Shrinks (8 page)

Authors: Jeffrey A. Lieberman

Tags: #Psychology / Mental Health, #Psychology / History, #Medical / Neuroscience

If Freud was the CEO of the psychoanalytical movement, his management style was more like that of Steve Jobs than of Bill Gates. He wanted complete control of everything, and all designs needed to conform to his own sensibilities. As the society continued to grow and more new ideas were being proposed, the psychoanalytic CEO realized he needed to do something to gain tighter control over the movement and simultaneously bring his ideas to a larger audience. In the language of business, Freud wanted to expand his market share while retaining tight brand control.

He decided to dissolve the increasingly fractious Wednesday Psychological Society—which was still being held in his stuffy, overcrowded parlor—and reconstitute it as a formal professional organization. Only those who were fully committed to Freud’s ideas were invited to continue as members; Freud expelled the rest. On April 15, 1908, the new group introduced itself to the public as the Psychoanalytic Society. With just twenty-two members, the fledgling society held the promise of reshaping every inch of psychiatry and captivating the entire world—if it didn’t tear itself apart first.

Heretics

Though psychoanalytic theory was catching on and Freud was confident that his daring ideas about mental illness were fundamentally sound, he was quite conscious of the fact that he was on shaky ground with regard to scientific evidence. Rather than reacting to this lack of supporting data by conducting research to fill in the blanks, Freud instead made a decision that would seal the fate of psychoanalysis and critically affect the course of American psychiatry, fossilizing a promising and dynamic scientific theory into a petrified religion.

Freud chose to present his theory in a way that discouraged questioning and thwarted any efforts at verification or falsification. He demanded complete loyalty to his theory, and insisted that his disciples follow his clinical techniques without deviation. As the Psychoanalytic Society grew, the scientist who had once called for skeptical rigor in

A Project for a Scientific Psychology

now presented his hypotheses as articles of faith that must be adhered to with absolute fidelity.

As a psychiatrist who lived through many of the worst excesses of the psychoanalytic theocracy, I regard Freud’s fateful decision with sadness and regret. If we are practicing medicine, if we are pursuing science, if we are studying something as vertiginously complicated as the human mind, then we must always be prepared to humbly submit our ideas for replications and verification by others and to modify them as new evidence arises. What was especially disappointing about Freud’s insular strategy is that so many core elements of his theory ultimately proved to be accurate, even holding up in the light of contemporary neuroscience research. Freud’s theory of complementary and competing systems of cognition is basic to modern neuroscience, instantiated in leading neural models of vision, memory, motor control, decision making, and language. The idea, first promulgated by Freud, of progressive stages of mental development forms the cornerstone of the modern fields of developmental psychology and developmental neurobiology. To this day, we don’t have a better way of understanding self-defeating, narcissistic, passive-dependent, and passive-aggressive behavior patterns than what Freud proposed.

But along with prescient insights, Freud’s theories were also full of missteps, oversights, and outright howlers. We shake our heads now at his conviction that young boys want to marry their mothers and kill their fathers, while a girl’s natural sexual development drives her to want a penis of her own. As Justice Louis Brandeis so aptly declared, “Sunlight is the best disinfectant,” and it seems likely that many of Freud’s less credible conjectures would have been scrubbed away by the punctilious process of scientific inquiry if they had been treated as testable hypotheses rather than papal edicts.

Instead, anyone who criticized or modified Freud’s ideas was considered a blaspheming apostate, denounced as a mortal enemy of psychoanalysis, and excommunicated. The most influential founding member of the psychoanalytic movement, Alfred Adler, the man Freud once admiringly called “the only personality there,” was the first major figure to be expelled. Prior to meeting Freud, Adler had already laid out his own views on therapy, emphasizing the need to perceive the patient as a whole person and understand his whole story. In contrast to Freud’s theory of a divided consciousness, Adler believed the mind to be indivisible—an

Individuum

. Freud’s insistence on interpreting all of a patient’s conflicts as sexual in nature, no matter how improbable and far-fetched, also bothered Adler, since he felt that aggression was just as potent a source of psychic conflict.

