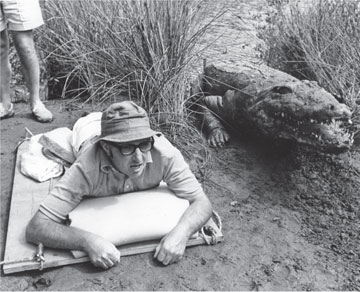

With Michael Reed, lining up a shot on

Shout at the Devil

in the Transkei (1975). The director’s viewfinder is a converted parallax viewfinder from an old BNC camera.

Preparing to shoot Roger Moore’s point of view while being carried on a stretcher. In the background with hands on hip is clapper loader Danny Shelmerdine (not sure if that’s a hat or his hairstyle) and Frank Ernst (first assistant director) holding the loudhailer.

I hasten to add that this daily challenge would never be a problem working with Roger Moore, whom I recognised as the total professional, but now it was time to enjoy the Lee Marvin experience which would test Peter Hunt’s patience to the full on

Shout at the Devil

.

Based on another novel by Wilbur Smith, Roger’s character, Sebastian Oldsmith, was described as a respectable Englishman looking for adventure, while Lee played Colonel Flynn Patrick O’Flynn, an Irish rogue who just happened to have a beautiful daughter Rosa, played by Barbara Parkin. You are aware of my thoughts on Roger Moore, so now let me share my praise of the late Lee Marvin, a down-to-earth actor, a star with few hang-ups – apart from one big problem.

It was no secret that Lee liked his drink; one morning his unscheduled early departure for one of the filming locations gave our anxious director Peter Hunt much reason for concern. However, it would seem that Lee had been unable to sleep and decided to leave early rather than wait for his usual call. When Peter heard of the actor’s early departure it was understandable that he became anxious and worried about the state in which we would find Lee on our arrival, but on this occasion it was a false alarm and the colourful picture I recall was of finding Lee sitting on the dry red earth, with the local villagers sitting around him enjoying the white man’s antics. Lee was as sober as a judge, although more than likely he would have had a couple of cans on the way to the location! With a clear-headed Lee ready for work, Peter was elated, at the same time privately admitting that he could never be sure what would be a good or bad day with our star.

With all of this unpredictability the producer, Michael Klinger, and director came to terms with this very delicate situation, in the end deciding that Peter with his usual tact should be the one to handle any setbacks which might occur as there would be little to gain in upsetting the actor. Even so there were times when Peter had to accept the inevitable, such as one memorable scene when, with time fast running out and the light fading quickly, work had to be postponed until the following morning.

The scripted action was simple. Roger Moore, the expectant father, paces up and down while waiting on the first cries of a newborn baby being delivered; Lee would also pace up and down with fatherly concern for his daughter. Unfortunately, when Lee arrived on the set the next morning he could barely stand, let alone walk! He had been on a bender the previous evening and was in no condition to perform on camera, which came on a day when the actor was in every scene on the call sheet; it was certainly not good news. Head-scratching time – what to do?