Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures (35 page)

Read Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures Online

Authors: Sir Roger Moore Alec Mills

I gave my undivided attention to

Hot Target

as my confidence grew by the day. I was grateful for Denis’s help in collecting another valuable credit as cinematographer. It must be said that the combination of lighting and camera operating did not work for me; my concentration was now more with my lighting. Combining the two positions slowed down Denis’s plans with his tight schedule, let alone the complications of the dreaded black set that was on the horizon. We both realised that it would take time to get right – not a good situation for a new cinematographer.

Denis never questioned my speed at any time, for which I was grateful, though no doubt this was of concern to him with the ambitious schedule. However, he did suggest that he would be happy to operate the camera as well as direct, giving time for me to concentrate more on my lighting. Although I admit to having pangs of conscience about this, I gratefully accepted Denis’s generous offer; he had been a fine camera operator in his own right and was now making this gesture to ease my pain.

I am pleased to say that

Hot Target

finished on schedule and in the end my worries with the dreaded black set would not materialise. What did come from the exercise was the realisation that I would never be happy at the thought of combining the two positions of lighting cameraman and camera operator on a film – a dual role which later would sadly become the norm for many. As a result of this decision I would subsequently lose a number of films offered to me, but I would cling stubbornly to the principle that life was too short to let my artistic contribution suffer just to accommodate an accountant’s balance sheet.

Of course there are others who will disagree with this, suggesting I am old fashioned or that they prefer doing both jobs themselves, which again I consider to be a mistake for many reasons. With age fast creeping up and students eagerly waiting in the wings for their big opportunity, I doubt that today’s cinematographers will have a change of heart about this situation.

While I am in this controversial mood I would also say that I believe that camera assistants who have risen through the ranks on the studio floor and under a professional technician’s guidance probably make better camera operators than film-school students who are taught to operate the camera as well as light. Okay, perhaps I am old fashioned, for which I will not apologise, but there is much more to operating the camera than just looking through an eyepiece and keeping the actors in the frame.

Moving up the ladder would not come easily, nor would knowing that others would gain from any operating work I politely turned away, as those important contacts built up over the years gradually began to disappear. However, with

Biddy

,

On the Third Day

and now

Hot Target

added to the CV there could be no turning back.

Unfortunately, my move came at a time when the British film industry was experiencing another of its periodic slumps in film production. At times I wondered if Divine intervention was trying to tell me something, or possibly testing my courage in holding out. Although the odd titbit here and there would help my staying power it would not be enough to meet the demanding requirements of the British Society of Cinematographers, and I was hoping that one day I might win the right to add that valued BSC credit after my name.

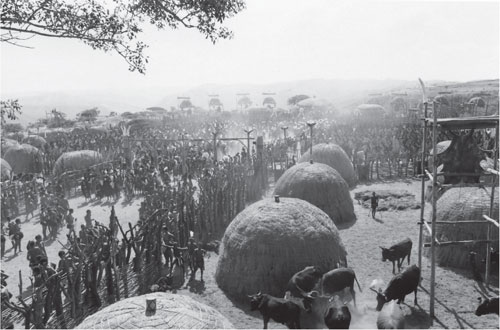

Filming Senzangakhona’s wedding on

Shaka Zulu

(1984). I wasn’t sure what was happening in the madness of it all, but somehow you came to accept it. The man with the red and white cap in the background is ‘Biza’, a white Zulu who grew up with Zulus and spoke the language like a native. He was our cultural expert, interpreter and later assistant director.

One thing that would help to address the problem would be an agent. If the word was to spread that ‘Alec Mills, director of cinematography’ was now available to the film world then possibly the dream would continue, provided that someone out there was willing to take a chance with me. Dreams or not, an agency soon called to say that they would like to represent me, which was strange when I had not spoken with anyone about this before – coincidence again? This would allow my puffed-up ego to exaggerate the importance of my three modest credits, with fingers crossed my man would be in a position to spread the word of my availability.

Although I was not expecting to be drowned in offers, the gentleman soon called back.

‘Alec, would you be interested working on a film in South Africa, and by the way does the name Shaka mean anything to you?’