But there may have been other reasons for their schism. When asked about acrimony among psychiatrists with an obvious reference to the members of the Wednesday Society, Freud replied, “It is not the scientific differences that are so important, it is usually some other kind of animosity, jealousy, or revenge, that gives the impulse to enmity. The scientific differences come later.” Freud was aloof, cold, with a laser-focused mind better suited for research than politics. Most of his patients were well-educated members of the upper strata of Viennese society, while the convivial Adler had greater affinity for the working class.

Like Stalin declaring Trotsky persona non grata, in 1911 Freud publicly declared Adler’s ideas contrary to the movement and issued an ultimatum to all members of the Psychoanalytic Society to drop Adler or face expulsion themselves. Freud accused Adler of having paranoid delusions and using “terrorist tactics” to undermine the psychoanalytic movement. He whispered to his friends that the revolt by Adler was that of “an abnormal individual driven mad by ambition.”

For his own part, Adler’s enmity toward Freud endured for the rest of his life. Whenever someone pointed out that he had been an early disciple of Freud, Adler would angrily whip out a time-faded postcard—his invitation to Freud’s first coffee klatch—as proof that Freud had initially sought his intellectual companionship, not the other way around. Not long before his death, in 1937, Adler was having dinner in a New York restaurant with the young Abraham Maslow, a psychologist who eventually achieved his own acclaim for the concept of self-actualization. Maslow casually asked Adler about his friendship with Freud. Adler exploded and proceeded to denounce Freud as a swindler and schemer.

Other exiles and defections followed, including that of Wilhelm Stekel, the man who originally came up with the idea for the Wednesday Psychological Society, and Otto Rank, whom Freud for years had called his “loyal helper and co-worker.” But the unkindest cut of all, in Freud’s eyes, undoubtedly came from the Swiss physician Carl Gustav Jung, his own Brutus.

In 1906, after reading Jung’s psychoanalysis-influenced book

Studies in Word-Association

, Freud eagerly invited him to his home in Vienna. The two men, nineteen years apart, immediately recognized each other as kindred spirits. They talked for thirteen hours straight, history not recording whether they paused for food or bathroom breaks. Shortly thereafter, Freud sent a collection of his latest published essays to Jung in Zurich, marking the beginning of an intense correspondence and collaboration that lasted six years. Jung was elected the first president of the International Psychoanalytical Association with Freud’s enthusiastic support, and Freud eventually anointed Jung as “his adopted eldest son, his crown prince and successor.” But—as with Freud and Adler—the seeds of discord were present in their relationship from the very start.

Jung was deeply spiritual, and his ideas veered toward the mystical. He believed in synchronicity, the idea that apparent coincidences in life—such as the sun streaming through the clouds as you emerge from church after your wedding—were cosmically orchestrated. Jung downplayed the importance of sexual conflicts and instead focused on the quasi-numinous role of the

collective unconscious

—a part of the unconscious, according to Jung, that contains memories and ideas that belong to our entire species.

Freud, in sharp contrast, was an atheist and didn’t believe that spirituality or the occult should be connected with psychoanalysis in any way. He claimed to have never experienced any “religious feelings,” let alone the mystical feelings that Jung professed. And of course, in Freud’s eyes, sexual conflict was the sina qua non of psychoanalysis.

Freud became increasingly concerned that Jung’s endorsement of unscientific ideas would harm the movement (ironic, as there were no plans to develop scientific support for Freud’s ideas either). Finally, in November of 1912, Jung and Freud met for the last time at a gathering of Freud’s inner circle in Munich. Over lunch, the group was discussing a recent psychoanalytic paper about the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep. Jung commented that too much had been made of the fact that Amenhotep had ordered his father’s name erased from all inscriptions. Freud took this personally, denouncing Jung for leaving Freud’s name off his recent publications, working himself into such a frenzy that he fell to the floor in a dead faint. Not long after, the two colleagues parted ways for good, Jung abandoning psychoanalytic theory entirely for his own form of psychiatry, which he called, with an obvious debt to Freud, “analytical psychology.”

Despite the tensions within the fracturing psychoanalytic movement, by 1910 psychoanalysis had become the

traitement du jour

in continental Europe and established itself as one of the most popular forms of therapy among the upper and middle classes, especially among affluent Jews. Psychoanalytic theory also became highly influential in the arts, shaping the work of novelists, painters, and playwrights. But although by 1920 every educated European had heard of Freud, psychoanalysis never wholly dominated European psychiatry. Even at its high-water mark in Europe, psychoanalysis competed with several other approaches to mental illness, including Gestalt theory, phenomenological psychiatry, and social psychiatry, while in the United States, psychoanalysis failed to gain any traction at all.

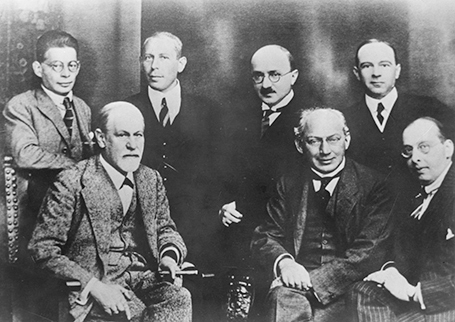

Sigmund Freud’s inner circle of the Psychoanalytic Society. From left to right are Otto Rank, Freud, Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, Sándor Ferenczi, Ernest Jones, Hanns Sachs. (HIP/Art Resource, NY)

Then, in the late 1930s, a sudden twist of history obliterated psychoanalysis from the face of continental Europe. After the rise of the Nazis, Freud and his theory would never regain their standing on the Continent they had enjoyed in the early decades of the twentieth century. At the same time, the chain of events initiated by German fascism roused psychoanalysis from its American slumber and invigorated a new Freudian force in North America that would systematically take over every institution of American psychiatry—and soon beget the shrink.

A Plague upon America

While nineteenth-century European psychiatry oscillated like a metronome between psychodynamic and biological theories, before the arrival of Freud there was precious little that could be mistaken for progress in American psychiatry. American medicine had benefited, by varying degrees, from advances in surgery, vaccines, antiseptic principles, nursing, and germ theory coming from European medical schools, but the medicine of mental health remained in hibernation.

The origins of American psychiatry are traditionally traced to Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. He is considered a Founding Father of the United States, and through the sepia mists of time he has acquired another paternal appellation: Father of American Psychiatry. Rush was considered the “New World” Pinel for advocating that mental illness and addictions were medical illnesses, not moral failings, and for unshackling the inmates of the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1780.

However, while Rush did publish the first textbook on mental illness in the United States, the 1812 tome

Medical Inquiries and Observations upon the Diseases of the Mind

, he did not encourage or pursue experimentation and evidence-gathering to support his thesis and organized his descriptions of mental illness around theories he found personally compelling. Rush believed, for instance, that many mental illnesses were caused by the disruption of blood circulation. (It is interesting to observe that before the advent of modern neuroscience so many psychiatrists envisioned mental illness as some variant of a clogged sewage pipe, with disorders arising from the obstructed flow of some essential biological medium: Mesmer’s magnetic channels, Reich’s orgone energy, Rush’s blood circulation.)

To improve circulation to the mentally ill brain, Rush treated patients with a special device of his own invention: the Rotational Chair. The base of the chair was connected to an iron axle that could be rotated rapidly by means of a hand crank. A psychotic patient would be strapped snugly into the chair and then spun around and around like an amusement park Tilt-A-Whirl until his psychotic symptoms were blotted out by dizziness, disorientation, and vomiting.