No, was the simple answer to the second question. Shaka meant little or nothing to me. but when researching Shaka’s history it would seem way back in the 1820s the name alone spread fear among the Zulu nation. Suddenly I realised this could now be an exciting opportunity to work on a production that would help my career to move forward; at the same time I knew that it would require a big sacrifice from me to be working abroad. My heartbeat started to race as I tried to control the excitement of an agent showing an interest in me, while also knowing I would need to keep calm and play it down as if I was swimming in offers; obviously he knew differently – let’s face it, we are all actors playing our part in a scene.

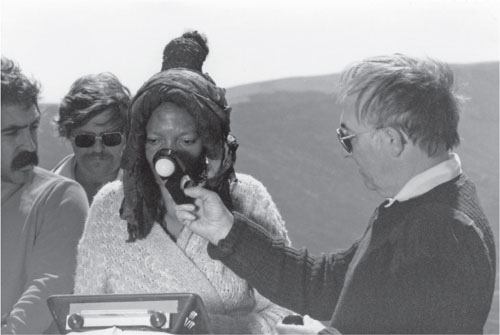

August 1984, Dundee, South Africa. Preparing for a scene with Nandi as she wanders in the wilderness with her illegitimate son, Shaka, and her daughter, Nunko, cast out from the Zulu tribe.

‘It’s a film/television series to be filmed in South Africa about a Zulu king – Shaka Zulu …’ Then there came an interminable pause when I thought we had been cut off before he decided to carry on. ‘… to be filmed in Zululand …’ Another long pause, still no response from me. Finally, with hesitation in his voice, he dropped the bombshell: ‘It will take a year to film!’

With that comment my heartbeat quickly returned to normal, knowing well I had no intention, wish or desire to leave my family behind for a year. My hesitation in answering his question was obvious to the caller who now realised that no cameraman could possibly be interested in leaving home for such a long time. Thanking him for his interest, I declined.

Thinking about this hasty decision later, I understood that as a new cinematographer looking for recognition I would need more lighting experience with more credits, which would surely come after a project like

Shaka Zulu.

If past experience had taught me anything, it was that opportunities like this do not come often, so perhaps this offer should not be rejected out of hand so easily. After discussing it with Suzy a suggestion was put to the production: I would be prepared to do six months filming on

Shaka Zulu

, with both parties keeping open an option with the second stage of filming. This idea was put to the director William Faure, who agreed and quickly became ‘Bill’.

The white men raising the British flag in Zululand. Edward Fox, playing Lieutenant Francis Farewell, is saluting in the foreground as Robert Powell, playing Dr Henry Fynn, looks on.

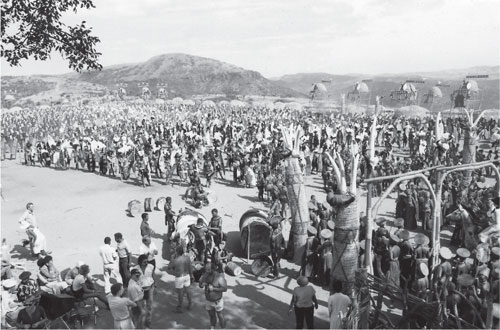

The entrance to Shaka’s capital, Bulawayo.

While I had now won my first film/television series as cinematographer, it meant the sacrifice of being abroad for a long time – out of sight and out of mind – possibly delaying any success or recognition here in the UK, which was always important to me. But if this was the only way forward then so be it: anything … anything to move my career forward.

Within days a large package arrived from Johannesburg containing fifteen scripts. Settling down to read each episode it soon became clear that I was involved with something big – possibly even spectacular.

Shaka Zulu

would hand me a photographic experience which would stay long in my memory throughout my entire career as a cinematographer, from which I would learn much with its many unforeseen challenges, not least with my first encounter of filming black actors – Nubian black! The scripts were written by an American, Joshua Sinclair, who had obviously researched the Zulu history in painstaking detail.

Shaka’s capital, Bulawayo. We were shooting with over 2,000 Zulu warriors for days.

Flying to Johannesburg would bring the sudden reality of the

Shaka

experience and the usual worries now started playing with my mind. Whether in heaven or hell, the legendary Zulu king would take his toll on me with the excitement of it all as my mood turned to one of anxiety as I started to think about the challenge ahead. The long flight gave me time to reflect on my apparent insanity, so that soon I had convinced myself that I had just made the biggest mistake of my life. Should there be anything of any comfort it was that I had managed to arrange for Frank Elliott, my trusted camera assistant, to join me later.